|

King Montezuma

(1466-1520)

Warriors Citation

Aztec ruler ("huey tlatoani" of Tenochtitlan), leader of the Aztec Triple Alliance from c. 1502–1520. He is known for

being the ruler of the Aztec empire at the beginning of the Spanish conquest of Mexico. The portrayal of Montezuma in history

has mostly been colored by his role as ruler of a defeated nation, and many sources describe him as weak-willed and indecisive.

The general biases of the historical sources make it difficult to ascertain anything definitive about his role during the

Spanish invasion, and this has led to some controversy as to how to most accurately portray him. Recently historians have

pointed to Montezuma’s many architectural, scientific, military and spiritual projects as evidence of a strong and industrious

ruler. The descriptions of the life of Montezuma are full of contradictions, and thus nothing is known for certain about his

personality and rule. These contradictions are apparently the result of various biases. Spanish conquistadors such as Bernal

Diaz del Castillo and Hernan Cortés depict Montezuma as a harsh and fickle-minded ruler, perhaps attempting to justify deposing

him in humanitarian terms. The Florentine Codex, made by Bernardino de Sahagún and his native informants of Tenochtitlan-subjugated

Tlatelolco, generally portrays Tlatelolco and Tlatelolcan rulers in a favorable light relative to the Tenocha, and Montezuma

in particular is depicted unfavorably as a weak-willed, superstitious and indulgent ruler.(Restall 2003) Historian James Lockhart

suggests that the people needed to have a scapegoat for the Aztec defeat, and Montezuma naturally fell into that role. Romero

Vargas Iturbide's study entitled "Montezuma the Magnificent" criticized the accounts of Bernal Diaz del Castillo and Hernan

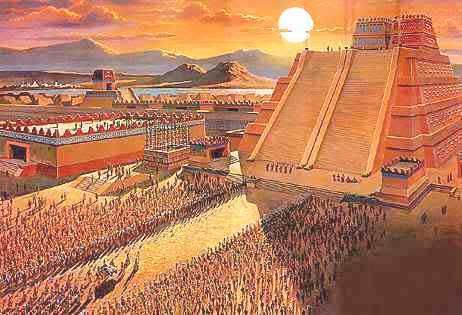

Cortes as biased while highlighting Montezuma’s virtues. As Aztec ruler, he expanded the Aztec Empire the most; warfare

expanded the territory as far south as Xoconosco in Chiapas and the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. He elaborated the Templo Mayor

and revolutionized the tribute system. He also increased Tenochtitlán's power over its allied cities to a dominant position

in the Aztec Triple Alliance. He created a special temple, dedicated to the gods of the conquered towns, inside the temple

of Huitzilopochtli. He also built a monument dedicated to the Tlatoani Tízoc. In another tale, when Montezuma took some corn

from a field, an angry peasant reminded him that he was forbidden to do so. Surprised by this, Montezuma decided to elevate

the macechualli to a higher rank. The treatment he gave to the commoner in this case contrasts with the prohibitions he imposed

on the pipeline (upper classes). Some of the Aztec stories about Montezuma describe him as being fearful of the Spanish newcomers,

and some sources, such as the Florentine codex, comment that the Aztecs believed the Spaniards to be gods and Cortés to be

the returned god Quetzalcoatl. The veracity of this belief is inordinately difficult to ascertain, and sometimes regarded

as apocryphal (Restall 2003). Much of the idea of Cortés being seen as a deity can be traced back to the Florentine Codex

written down some 50 years after the conquest. In the codex' description of the first meeting between Montezuma and Cortés,

the Aztec ruler is described as giving a prepared speech in classical oratorical Nahuatl, a speech which as described verbatim

in the codex (written by Sahagún's Tlatelolcan informants who were probably not eyewitnesses of the meeting) included such

prostrate declarations of divine or near-divine admiration as, "You have graciously come on earth, you have graciously approached

your water, your high place of Mexico, you have come down to your mat, your throne, which I have briefly kept for you, I who

used to keep it for you," and, "You have graciously arrived, you have known pain, you have known weariness, now come on earth,

take your rest, enter into your palace, rest your limbs; may our lords come on earth." Subtleties in, and an imperfect scholarly

understanding of, high Nahuatl rhetorical style make the exact intent of these comments tricky to ascertain, but Restall argues

that Montezuma politely offering his throne to Cortés (if indeed he did ever give the speech as reported) may well have been

meant as the exactly opposite of what it was taken to mean: politeness in Aztec culture was a way to assert dominance and

show superiority. This speech, which has been widely referred to, has been a factor in the widespread belief that Montezuma

was addressing Cortés as the returning god Quetzalcoatl. Other parties have also propagated the idea that the Native Americans

believed the conquistadors to be gods: most notably the historians of the Franciscan order such as Fray Geronimo Mendota (Martínez

1980). Some Franciscans at this time held millenarian beliefs (Phelan 1956) and the natives taking the Spanish conquerors

for gods was an idea that went well with this theology.

Bernardino de Sahagún, who compiled the Florentine Codex, was also a Franciscan. Bernardino de Sahagún (1499-1590) mentions

eight events, occurring prior to the arrival of the Spanish, which were interpreted as signs of a possible disaster, e.g.

a comet, the burning of a temple, a crying ghostly woman, and others. Some speculate that the Aztecs were particularly susceptible

to such ideas of doom and disaster because the particular year in which the Spanish arrived coincided with a "tying of years"

ceremony at the end of a 52-year cycle in the Aztec calendar, which in Aztec belief was linked to changes, rebirth and dangerous

events. An account by Fernando Alvarado Tezozómoc (1598) records a story of how Montezuma sent emissaries to find the legendary

wizard and prophet, Huemac, who, according to legend, had predicted the arriving of Quetzalcoatl one thousand years before.

Montezuma wanted to ask Huemac for protection and to be his servant, so that he could avert the catastrophe predicted by these

omens. Three times Montezuma sent emissaries, and three times Huemac refused. Huemac recommended instead that Montezuma abandon

all luxuries, the flowers and the perfumes, make penance and eat the same food as peasants, drink only boiled water, and then

maybe he would help him. To his anguish, Montezuma was unable to obey the commandment. These legends are a part of the post-conquest

rationalization by the Aztecs of their defeat and show Montezuma as indecisive, vain, and superstitious and ultimately the

cause of the fall of the Aztec Empire. In 1517, Montezuma received first reports of Europeans landing on the east coast of

his empire; this was the expedition of Juan Grijalva who had landed on San Juan Ulúa, which although within Totonac territory

was under the auspices of the Aztec Empire. Montezuma ordered that he be informed of any new sightings of foreigners at the

coast and posted extra watch. This meant that when the expedition of Cortés arrived in 1519 Montezuma was immediately informed

and he sent emissaries to meet the newcomers, one of them known to be an Aztec noble named Tentlil in the Nahuatl language

but referred to in the writings of Cortés and Bernal Díaz del Castillo as "Tendile". As the Spaniards approached Tenochtitlan

they made an alliance with the Tlaxcalteca who were enemies of the Aztec Triple Alliance and they helped instigate revolt

in many towns under Aztec dominion. Montezuma of course was aware of this and he sent gifts to the Spaniards, probably in

order to show his superiority to the Spaniards and Tlaxcalteca. On November 8, 1519, Montezuma met Hernán Cortés on the causeway

leading into Mexico Tenochtitlan and the two leaders exchanged gifts. Montezuma brought Cortés to his palace where the Spaniards

lived as his guests for several months. Montezuma continued governing his empire and even undertook conquests of new territory

during the Spaniard's stay at Tenochtitlan. However, at some time during that period Montezuma became a prisoner in his own

house. Exactly why this happened is not clear from the extant sources. But the Aztec nobility grew displeased with the large

Spanish army staying in Tenochtitlan, and Montezuma told Cortés that it would be best if they left. Shortly thereafter Cortés

left to fight Panfilo de Narvaez and during his absence the massacre in the main temple turned the tense situation between

the Spaniards and Aztecs into direct hostilities, and Montezuma became a hostage used by the Spaniards to assure their security.

In the subsequent battles with the Spaniards after Cortés' return, Montezuma was killed. The details of his death are unknown:

different versions of his demise are given by different sources. In his Historia, Bernal Díaz del Castillo states that on

July 1, 1520, the Spanish forced Montezuma to appear on the balcony of his palace, appealing to his countrymen to retreat.

The people were appalled by their emperor's complicity and pelted him with rocks and darts. He died a short time after that.

There are quite different meanings about his death. Bernal Díaz gives this account: Montezuma was hit by three stones, one

on the head, one on the arm, and one on the leg; and though they begged him to have his wounds dressed and eat some food and

spoke very kindly to him, he refused. Then quite unexpectedly we were told that he was dead. Cortés similarly reported that

Montezuma died wounded by a stone thrown by his countrymen. On the other hand, the indigenous accounts claim that Montezuma

was killed by the Spanish prior to their leaving the city. For example, according to Father Sahagun's Tlatelolcan informants,

Alvarado "garrotted all the nobles he had in power", and Montezuma’s body was found in the street with sword wounds

three days after the killings. In the Ramirez Codex, an anonymous account by a Christianized Aztec, the Spanish priests are

criticized for searching for gold rather than administering the Last Rites. Some modern scholars have preferred the indigenous

accounts over the Spanish ones. They surmise that the Spanish killed Montezuma once his inability to pacifying the Aztec people

had made him useless. The Spaniards were forced to flee the city and they took refuge in Tlaxcala, and signed a treaty with

them to conquer Tenochtitlan, offering to the Tlaxcalans freedom from any kind of tribute and the control of Tenochtitlan.

Montezuma was then succeeded by his brother Cuitláhuac, who died shortly after during a smallpox epidemic. He was succeeded

by his adolescent nephew, Cuauhtémoc. During the siege of the city, the sons of Montezuma were murdered by the Aztec, possibly

because they wanted to surrender. By the following year, the Aztec empire had entirely succumbed to the Spanish. After the

conquest, Montezuma’s daughter, Techichpotzin, was considered the heiress to the king's wealth following Spanish customs

and given the name "Isabel". She was married to different conquistadors who laid claim to the heritage of the Aztec emperor.

The title Montezuma still is the name of a Spanish house. From: historical accounts & records

LINK TO BRAVEHORSE WARRIORS VOLUME TWO

|