|

Ocmulgee Mounds and Earth Lodge 9,000 BC

Ocmulgee National Monument Macon Georgia

Some of the largest Indian Mounds in the state of Georgia, the Ocmulgee Mounds on the Macon Plateau are a significant part

of Georgia history. Built during the Early Mississippian Period, the mounds were the centerpiece of a culture known as the

Moundbuilders.

Moundbuilder history

Archaic Moundbuilders may have developed in Louisiana, spreading north to inhabit the rich valleys of the Mississippi and

its tributaries, and following other coastal rivers inland. Around 1000 BC the first mounds appeared in the present-day state

of Georgia. These mounds, some of which were located on the Macon Plateau, were similar in many ways to mounds built in other

places throughout the Eastern United States.

Near the Ohio River two distinct cultures of Moundbuilders arose, first the Adena (400? BC) and then the Hopewell (100 BC).

By 500 AD, the Hopewell appear to have been in decline. From the west came the Mississippians, in about 900 AD. Some Georgia

mounds, especially Kolomoki, exhibit traits of both civilizations.

The Mississippians

Built on a complex socio-political structure with advanced agricultural techniques, including perhaps crop rotation, the Mississippian

culture spread throughout much of the Eastern United States. They used waterways as a major form of transportation, and had

an extensive trading network.

Moundbuilders at Ocmulgee

Between 900 and 950 AD the mounds at Ocmulgee were constructed. Over the next 300 years the Moundbuilders inhabited this site,

considered to be the largest village in the Southeast. During this time period the Great Temple Mound was constructed, along

with the other lesser mounds and earth lodges nearby. By the end of the Early Mississipian Era (1200 AD) the mounds at Ocmulgee

were in decline, while the Etowah Indian Mounds were flourishing.

Then, sometime after 1300AD a second culture, known as the Lamar culture, began to flourish near the Ocmulgee mounds. This

site, not far from the Ocmulgee Mounds and within the same National Park area features a unique "spiral" mound, funeral mound,

and other small mounds. The Lamar Culture spread throughout the Southeast and had contact with non-Moundbuilder tribes such

as the Cherokee.

The Ocmulgee Indian Mounds history

First mention of the mounds is by a member of James Oglethorpe's Georgia Guard who saw the mounds on a trip with Oglethorpe

to the Creek capital of Coweta. Naturalist William Bartram noted Ocmulgee on both his visits to the site during the 1770's,

calling them the "Oakmulgee fields". The mounds remained in Creek hands well into the 19th century, and were exempted from

a treaty ceding the surrounding area. The mounds, however, were finally ceded to the state and distributed to settlers (1828).

Macon's rapid expansion during the 1800's compromised the mounds with incursions to build railroad lines and public works

projects. By 1930 the mounds had been heavily damaged. A group of concerned citizens and the Smithsonian Institute organized

an excavation of the Ocmulgee Indian Mounds to prove their archeological value. Noted archeologist Dr. A. R. Kelly led the

expedition. Based on Kelly's finds, the Ocmulgee National Park was created in 1936.

Today the park continues to grow thanks to donations of nearby land. It struggles to maintain the land as intact as possible

not only for this generation but for future generations as well.

OCMULGEE CHRONOLOGY

pre-9,000 BC Paleo Indian Period

Ice Age hunters arrive in the Southeast, leaving one of their distinctive "Clovis" spear points on the Macon Plateau (in the

1930's this became the first such artifact found in situ in the southern U.S.).

8,000-9,000 BC Transitional Period

People adjust to gradually warming weather as the glaciers melt and many Ice Age mammals become extinct.

1,000-8,000 BC Archaic Period

Efficient hunting/gathering; adaptation to a climate much like today; use of the atlatl (spear thrower), woodworking tools,

etc.; white-tail deer becomes a staple; extensive shell mounds along the coast and some inland rivers.

2,500 BC First pottery in this country appears along the Georgia/South Carolina coast and

soon filters into what is now Middle Georgia; it is tempered or strengthened with plant fibers which burn out during firing,

giving a worm-hole appearance to the vessel surface.

1,000 BC-AD 900 Woodland Period

Pottery tempered with sand and grit, sometimes decorated with elaborate designs incised, punctated or stamped into its surface

before firing; cultivation of sunflowers, gourds, and several other plants; construction of semi-permanent villages; stone

effigy mounds and earthen burial and platform mounds; connections to the Adena/Hopewell Cultures farther North and to Weeden

Island in Florida and South Georgia.

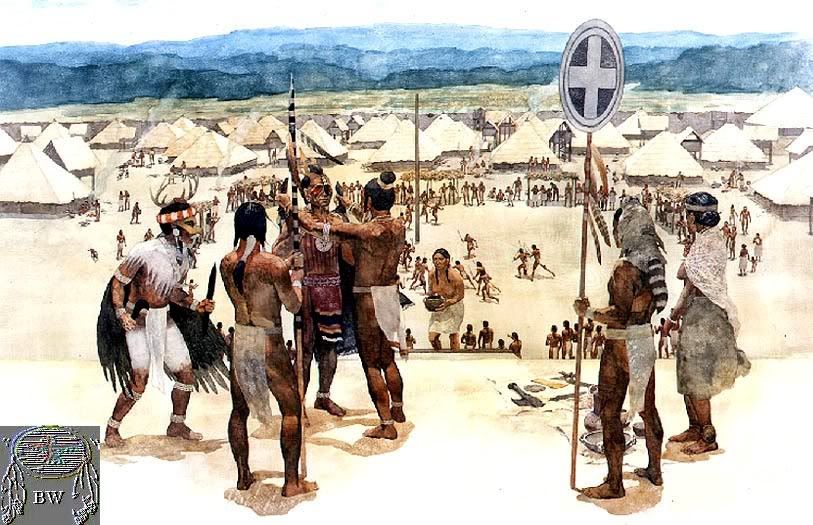

A.D. 900-1150 Early Mississippian Period

A new way of life, believed to have originated in the Mississippi River area appears on the Macon Plateau. These people,

whose pottery is different from that made by the Woodland cultures in the area, construct a large ceremonial center with huge

earthen temple / burial / domiciliary mounds and earthlodges, which serve as formal council chambers. Their economy is supported

by agriculture, with corn, beans, squash and other crops planted in the rich river floodplain. Indigenous Woodland people

in surrounding areas interact with these people, who possess early symbols and artifacts associated with the Southeastern

Ceremonial Complex (Southern Cult).

1150-1350 Mature Mississippian Period

The great Macon Plateau town declines and the Lamar and Stubbs Mounds and Villages appear just downstream. These towns are

a combination of the old Woodland culture and Mississippian ideas. The Southern Cult, distinguished by flamboyant artistic

motifs and specialized artifacts, flourishes at places like Roods Landing and Etowah (GA), Moundville (AL), Hiwasee Island

(TN), Cahokia (IL), and Spiro (OK).

1350-1650 Late Mississippian Period (Protohistoric)

The Lamar Culture, named for the Lamar Mounds and Village Unit of Ocmulgee National Monument, becomes widespread in the Southeast;

chiefdoms marked by smaller, more numerous, often stockaded villages with a ceremonial center marked by one or two mounds;

combination of the both Woodland and Mississippian elements.

1540 Chroniclers of Hernando DeSoto's expedition into the interior of North America write the first descriptions

of the Lamar and related cultures, ancestors of the historic Creek (Muscogean), Cherokee (Iroquoian), Yuchi (Euchee), and

other Southeastern people. Most of their main towns are situated near rich river bottomland fields of corn, beans and squash.

Many towns feature open plazas and earthen temple mounds. Public buildings and homes are constructed of upright logs, interwoven

with vines or cane and plastered with clay (wattle and daub). Some are elaborately decorated and contain large woodcarvings.

DeSoto’s expedition’s 600 men and 300 horses devastate local food supplies; epidemics of European diseases decimate

many populations.

1565 The Spanish establish their first permanent settlement at St. Augustine, set up outposts at towns along the Atlantic

coast to the North, and begin to missionize the Indians. Priests and soldiers travel up the river systems to other towns

in the interior of the area which would become Georgia.

1670 The British establish Charles Town (Charleston, SC) on the Atlantic coast. Despite Spanish opposition, English

explorers initiate contact and trade with towns in the interior.

1690 A British trading post is constructed on Ochese Creek (present Ocmulgee River at the site now protected within

Ocmulgee National Monument). A number of Muscogee towns move from the Chattahoochee River to this vicinity to be near the

English. At this time, the Ocmulgee river is called Ochese-hatchee or Ochisi-hatchi (various spellings). The towns are known

as the Ochese Creek Nation. The British eventually refer to them simply as the "Creeks." They speak variations of the Muscogean

language, but their confederacy incorporates other groups, such as the Yuchi, who speak different languages. The Creeks acquire

horses from Spanish Florida and guns from the British. Their culture and dress is modified by use of trade goods such as

iron pots, steel knives, and cotton cloth.

1704 Col. James Moore, with a band of some fifty men from Charles Town, leads 1,000 warriors from the Creek towns on

the Ocmulgee River to Florida. They devastate the Spanish Apalachee Mission system and drive the Spaniards back to St. Augustine.

After many of the inhabitants of northern Florida are exterminated, some of the Creeks move into the area and incorporate

the survivors into their own group. These people are subsequently known as the Seminole and Miccosuki.

1715 The Yamassee War erupts in protest against British indignities related to the fur trade, including the taking of

Indian shipped as slaves to work in Carribean sugar plantations. Many traders in Indian territory are killed. In retaliation,

the British burn Ocmulgee Town on Ochese Creek. The Creek towns withdraw to the Chattahoochee River and the Yuchis move with

them. The people are known as the Lower Creeks. The Upper Creeks are centered on the Coosa and Tallapoosa Rivers to the northeast.

1733 The Georgia Colony settles on lands along the banks of the Savannah River given to General James Oglethorpe by

Chief Tomochichi of the Yamacraws, a group related to the Lower Creeks. The Colony serves as a buffer between South Carolina

and Spanish Florida.

1739 General James Oglethorpe, founder of the Georgia Colony, travels the ancient trading path through the mounds and

old planting fields at Ocmulgee enroute to Coweta (near what is now Columbus, GA) to meet with the Creeks. One of his Rangers

writes a short description of the mounds at what is now Ocmulgee National Monument. A western boundary for the colony is

defined along the Ogeechee River. The area extends along the coast to the present northern border of Florida.

1774 William Bartram, reknown naturalist and botanist, follows the Lower Creek Trading Path from Augusta

through the area. In his journal, he records this account of the Ocmulgee Old Fields:

"On the heights of these low grounds are yet visible

monuments, or traces, of an ancient town, such as artificial

mounts or terraces, squares and banks, encircling considerable

areas. Their old fields and planting land extend up and down

the river, fifteen or twenty miles from this site. If we are to

give credit to the account the Creeks give of themselves, this

place is remarkable for being the first town or settlement, when

they sat down (as they term it) or established themselves, after

their emigration from the west..."

1778 During the Revolutionary War, many Creeks want to remain neutral, but Alexander McGillivray (of Creek-Scottish

descent,educated in South Carolina, Principal Chief of both the Upper and Lower Creeks) leads them into an alliance with England.

1793 Invention of the cotton gin greatly accelerates the desire for rich river bottomland. Creek Indians, most

of them excellent farmers, quickly adapt to a cotton-based economy.

1805 The first Treaty of Washington cedes the remainder of the land between the Oconee and Ocmulgee Rivers, excluding

a 3x5-mile strip known as the Old Ocmulgee Fields Reserve at present Macon, which the Muscogee (Creek) people refuse to give

up. The treaty allows the United states to construct a road across the Creek Nation to the Alabama River and facilities for

public accomodations along this road. Much of this "Federal Road" follows the ancient Lower Creek Trading Path and eventually

stretches from Washington, D.C. to New Orleans. The treaty also provides for a United States military fort on the

Reserve to guard the frontier along the Ocmulgee River. This outpost is called Fort Hawkins in honor of Benjamin Hawkins,

U.S. Indian Agent to the Creeks and friend of George Washington.

1806 Fort Hawkins is built a short distance from the mounds. It serves as a frontier outpost, trading and center

and location for treaty payments to the Creeks until the United States boundary is later extended to Alabama Territory. For

the entirety of its existence as a U.S. military fort, it sat on land owned by the Muscogee (Creek) Confederacy.

1811 Shawnee Chief Tecumseh, working with his brother the Prophet, travels up and down the frontier exhorting the

Native Americans to discard their plows, whiskey and the white man’s ways. Some of the Creeks join his movement and

nearly every town has a so-called "Red Stick" faction. The leaders are as divided as their people. William McIntosh emerges

as leader of the faction loyal to the U.S. government. William Weatherford (Red Eagle) becomes the most important leader

of the Red Sticks.

1812 General Andrew Jackson (later President) stops at Fort Hawkins during the War of 1812. The fort is an important

port of rendezvous for dispatching troops. This war with Great Britain concerns the issues of neutral maritime rights and

British involvement in Native American problems along the frontier. Hostilities between Creek loyalists and traditionalist

Red Sticks increase. Red Sticks attack and destroy Tuckabatchee and several other Upper Creek towns in northern Alabama.

1819 The ancient Lower Creek Trading Path, now called the Federal Road, is the major artery from North to Southwest

for many years (State Highway 49 follows much of this route through Central Georgia). It serves as the postal route from

New York to New Orleans. A ferry is built near the mounds on the Old Ocmulgee Fields Reserve, and the first white child,

later Mrs. Isaac Winship, is born in the area.

1821 The Creeks give up the lands between the Ocmulgee River and the Flint River.

1823 The Creek Council passes a law providing the death penalty for anyone ceding land without the authority of

the Council. Pressures for Indian removal continue to increase. Some Creeks, including William McIntosh, believe removal

is inevitable.

The City of Macon is laid out across the river from Fort Hawkins. The first newspaper in Middle Georgia, the Georgia Messenger,

is published at Fort Hawkins, and a post office is established.

1825 The Treaty of Indian Springs ceding the last Creek lands in Georgia is signed by Chief William McIntosh.

His cousin is the governor of Georgia. He sells the Creek lands and is consequently assassinated by his own people. The

treaty is declared illegal by the federal government, but Georgia authorities disagree. They press harder for removal.

1826 The second Treaty of Washington officially surrenders the last Creek lands in Georgia. Some of the Creeks

join the Seminole in Florida, others move into Alabama. About 1,300, mostly members of the McIntosh faction, resettle to

the valley of the Arkansas River in "Native American Territory," now the state of Oklahoma, on lands given to them under the

government’s voluntary removal program

1828 The Old Ocmulgee Fields Reserve, including Fort Hawkins and the mounds, is surveyed and laid off into land

lots incorporated into the city of Macon. Roger and Eliazar McCall purchase a portion of the Old Fields and establish a successful

flatboat manufacturing enterprise. Of the mound area, the local newspaper reported:

"The site is romantic in the extreme; that, with the burial

mounds adjacent, have long been favorite haunts of our

village beaux and belles, and objects of curiosity to strangers.

We should regret to see these monuments of antiquity and of

our history levelled by the sordid plow - - we could wish that

they might always remain as present, sacred to solitude, to

reflection and inspiration."

1836 The Creek War of 1836 ends when about 2,500 people, including several hundred warriors in chains, are marched

on foot to Montgomery, AL, and crowded onto barges during the extreme heat of July. They are carried by steamboats down the

Alabama River, beginning their forced removal to Indian Territory. During the summer and winter of 1836-early 1837, over

14,000 Creeks make the three-month journey to Oklahoma, a trip of over 800 land miles and another 400 by water. Most leave

with only what they can carry.

1839 The Cherokee begin their "Trail of Tears." A few escape and remain in the mountains of East Tennessee and

North Carolina where most of their descendants now live on the Qualla Reserve around Cherokee, NC.

1843 The Central Railroad constructs a railroad line into Macon through the Ocmulgee Old Fields destroying a portion

of the Lesser Temple Mound and the great prehistoric town. A locomotive "roundhouse" is located near the Funeral Mound.

1840 The huge oak trees on the mounds are cut for timber. Until this time, the Old Ocmulgee Fields and Brown’s

Mount (another scenic prehistoric town about 6 miles down river) had been favorite resorts for picnics and parties, first

by the officers at Fort Hawkins then by the residents of Macon.

Much of the Macon Plateau site becomes part of the Dunlap Plantation. Clay for brick manufacturing is mined near the Great

Temple Mound and a fertilizer factor is constructed nearby.

1864 Union General George Stoneman nears the city of Macon in July. Governor Brown, who is in Macon, calls for every

able-bodied Man to defend the city. A battery is stationed near the site of Fort Hawkins. Big guns are loaded on flatcars

at the railroad bridge

over the Ocmulgee River inside the boundary of what is now the Ocmulgee National Monument. Gen. Stoneman destroys Griswoldville,

continues to Macon and burns the railroad bridge over Walnut Creek on the Dunlap property. He uses the Dunlap's farm house

as his headquarters during the ensuing battle. Failing to take the city, Stoneman and his troops are pursued into nearby

Jones County, where they are defeated at Sunshine Church. General Stoneman and his officers are incarcerated at Camp Oglethorpe

in Macon and his enlisted men are sent to the infamous prisoner of war camp at Andersonville. Stoneman is the highest ranking

Union officer taken prisoner during the Civil War.

1874 A second huge cut for a railroad (still in use) is excavated through the mound area and destroys a large portion

of the Funeral Mound. According to Charles C. Jones, in his book, Antiquities of the Southern Indians, many relics and human

burials are removed during this work.

1933 A large portion of McDougal Mound is removed to use as fill dirt for Main Street. Motorcycle hill-climbing

leaves scars on the slopes and summit of the Great Temple Mound. A group of local citizens are convinced that the mounds

are of great historical significance and should be preserved. Led by General Walter A.Harris, Dr. Charles C. Harrold, and

Linton Solomon, they seek assistance from the Smithsonian Institution, which sends Dr. Arthur Kelly to organize and conduct

archeological excavations on the Macon Plateau.

1934 Archeological treasures are unearthed. As the work progresses, a bill is passed by Congress to authorize establishment

of a 2,000-acre Ocmulgee National Park. The archeological effort is largest excavation ever, until this time, undertaken

in the country. Labor is provided by hundreds of workers employed under several Great Depression-era public works programs.

1936 President Franklin D. Roosevelt on December 12th signs the Proclamation establishing Ocmulgee National Monument

and directing the National Park Service to preserve and protect 2,000 acres of "lands commonly known as the Old Ocmulgee Fields..."

Due to economic constraints, only 678.48 are acquired, including 40 acres at the detached Lamar Mounds and Village. Later,

an additional 5 acres are added to the Lamar Mounds and Village Unit and the parcel known as Drakes Field is donated to the

nation for inclusion in Ocmulgee National Monument by the City of Macon. The park presently encompasses 702 acres.

1940 Great Depression Relief-era crewmen, including members of Civilian Conservation Corps Company 1426 stationed

at Ocmulgee National Monument, are drafted into military service as the United States enters World War II. Man are sent to

nearby Camp Wheeler which becomes the largest infantry training camp in the nation.

1960's An interstate highway (I-16), constructed through the Macon Plateau Unit, cuts the primary visitor use area

off from the park's mile-long river boundary and causes significant hydrological changes to lands located in the river floodplain.

During archeological excavation within the highway corridor inside the park, evidence of Muscogee (Creek) and earlier settlement,

along with three human burials, are discovered. A number of important prehistoric and historic sites outside the park are

destroyed or heavily damaged, including the nearby Gledhill I, II and III (where an Ice Age Clovis spearpoint is found by

an artifact collector during removal of fill dirt for road construction), along with the New Pond site, Adkins mound, and

Shellrock Cave. Archaic, Woodland, Mississippian and historic Creek villages and campsites across the river, such as Mile

Track, Napier, Mossy Oak and Horseshoe Bend, are already damaged by levee construction in the 1940's.

1970's The Swift Creek Mounds and Village, type-site for a widespread Woodland Period culture, is destroyed for construction

of a Bibb County Sheriff's Department firing range. Dr. Kelly's early archeological collections, still under the care of

the National Park Service, are all that remain of this large site, which was located on the Ocmulgee Old Fields near the Lamar

Village Unit of Ocmulgee National Monument.

1992 Descendants of Roger and Eliazar McCall donate almost 300 acres, adjoining the park's Walnut Creek boundary,

to the National Park Service. The Archeological Conservancy accepts ownership pending legislation to incorporate it into

Ocmulgee National Monument. The land, owned by this family for almost 175 years, has been designated the Scott-McCall Archeological

Preserve.

1997 The Old Ocmulgee Fields are determined eligible to become the first National Register of Historic Places listing

for a Traditional Cultural Property, or District, east of the Mississippi River. This distinction recognizes the area's great

significance to the Muscogee (Creek) people.

Present The park's staff, the OcmulgeeNational Monument Association, the Friends of Ocmulgee Old Fields, and the

park's many volunteers remain dedicated to the mission of protecting and preserving this very special place for the enjoyment

of today's citizens and future generations.

http://www.nps.gov/ocmu/index.htm

LINK TO BRAVEHORSE WARRIORS VOLUME TWO

|