|

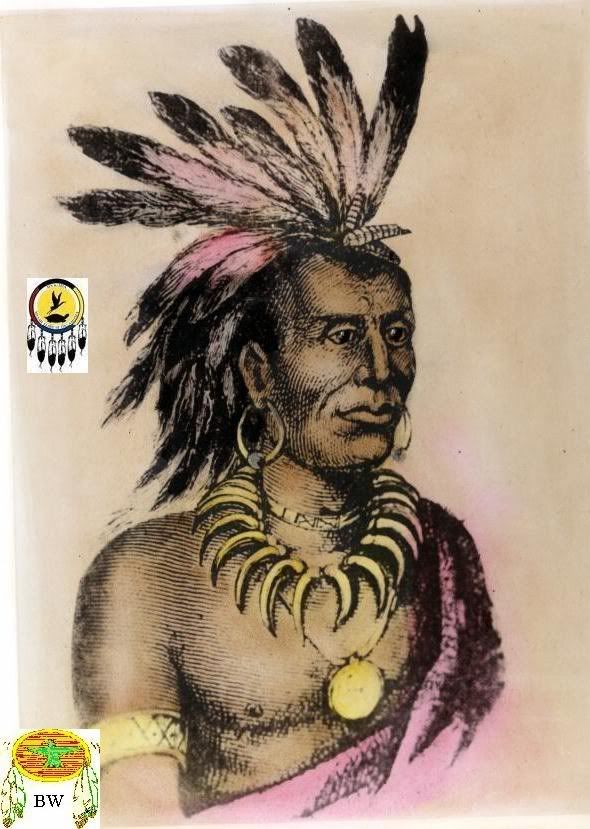

Chief Little Turtle

(1752-1812)

Warriors Citation

Little Turtle, Warrior leader of the Miami Indians of the late 18th century, was born on the Eel River some 20 miles northeast

of Fort Wayne, Indiana. A lover of good companionship, fine food and good humor, Little Turtle was a powerful orator who counseled

moderation at all times. Six feet in height, he was noteworthy for his subtlety and circumspectness. Little Turtle became

one of the most successful woodland military commanders of his time, but after the Treaty of Greenville (1795) he tried to

keep his tribe at peace and at the same time protect its land from an imperialist United States.

During the American Revolution, the Miami gave some assistance to the British, and Little Turtle may have participated in

the defeat of a detachment led by Augustin de La Balme on its way to attack the British post of Detroit in 1780. After the

Peace of Paris (1783) the Native Americans continued to resist American expansion north of the Ohio, and Little Turtle probably

led small forays against the white settlements. By 1790 he had become the chief warrior leader of the Miami, serving under

a civil chief, Le Gris.

Before 1790 the Miami villages at the head of the Maumee (near present-day Fort Wayne) had become the focus for many Native

Americans displaced by fighting with the Kentuckians farther east, particularly Shawnees and Delawares. When Brigadier General

Josiah Harmar led almost 1,500 troops to attack this concentration in October 1790, burning the Native Americans villages,

Little Turtle was one of the chiefs orchestrating the defense. The following year an American army general, Arthur St. Clair,

advanced upon the Miami towns, but his troops were overwhelmingly defeated in November 1791 by a multi-tribal force. Miami

accounts credit Little Turtle with being the overall Native American commander on this occasion, although a number of other

sources name Blue Jacket.

While Little Turtle's influence was at its apogee, the triumph was overshadowed by General James Wilkinson's unexpected 1791

expedition, which not only destroyed Little Turtle's village on the Eel River but also captured his daughter. When he signed

the treaty of Greenville, ending the war, he reputedly said that he was one of the last to sign and that he would be the last

to break the treaty.

Little Turtle strongly urged abstinence from alcohol on his fellow Miami and made efforts to have them learn the principles

of farming. On one of several trips to the East Coast, he visited Quakers in Pennsylvania in a successful attempt to get farming

instructors. This accommodating attitude led him to sign three other major land-losing treaties with the United States. The

resultant land cessions made many Miami suspect his integrity; his nephew Richardville died a very rich man. Moreover, some

of his critics were right in stating that the Americans wanted nearly all of the Native American land. Little Turtle's tribal

strategy was also doomed by the reluctance of the Miami to alter their older lifestyle. On the other hand, the marked displeasure

of Little Turtle and William Wells, Little Turtle's son-in-law (a white captive), at American land hunger also caused American

officials, such as William Henry Harrison, governor of Native American Territory, and the Indian agent John Jonston, to distrust

him. Nevertheless, Little Turtle's counsels kept the majority of Miami from actively joining Tecumseh's anti-American confederation.

In addition, Kentucky relatives of Wells fought prominently in the Battle of Tippecanoe (1811), which severely checked Tecumseh's

progress. Little Turtle's reputation began to recover after this military defeat of the hostile confederation, and it was

with good reason that the American government buried Little Turtle with full military honors. MICHIKINAKOUA (Michikiniqua,

Me-She-Kin-No-Quah, Meshecunnaqua, Little Turtle), Miami war chief; b. mid 18th century, son of Aque-Noch-Quah, a Miami war

chief; rumoured to have Mahican or even French blood; m. secondly Polly Ford, a white captive; d. 14 July 1812 at Fort Wayne

(Ind.).

Chief Little Turtle first came to white attention at the time of the American revolution. Like other Miami chiefs an ally

of the British, in 1780 he led his warriors in the destruction at the Miamis Towns (Fort Wayne) of a force under Augustin

Mottin de La Balme, who was attempting to re-establish French control in the Ohio valley. The tribes south of the Great Lakes

received their supplies from the British, who after 1780 encouraged the formation of a confederacy to oppose American expansion

[see Thayendanegea]. When in spite of official promises American settlers moved north of the Ohio, war parties from the confederacy

attacked them. Little Turtle led many such raids and by 1790 had become the leader of the united war parties of the confederacy.

After 1789 the stronger central government created by a new constitution in the United States made possible plans to retaliate

against the confederated tribes. Little Turtle led the Indians in two of the three major battles that ensued. In October of

1790 he decimated the forces under Josiah Harmar which had come to attack the Miami, Shawnee, and Delaware villages at the

Miamis Towns. Although Harmar burned 300 houses and 20,000 bushels of corn just at the onset of winter, and although smaller

American attacks followed, the Indians were not demoralized. In November 1791 near the Miamis Towns Little Turtle inflicted

on Arthur St Clair’s expedition losses of 630 killed and 264 wounded, the most casualties ever suffered by Americans

in a single offensive against Indians. He is reported to have gone to the Montreal area following this victory in an effort

to recruit more Indians for the spring’s campaigning.

British and Indian hopes were now high that the Americans would agree to limit their expansion and allow the formation of

an Indian state south of Lake Erie, but the Americans, more determined than ever, were preparing another expedition. Bolstered

by inflammatory talk from Lord Dorchester [Guy Carleton] and John Graves Simcoe, which seemed to promise military aid if needed,

the confederacy braced itself to meet the army under Anthony Wayne which began advancing in the autumn of 1793. Many residents

of the Miamis Towns and vicinity had moved to the Glaize (Defiance, Ohio), farther from the American frontier; Little Turtle

himself had left his customary village on the Eel River (Ind.) to live there. After unsatisfactorily harassing Wayne’s

lines of supply and communication for months and sounding out the British at Detroit (Mich.) about the possibility of aid,

Little Turtle advised the confederacy that more would be gained by negotiating than by fighting. His advice was rejected,

and he turned over command to the Shawnee chief Blue Jacket [Weyapiersenwah], retaining only the leadership of his Miami warriors.

A few days later, on 20 Aug. 1794, Blue Jacket was outgeneralled in the battle of Fallen Timbers (near Waterville, Ohio).

Losses on both sides were about equal, but the Indians abandoned the field. The who refused them aid and shelter at nearby

Fort Miamis (Maumee).

Wayne remarked on the agricultural nature of the Glaize settlements, writing: “The very extensive and highly cultivated

fields and gardens show the work of many hands. The margin of those beautiful rivers [the Maumee and the Auglaize] appear

like one continued village for a number of miles both above and below this place; nor have I ever beheld such immense fields

of corn in any part of America from Canada to Florida.” This area was not placed within the boundaries exacted by the

Americans at the Treaty of Greenville the following summer, but the Indians, their confederacy in shambles, surrendered most

of present-day Ohio, a portion of Indiana, and other tracts. Little Turtle made an eloquent though unsuccessful attempt to

secure better terms and signed the agreement reluctantlet he never broke the promises of peace it contained. In return the

Americans built him a house in his old village on the Eel River, provided for the purchase of a black slave for him, and financed

extensive travel to the east. At Philadelphia, Pa, in 1797 Gilbert Stuart painted his portrait. There also in 1798 he impressed

the Comte de Volney, a French philosophe, with his wit and wisdom. During one of a series of interviews, Volney asked him

what surprised him most about Philadelphia. “The extraordinary diversity of personal appearance among the whites and

their great numbers,” he replied. “They spread like oil on a blanket; as for us, we melt like snow in the spring

sunshine; if we do not alter course, the race of red men cannot possibly survive.” At Washington, D.C., in 1802 Little

Turtle stirred officials with his pleas for prohibition of alcohol as well as training in farming and metal-craft for his

people.

After the disintegration of the confederacy in 1795 Little Turtle, like many of his contemporaries, surrendered hope

for a pan-Indian movement and concentrated on the interests of his tribe alone. His opposition after 1806 to the new confederacy

being created by the Prophet [Tenskwatawa*] and Tecumseh was based on several considerations. By its insistence that Indian

land was owned by all tribes in common, the confederacy threatened Miami land claims, and by advocating the removal of those

chiefs who had already sold land to the Americans, it endangered his leadership. Moreover he was convinced that the Americans

could not be successfully opposed by any combination of tribes. He was more effective than most chiefs in preventing his warriors

from joining the confederacy; yet the Americans never completely trusted him. His prestige among the tribes in general was

revived somewhat when Governor William Henry Harrison of Ohio devastated the headquarters of the confederacy at Tippecanoe

(near Lafayette, Ind.) in 1811.

Little Turtle died at Fort Wayne on 14 July 1812 following treatment by an army doctor for gout. As was customary with

Miamis, he was buried wearing his silver jewellery, which included several pieces with the mark of Robert Cruickshank of Montreal.

Lesser chiefs could not restrain the young Miami warriors from joining the new confederacy in increasing numbers after his

death. In September the Americans burned his village on the Eel River but they spared his property as a mark of respect. He

was, in his prime, a strong defender of native rights and was remembered as a hero among the Miamis. From: historical accounts

& records

LINK TO BRAVEHORSE WARRIORS VOLUME TWO

|