|

BRAVEHORSE WARRIOR Ponekeosh

Mississauga Ojibwa Warrior

Chief Ponekeosh

Warrior Citation

PONEKEOSH (Bonekeosh), Mississauga Ojibwa chief; b. c. 1810–20, likely at or near the Mississagi River, Upper Canada;

d. 1891. Nothing is known of Ponekeosh’s family or early life. He was one of the chiefs or “Principal Men”

of the clusters of Indian families that hunted, fished, and trapped on the north shores of lakes Huron and Superior and inland.

Many Ojibwa headmen knew English and French. They acted as mediators, interpreters, trading captains, and entrepreneurs, and

they were often seen by government as “natural” leaders. Ponekeosh, however, seems to have been a man of ability

who may not have understood European languages or the world of the white man. Yet by 1850 he had become prominent enough to

be recognized as a leader in the negotiations leading up to the treaty between William Benjamin Robinson, representing the

province of Canada, and the Native Americans who lived on the north shore of Lake Huron. During the late 1840s a boom in copper

mining had developed around lakes Huron and Superior as non- Native Americans began to take a greater interest in exploiting

the economic assets of the area. The result was growing tension between miners and Native Americans over surveying and use

of the lands, which culminated in violence at the Mica Bay site of the Montreal Mining Company in November 1848. The next

year a government commission of inquiry into the Indian claims was established, and its report became the basis for the treaty

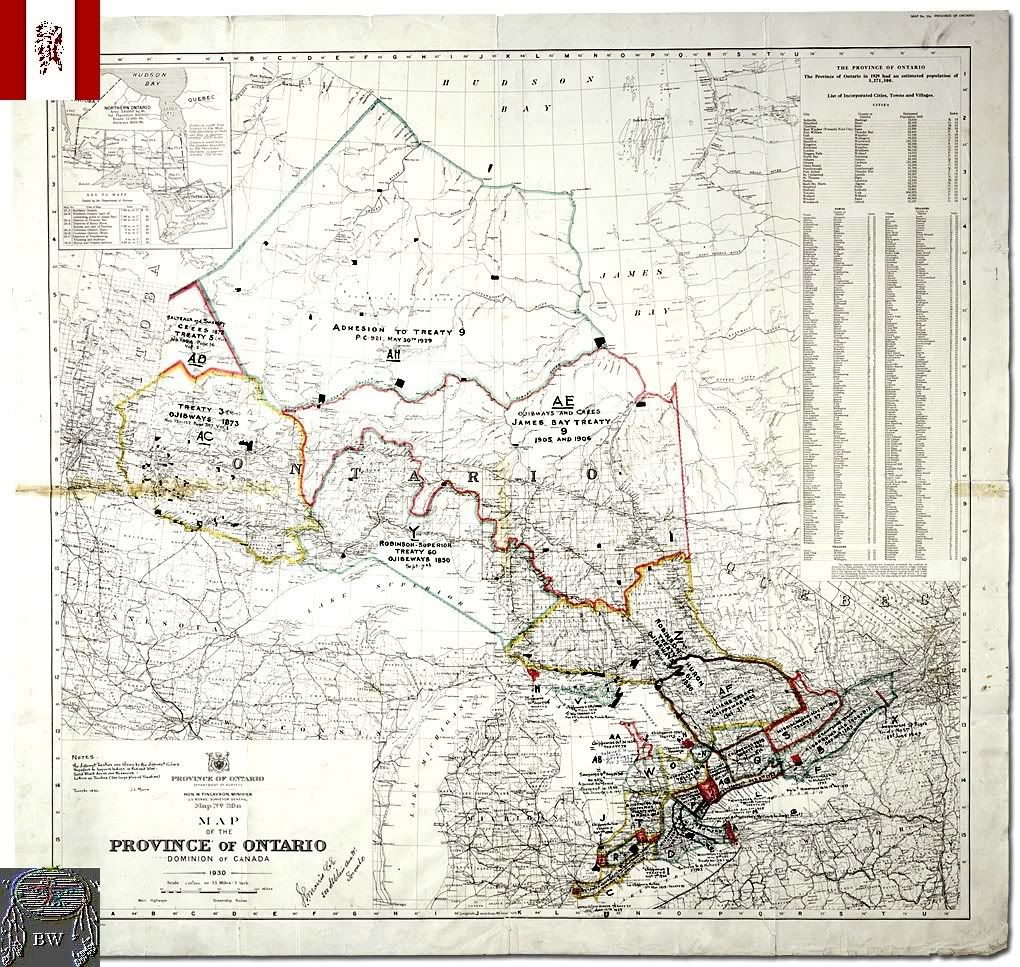

of 1850. Ponekeosh took part in the treaty negotiations of early September 1850 at Sault Ste Marie and signed the treaty on

behalf of the Mississagi River band, but he was not one of the prominent Indian speakers. The “Schedule of Reservations”

in the treaty stated that the Mississagi band’s reserve would include the land fronting on Lake Huron between the Miss

issagi and Blind rivers and up the rivers to the “first rapids.” Although the Native American bands soon received

most of the payments in kind promised by the treaty, it took longer to survey the reserves. On 11–12 Sept. 1852 surveyor

John Stoughton Dennis, his crew, and John William Keating of the Native American Department arrived at the Mississagi River

to survey the northern boundary of Ponekeosh’s reserve. Ponekeosh was away, and Dennis and Keating waited until he returned

before making a decision. In the mean time they reconnoitred the area and made a critical mistake. Dennis recognized that

the first large rapids on the Mississagi were 16 to 18 miles from Lake Huron, but he located the Blind River incorrectly and

concluded that the reserve would therefore involve an area much larger than the treaty intended. When Ponekeosh arrived he,

as it appears, correctly described the treaty area but Dennis concluded that Ponekeosh was uncertain about “the points

between which he had intended to include his Reserve” and talked the chief into accepting a smaller area. He reported

that Ponekeosh had stated he would be “satisfied.” Had Ponekeosh understood he was agreeing to a much smaller

area it is unlikely he would have been content. The northern boundary of the smaller area was then surveyed. Ponekeosh is

reputed to have surrendered the entire reserve to the crown in 1865. Much of the land was surveyed, subdivided, and sold in

the late 19th century.

Chief Ponekeosh

Warrior Citation

PONEKEOSH (Bonekeosh), Mississauga Ojibwa chief; b. c. 1810–20, likely at or near the Mississagi River, Upper Canada;

d. 1891. Nothing is known of Ponekeosh’s family or early life. He was one of the chiefs or “Principal Men”

of the clusters of Indian families that hunted, fished, and trapped on the north shores of lakes Huron and Superior and inland.

Many Ojibwa headmen knew English and French. They acted as mediators, interpreters, trading captains, and entrepreneurs, and

they were often seen by government as “natural” leaders. Ponekeosh, however, seems to have been a man of ability

who may not have understood European languages or the world of the white man. Yet by 1850 he had become prominent enough to

be recognized as a leader in the negotiations leading up to the treaty between William Benjamin Robinson, representing the

province of Canada, and the Native Americans who lived on the north shore of Lake Huron. During the late 1840s a boom in copper

mining had developed around lakes Huron and Superior as non- Native Americans began to take a greater interest in exploiting

the economic assets of the area. The result was growing tension between miners and Native Americans over surveying and use

of the lands, which culminated in violence at the Mica Bay site of the Montreal Mining Company in November 1848. The next

year a government commission of inquiry into the Indian claims was established, and its report became the basis for the treaty

of 1850. Ponekeosh took part in the treaty negotiations of early September 1850 at Sault Ste Marie and signed the treaty on

behalf of the Mississagi River band, but he was not one of the prominent Indian speakers. The “Schedule of Reservations”

in the treaty stated that the Mississagi band’s reserve would include the land fronting on Lake Huron between the Miss

issagi and Blind rivers and up the rivers to the “first rapids.” Although the Native American bands soon received

most of the payments in kind promised by the treaty, it took longer to survey the reserves. On 11–12 Sept. 1852 surveyor

John Stoughton Dennis, his crew, and John William Keating of the Native American Department arrived at the Mississagi River

to survey the northern boundary of Ponekeosh’s reserve. Ponekeosh was away, and Dennis and Keating waited until he returned

before making a decision. In the mean time they reconnoitred the area and made a critical mistake. Dennis recognized that

the first large rapids on the Mississagi were 16 to 18 miles from Lake Huron, but he located the Blind River incorrectly and

concluded that the reserve would therefore involve an area much larger than the treaty intended. When Ponekeosh arrived he,

as it appears, correctly described the treaty area but Dennis concluded that Ponekeosh was uncertain about “the points

between which he had intended to include his Reserve” and talked the chief into accepting a smaller area. He reported

that Ponekeosh had stated he would be “satisfied.” Had Ponekeosh understood he was agreeing to a much smaller

area it is unlikely he would have been content. The northern boundary of the smaller area was then surveyed. Ponekeosh is

reputed to have surrendered the entire reserve to the crown in 1865. Much of the land was surveyed, subdivided, and sold in

the late 19th century.

Soon after Ponekeosh died in 1891 his successor submitted to government officials on behalf of the Mississaugas an

accurate Indian map which depicted the area requested by Ponekeosh in 1850 and 1852, and asked that the boundaries of the

reserve be investigated. Although an inquiry took place, bureaucrats contended on the basis of Dennis’s documents and

little else that the band was wrong. Nothing further was done. The issue was raised again by the band in the 1970s. A thorough,

independent investigation was carried out in the 1980s, and negotiations are currently (1989) under way with a view to fulfilling

the crown’s promise of the reserve as initially requested by Ponekeosh. Ponekeosh was not, in the estimation of white

society, a prominent Native American leader like Tecumseh or Big Bear [Mistahimaskwa], yet his involvement, like that of other

Native American leaders, with the fulfilment of promises of the crown and with the pressure of whites for trade and colonization

is illustrative. The later struggle of the band to maintain their land and their traditional community despite the difficulties

shows the tenacity with which native customs have been maintained. From: historical accounts & records

Soon after Ponekeosh died in 1891 his successor submitted to government officials on behalf of the Mississaugas an

accurate Indian map which depicted the area requested by Ponekeosh in 1850 and 1852, and asked that the boundaries of the

reserve be investigated. Although an inquiry took place, bureaucrats contended on the basis of Dennis’s documents and

little else that the band was wrong. Nothing further was done. The issue was raised again by the band in the 1970s. A thorough,

independent investigation was carried out in the 1980s, and negotiations are currently (1989) under way with a view to fulfilling

the crown’s promise of the reserve as initially requested by Ponekeosh. Ponekeosh was not, in the estimation of white

society, a prominent Native American leader like Tecumseh or Big Bear [Mistahimaskwa], yet his involvement, like that of other

Native American leaders, with the fulfilment of promises of the crown and with the pressure of whites for trade and colonization

is illustrative. The later struggle of the band to maintain their land and their traditional community despite the difficulties

shows the tenacity with which native customs have been maintained. From: historical accounts & records

|