|

FORT MOUNTAIN, GEORGIA

The legends about a prehistoric white race are the most popular of all. They are based on tales handed down by word of mouth,

among the Cherokee Nation. Ancient tribal chiefs said their early forebears passed along to posterity, these stories that

people with fair skin, blond hair and blue eyes occupied the mountain areas until Cherokee Invaders finally dispersed them

with great slaughter. The Native American tales described the white tribesmen as "moon-eyed" people; because it was said they

had keen eyesight at night, but were nearly blind in daylight. Some historians give a measure of credence to a very old legend

that a man named Prince Madoc and 200 adventurous Welshmen from Wales in 11 ships in the year 1170 and landed on what is now

the Alabama coast near Mobile. The story relates that the ships returned to Wales for more settlers, leaving Madoc and his

200 followers to establish a colony. Repeated attacks by the Native Americans drove the Welshmen far into the North, until

they found refuge in what is now the north Georgia Mountain area. There they lived in peace for many years, so the story goes,

until the Cherokee killed many of them and intermarried with the survivors. Fort Mountain State Park is situated in the Chattahoochee

National Forest close to the Cohutta Wilderness area.

THE STORY OF THE WALL AT FORT MOUNTAIN

Fort Mountain derives its name from an ancient rock wall which protects the highest point of the mountain. The wall, extending

885 feet, is seven feet in height at its tallest point and shows evidence of being much higher when first built. Up to 12

feet wide, with 29 pits scattered at regular intervals along its length, the wall is without peer in southeastern archaeology.

Archaeological findings indicate that the ancient fortification long predates the Cherokees who were living there in the 1700s.

These moon-eyed people were said to have fair skin, blonde hair and blue eyes. Some theorists believe that these moon-eyed

people built the wall as a part of sun worship, while others believe it was used in athletic games. Some of the other thoughts

pushed from time to time are that Hernando de Soto, who spent two peaceful weeks here in 1540 built it or that the Cherokees

created the wall to defend themselves against Creek attackers. Currently, most scholars believe that the wall originated about

1100A.D. and has a religious purpose. Many early cultures built structures related to astronomical events. In this case the

wall runs east to west around a precipice. The effect is that the sun illuminates one side of the wall at sunrise and on the

other side at sunset. Native American cultures worshipped the sun and all things in nature. The absence of religious artifacts

supports this theory since it was common practice for Native Americans to take ceremonial objects with them when they moved.

The mysterious wall is said to have been built by Welsh Explorers as a fortification against hostile Indians and for ancient

ceremonies. Several petroglyphs support the existence of this legend. Following is a paper which could very well explain

and clarify the story.

A CONSIDERATION: WAS AMERICA DISCOVERED IN 1170 by PRINCE MADOC AB OWAIN GWYNEDD OF WALES? History, not unnaturally, tends

to be written by historians, but seldom by geographers, or seamen, or interpreters of legend, and much of the early history

of the world has suffered in consequence. In 1170 A.D., a certain Welsh prince, Madoc ab Owain Gwynedd, sailed away from his

homeland, which was filled with war and strife and battles between his brothers. Yearning to be away from the feuds and quarrels,

he took his ships and headed west, seeking a better place. He returned to Wales brimming with tales of the new land he found--warm

and golden and fair. His tales convinced more than a few of his fellow countrymen, and many left with him to return to this

wondrous new land, far across the sea. This wondrous new land is believed to be what is now Mobile Bay Alabama. Time has left

several blank pages between the legend of Madoc and the "history" of America, with its reports of white Indians who speak

Welsh, and these blank pages have been the subject of much controversy in certain circles over the five centuries since Columbus

discovered the New World. Although in 1500 it may have made a significant difference exactly who first discovered--and therefore

lay claim to--the North American Continent, that time has passed. In 1999, the relevance of the subject rests in the area

of its interest to a student of history, rather than its significance to the world. This admission made, the story of Madoc,

and the chronicle of the "Welsh Indians" will be explored, and the connection between the two will be considered for its place

in that blank chapter of history. Owain Gwynedd, succeeded his father, Gruffydd ap Cynan as ruler of the Gwynedd province

of Wales in 1138. His thirty-two-year reign was a bloody and turbulent time of constant warfare between the Norman barons

and the Welsh chieftans. Though he strived during his rule for both the prosperity of his people and the unity of all Welsh

kingdoms against the English. His aims were hindered by the treacherous feuding within his own ranks. Although well known

for his ". . .fierce and brutal penalties for disloyalty. .", he was nevertheless remembered as a mighty soldier and a great

leader by his own people, and considered the "King of Wales" by those in England and other lands. Owain was said to have had

seventeen sons, including Madoc, and at least two daughters, although few were considered legitimate by the churchmen of the

time. This confused situation led to bitter dispute as to who among his sons would succeed him and his death in 1169 plunged

his country into civil war. It was this civil war from which Madoc fled. His story was repeated by bards and recorded throughout

the next four centuries by various historians, but concise and detailed accounts would not be found until after the introduction

of printing. Perhaps the earliest printed account of Madoc's story is from Dr. David Powel's The Historie of Cambria published

in 1584:~ Madoc. . .left the land in contention betwixt his brethern and prepared certain shipps with men and munitions

and sought adventures by seas, sailing west. . .he came to a land unknown where he saw manie strange things. . . . Of the

viage and returne of this Madoc there be manie fables faimed, as the common people do use in distance of place and length

of time, rather to augment than diminish; but sure it is that there he was. . . .And after he had returned home, and declared

the pleasant and fruitfulle countries that he had seen without inhabitants, and upon the contrarie part, for what barren and

wilde ground his brethern and nepheues did murther one another, he prepared a number of shipps, and got with him such men

and women as were desirous to live in quietnesse, and taking leave of his freends tooke his journie thitherward againe. .

. This Madoc arriving in the countrie, into which he came in the yeare 1170, left most of his people there, and returning

back for more of his own nation, acquaintance, and friends, to inhabit that fayre and large countrie, went thither againe.

~ Madoc's story was related in A Brief Description of the Whole World (1620); a version was told by Sir Thomas Herbert in

the last section of his Relation of Some Years Traveled (1626), based on what Sir Thomas said were records of "200 years agoe

and more" The Dutch writer Hornius tells of Madoc in De Originibus Americanis (1652); and Richard Hakluyt's Principal Navigations

(1600) establishes the fact that the story of Madoc existed before the time of Columbus. Hakluyt, a geographer as well as

an historian, had a reputation for being a perfectionist. His work is thoroughly researched and supported by foreign as well

as British sources. Gutyn Owen was a renowned Welsh historian and genealogist with a well documented career and a number of

famous works of Welsh literature to his credit. His writings are cited as sources of Madoc's story by a number of authors,

and the fact that his account of Madoc was written before 1492 ". . .refutes the criticism that the Madoc story was brought

forward after 1492 in order that Great Britain could claim prior rights to the new world." Among the writings of Madoc's story

are found suppositions of his landing in the West Indies, in Mexico, and in the Alabama-Florida region of North America. The

scope of this paper dictates pursuit of the latter theory--more specifically, Mobile Bay, Alabama. The choice of Mobile Bay

as Madoc's landfall and the starting point for his colonists is grounded in two main areas. One is the logical assumption

that the ocean currents would have carried him into the Gulf of Mexico. Once there and seeking a landing site, he would have

been attracted to the perfect harbor offered in Mobile Bay, as were later explorers Ponce de Leon, Alonzo de Pineda, Hernando

de Soto, and Amerig Vespucci. The second, and more convincing reason, is a series of pre-Columbian forts built up the Alabama

River, and the tradition handed down by the Cherokee Indians of the "White People" who built them. Testimony includes a letter

dated 1810 from Governor John Seiver of Tennessee in response to an inquiry by Major Amos Stoddard. The letter, a copy of

which is on file at the Georgia Historical Commission, recounts a 1782 conversation Sevier had with then 90-year-old Oconosoto,

a Cherokee, who had been the ruling chief of the Cherokee Nation for nearly sixty years. Seiver had asked the Chief about

the people who had left the "fortifications" in his country. The chief told him: "they were a people called Welsh and they

had crossed the Great Water." He called their leader "Modok." If true, this fits with the known history of 12th century Welsh

Prince Madoc. He further related: "It is handed down by the Forefathers that the works had been made by the White people

who had formerly inhabited the country. . ." and gave him a brief history of the "Whites." When asked if he had ever heard

what nation these Whites had belonged to, Oconostota told Seiver that he ". . .had heard his grandfather and father say they

were a people called Welsh, and that they had crossed the Great Water and landed first near the mouth of the Alabama River

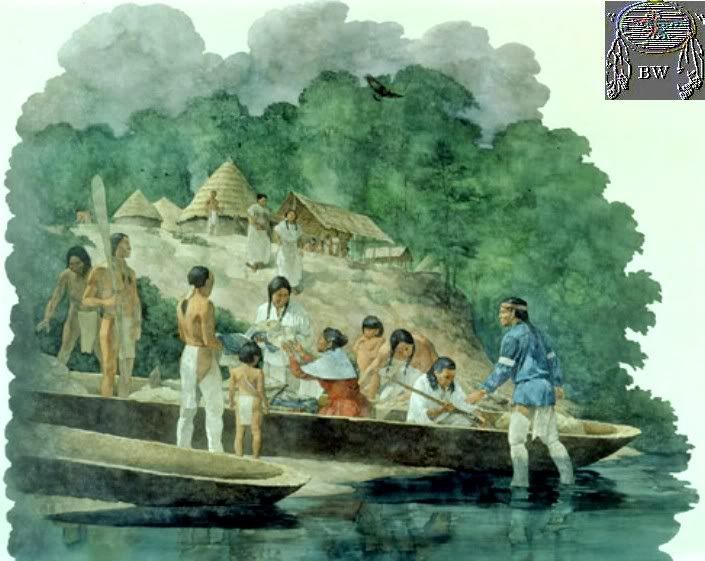

near Mobile. . .." Three major forts, completely unlike any known Native American structure, were constructed along the route

settlers arriving at Mobile Bay would have taken up the Alabama and Coosa rivers to the Chattanooga area. Archaeologists have

testified that the forts are of pre-Columbian origin, and most agree they date several hundred years before 1492. All are

believed to have been built by the same group of people within the period of a single generation, and all bear striking similarities

to the ancient fortifications of Wales. The first fort, erected on top of Lookout Mountain, near DeSoto Falls, Alabama, was

found to be nearly identical in setting, layout, and method of construction, to Dolwyddelan Castle in Gwynedd, the birthplace

of Madoc. The situation of the forts, blended with the accounts given by the Indians of the area, has led to a plausible reconstruction

of the trail of Madoc's colonists. The settlers would have traveled up the Alabama River and secured themselves at the Lookout

Mountain site, which took months, maybe even years to complete. It is presumed the hostility of the Indians forced them to

move on up the Coosa River, where the next stronghold was established at Fort Mountain, Georgia. Situated atop a 3,000 foot

mountain, this structure had a main defensive wall 855 feet long, and appears to be more hastily constructed than the previous

fort. Having retreated from Fort Mountain, the settlers then built a series of minor fortifications in the Chattanooga area,

before moving north to the forks of the Duck River (near what is now Manchester, Tennessee), and their final fortress, Old

Stone Fort. Formed by high bluffs and twenty-foot walls of stone, Old Stone Fort's fifty acres was also protected by a moat

twelve hundred feet long. Like the other two major defense works, Old Stone Fort exhibits engineering proficiency well beyond

the skills of the Indians. The trail of the settlers becomes more speculative with the desertion of Old Stone Fort. Chief

Oconostota, in relating his tribal history, tells of the war that had existed for years between the White people who had built

the forts and the Cherokee. Eventually a treaty was reached in which the Whites agreed to leave the area and never return.

According to Oconostota, the Whites followed the Tennessee River down to the Ohio, up the Ohio to the Missouri, then up the

Missouri ". . .for a great distance. . .but they are no more White people; they are now all become Indians...." Chief Oconostota's

testimony has been very thoroughly followed up by later historians, and several points have been corroborated with other reports

of "bearded Native Americans" and their trek upriver in retreat from hostile natives. Throughout the years ". . .there was

abundant evidence. . .that travelers and administrators had met Indians who not only claimed ancestry with the Welsh, but

spoke a language remarkably like it." It must be assumed that the remaining settlers were eventually assimilated by Native

American, and that by the early eighteenth century very few traces of their Welsh ancestry remained.

Although several tribes have been considered as possible descendants of the Welsh settlers, the most likely is the Mandan

tribe, who once inhabited villages along tributaries of the Missouri River. These Mandan villages were visited in 1738 by

a French explorer, The Sieur de la Verendrye, and he kept a detailed journal describing the people and their villages. At

the time of Verendrye's visit, the tribe numbered about 15,000 and occupied eight permanent villages. The Mandan chief told

him that the tribe's ancestors had formerly lived much farther south but had been driven north and west by their enemies.

Verendrye described the Mandans as "white men with forts, towns and permanent villages laid out in streets and squares." He

indicated that their customs and lifestyle were totally different from other tribes he had encountered, and was the first

of many to remark about the beards of their men, the grey hair of their older people, and the magnificent beauty of their

women! The Mandans had several visitors throughout the next century, (including Louis and Clark in 1804), each one reiterating

the striking differences in their culture and appearance. The Mandans had been repeatedly driven out of their villages and

forced upriver by their continual conflicts with the Sioux. By the 1830s, when George Catlin made his memorable visit, their

numbers had decreased by two thirds. Catlin spent several years living with, studying, and painting various Indian tribes,

and in 1841 published his classic work: Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs and Condition of the Native American. He

devoted sixteen of his fifty-eight chapters to the Mandans, explaining: I have dwelt longer on the history and customs of

these people than I have or shall on any other tribe. . .because I have found them a very peculiar people. From the striking

peculiarities in their personal appearance, in their customs, traditions, and language, I have been led conclusively to believe

that they are a people of a decidedly different origin from that of any other tribe in these regions. Catlin was so impressed

by these differences that he speculated that the Mandan tribe could very well be the remains of the lost colony of Madoc.

Although he had no Welsh ancestry himself, and no particular motivation for pursuing this theory, he went to great effort

to investigate their origin and traced their migration up the Missouri and Ohio Rivers. His book contains several pages, including

a vocabulary comparing numerous Mandan and Welsh words, in support of his theory. He reflects, "If my reasons do not support

me, they will at least be worth knowing, and may be the means of eliciting further and more successful enquiry." When Catlin

left the Mandans in August, 1833, he did not know his would be the last, and probably most important, account of the Mandan

tribe. They had survived a trans-Atlantic voyage; they had survived the Cherokee; they had survived an eighteen-hundred mile

migration; they had even managed to survive the Sioux. Like so many other Indian tribes, they did not survive the smallpox

epidemic introduced to them by traders in 1837. Now considered extinct, the Mandans do however, lay claim to the distinction

of being the only Indian tribe never to have been at war with the United States. Throughout the centuries, scholars and historians

have argued for and against the Madoc story. The classic work denying the entire idea was written in 1858 by the distinguished

Welsh scholar, Thomas Stephens. So thorough and detailed was his essay, it was considered the best work submitted for a competition

held on the subject. Ironically, his prize was denied as his article refuted the theme rather than proved it. Current naysayers

include Samuel Eliot Morison, who emphatically dismisses the entire subject as nothing more than a fable. He accepts no connections

between the White Settlers and the Chattanooga area forts. He renounces all associations linking the tales of the Welsh Indians

to the Mandans, acknowledging only the report of John Evans indicating that he met no Welsh speaking Indians when he spent

one winter with the Mandans in the 1790s. Although Evans' character itself and motives for the report are questionable, Morison

embraces his brief findings, while only mentioning George Catlin in his bibliography, stating that his Notes and Letters "....gave

the legend a new lease on life. . .with phony comparative vocabulary." Where Richard Deacon devotes an entire book to detailed

research on the subject, Morison only mentions it in his notes, indicating that Deacon ". . .pulls all the travelers tales

together. . .he feels there must be something in it, but cannot say what." He attributes the claim of discovery to the eagerness

of the Tudor court historians (of Welsh descent) ". . .to claim priority over Spain in the New World." His basic attitude

may be summarized with the following line: "As Bernard De Voto well observed, the insubstantial world of fairies and folklore

is as real as the visible world to Celtic peoples." Not everyone shares Morison's view, for in November, 1953 a memorial tablet

was erected at Fort Morgan, Mobile Bay, Alabama by the Virginia Cavalier Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution,

which reads: In memory of Prince Madoc, a Welsh explorer, who landed on the shores of Mobile Bay in 1170 and left behind,

with the Native Americans, the Welsh language.

From Fort Mountain research & (directions to Fort Mountain):

http://gastateparks.org/net/go/parks.aspx?LocationID=42&s=0.0.1.5

LINK TO BRAVEHORSE WARRIORS VOLUME TWO

|