|

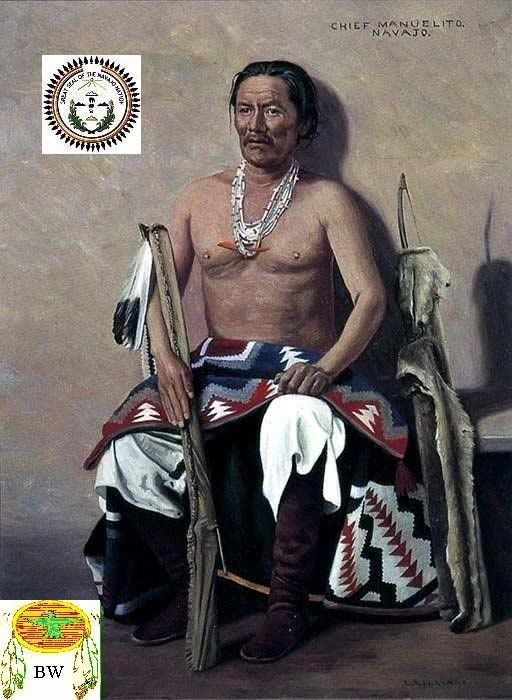

Manuelito

(1818-1894)

Warriors Citation

Born into the Bit'ahni (Folded Arms People) clan near Bear Ears Peak in southeastern Utah about 1818, Manuelito was not well

known until he was elected headman after the death of Zarcillas Largas (Long Earrings). He was a noted warrior and married

the war chief Narbona's daughter. Later, he took a second wife after a raid on a Mexican settlement. Manuelito is spanish

for "Little Manuel". His Navajo names included Hastin Ch'ilhajinii or Childjajin, meaning "The man of the Black Weeds"; Ashkii

Dighin, or "Holy Boy", which he was called as a youth; and Haskeh Naabah, or "The Angry Warrior," his war name. At the beginning

of the Mexican war in 1846, the United States quickly occupied New Mexico. To punish the Navajo for stealing lifestock, Colonel

Alexander W. Doniphan led his Missouri volunteers into the Navajo Homelands. Since each Navajo headman was responsible only

for the acts of members of his group and there were no centralized head chiefs, there was much misunderstanding between the

Navajos and the whites. Hiding in their rugged terrain, and particularly in the recesses of their sacred place, Canyon de

Chelly, the Navajos avoided any major military conflicts with the Americans. In 1846 and 1849, Navajo headmen negotiated treaties

with the American government, but they avoided U.S. control. During the 1850's, Navajo leaders such as Manuelito had become

wealthy through agricultural pursuits, livestock raising, and raids. But disputes emerged over grazing rights at the mouth

of Canyon Bonito near Fort Defiance between the Navajos and the U.S. soldiers. Although the Navajos had grazed their livestock

for generations on this land, the army wanted it as a pasture for its horses. The Americans killed some Navajo horses; the

Navajos took army horses to compensate for their lost mounts. At this point, Zarcillas Largas stepped down as a headman, stating

that he could no longer command the respect of his men, and Manuelito was elected as the new headman. In 1859, as a consequence

of the continuing unease, Manuelito's home, crops, and livestock were destroyed by U.S. soldiers in a punishment raid for

his people's past transgressions. In 1860, Manuelito and Barboncito retaliated in an attack on Fort Definace.

Although the Navajos came very close to capturing it, they were driven back in a valiant defense by the Americans. Colonel

Edward R. S. Canby unsuccessfully pursued the Navajos into the Chuska Mountains; Manuelito and his warriors used guerrilla

tactics to wear Canby down. In January 1861, Manuelito, Barboncito, Herrero Grande, Delgadito, and Armijo met with Canby at

Fort Fauntleroy (later Fort Wingate) to diskuss peaceful solutions. During this period, Herrero Grande was made principal

chief and spokesman of all Navajo bands. Over the next few years, tensions remained high in New Mexico. In September 1861,

fighting broke out over a horse race at Fort Fauntleroy. Navajos claimed that a soldier had cheated them by cutting Manuelito's

bridle rein; officials decided to cancel the race. In 1862, Union troops drove the last of the Confederate troops out of New

Mexico. In 1863, General James Henry Carleton became the new commander of the Department of New Mexico and made Colonel Christopher

"Kit" Carson his field commander with orders to confine all Indians to a reservation at Fort Sumner, New Mexico (a desolate

area also called Bosque Redondo). When the Navajos refused the order to surrender, Carson and his troops began to destroy

their homes, livestock and crops. The devastation was enormous, and the Navajo chiefs began to surrender in the fall of 1863,

beginning with Delgadito in October. Shrewdly, Carleton supplied Delgadito well for the 350-mile trek to Fort Sumner. Delgadito

then returned and persuaded other chiefs to follow on the Long Walk. By spring 1864, Navajos were surrendering by the thousands,

but Manuelito held out. In February 1865, Carleton told Manuelito to surrender forthe sake of his starving people, but Manuelito

said no, and stated, "I have nothing to lose but my life, and they can come and take that whenever they please. ...If I am

killed innocent blood will be shed." Finally, in September 1866, he and his twenty-three remaining men laid down their arms;

they were starving and in rags. The plight of the Navajos at Fort Sumner was no better. While over two hundred Navajos had

died on the Long Walk to Fort Sumner in the barren flats of the Pecos River, the survivors at Bosque Redondo fared even worse.

With no food and clothing, over two thousand men, women, and children died of disease and starvation. Carleton's policies

were deemed excessive by his superiors and he was relieved of his command. On June 1, 1868, the Navajos agreed to a treaty

granting them 3.5 million acres and returning them to their homeland adjacent to Fort Defiance. From 1870 through 1884, Manuelito

served as head chief of the Navajos. In 1872, Manuelito was also elected head of the Indian police force. Although Henry Chee

Dodge succeeded him as principal chief in 1885, Manuelito continued to be a strong force among the Navajos. When he died in

1894 at the age of seventy-five, he was one of the most respected people in Navajo history. From: historical accounts & records

LINK TO BRAVEHORSE WARRIORS VOLUME TWO

|