|

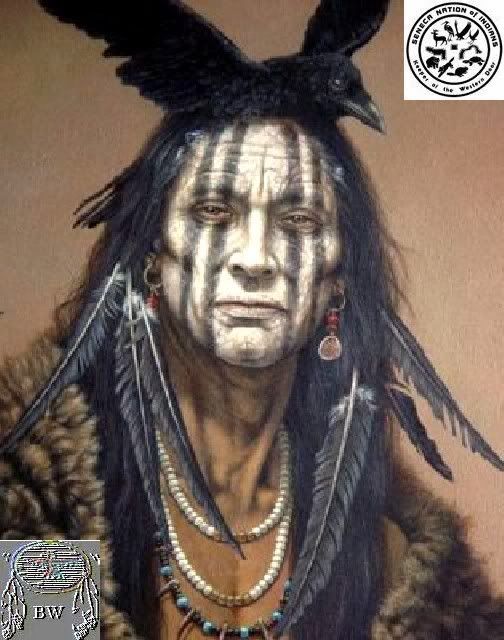

BRAVEHORSE WARRIOR Kaienakwaahton

Seneca Warrior

Chief Kaienakwaahton

Warrior Citation

KAIEĐ├KWAAHTOĐ, chief-warrior of the lower or eastern Senecas, member of the turtle clan (the name means disappearing smoke

or mist; it appears most often as spoken in Mohawk, Sayenqueraghta or Siongorochti; attempts to write the Seneca pronunciation

have included Gayahgwaahdoh, Giengwahtoh, Guiyahgwaahdoh, and Kayenquaraghton; he was also known as Old Smoke, Old King, the

Seneca King, and the King of Kanadesaga); b. early 18th century; d. 1786 on Smoke Creek (in present-day Lackawanna, N.Y.).

Kaie˝├kwaahto˝ was the son of a prominent Seneca chief in what is now western New York and resided for most of his life in

the Seneca town of Ganundasaga (Geneva). Early in life he established a military reputation in expeditions against the Cherokees

and by 1751 had apparently achieved the rank of war chief. Soon after, he began to take an active role in diplomacy with the

whites, being present at negotiations in Philadelphia in July 1754 and at Easton (Pa) four years later. It seems probable

that Kaie˝├kwaahto˝, like most of the eastern Senecas, did not espouse the French cause in the Seven Years’ War. In

the summer of 1756 his brother proclaimed his own and Kaie˝├kwaahto˝’s loyalty to the British. In January 1757 the superintendent

of northern Native Americans, Sir William Johnson, sent Kaie˝├kwaahto˝ presents to curry his favour. The Seneca chief and

a number of warriors served at Johnson’s side in the capture of Fort Niagara (near Youngstown, N.Y.) in 1759. The fall

of New France left the native population wholly dependent upon the British for manufactured goods. The Native Americans had

grown accustomed to the generosity of white diplomats anxious for their allegiance, and they still expected such liberality.

The British became parsimonious, however, and the result was the uprising of 1763. The role of Kaie˝├kwaahto˝ in this confrontation

is in doubt. The testimony of a Seneca, Governor Blacksnake [Thaonawyuthe], who knew him well and who was a boy at the time,

identifies him as the chief of the Seneca forces who inflicted a severe defeat on the British at the Niagara portage. Blacksnake’s

memory, though generally reliable, may have failed him here, for while the Senecas were fighting the British at the carrying

place, Johnson was reporting that Kaie˝├kwaahto˝ “who had ever been our freind” had been sent by the Onondagas

and other Iroquois to bring the warring Senecas to peace. Other testimony also asserts that Kaie˝├kwaahto˝ was a friend of

the crown during this war.

Chief Kaienakwaahton

Warrior Citation

KAIEĐ├KWAAHTOĐ, chief-warrior of the lower or eastern Senecas, member of the turtle clan (the name means disappearing smoke

or mist; it appears most often as spoken in Mohawk, Sayenqueraghta or Siongorochti; attempts to write the Seneca pronunciation

have included Gayahgwaahdoh, Giengwahtoh, Guiyahgwaahdoh, and Kayenquaraghton; he was also known as Old Smoke, Old King, the

Seneca King, and the King of Kanadesaga); b. early 18th century; d. 1786 on Smoke Creek (in present-day Lackawanna, N.Y.).

Kaie˝├kwaahto˝ was the son of a prominent Seneca chief in what is now western New York and resided for most of his life in

the Seneca town of Ganundasaga (Geneva). Early in life he established a military reputation in expeditions against the Cherokees

and by 1751 had apparently achieved the rank of war chief. Soon after, he began to take an active role in diplomacy with the

whites, being present at negotiations in Philadelphia in July 1754 and at Easton (Pa) four years later. It seems probable

that Kaie˝├kwaahto˝, like most of the eastern Senecas, did not espouse the French cause in the Seven Years’ War. In

the summer of 1756 his brother proclaimed his own and Kaie˝├kwaahto˝’s loyalty to the British. In January 1757 the superintendent

of northern Native Americans, Sir William Johnson, sent Kaie˝├kwaahto˝ presents to curry his favour. The Seneca chief and

a number of warriors served at Johnson’s side in the capture of Fort Niagara (near Youngstown, N.Y.) in 1759. The fall

of New France left the native population wholly dependent upon the British for manufactured goods. The Native Americans had

grown accustomed to the generosity of white diplomats anxious for their allegiance, and they still expected such liberality.

The British became parsimonious, however, and the result was the uprising of 1763. The role of Kaie˝├kwaahto˝ in this confrontation

is in doubt. The testimony of a Seneca, Governor Blacksnake [Thaonawyuthe], who knew him well and who was a boy at the time,

identifies him as the chief of the Seneca forces who inflicted a severe defeat on the British at the Niagara portage. Blacksnake’s

memory, though generally reliable, may have failed him here, for while the Senecas were fighting the British at the carrying

place, Johnson was reporting that Kaie˝├kwaahto˝ “who had ever been our freind” had been sent by the Onondagas

and other Iroquois to bring the warring Senecas to peace. Other testimony also asserts that Kaie˝├kwaahto˝ was a friend of

the crown during this war.

In Native American diplomacy it was normal to return a captive or two as part of peace overtures. At the close of the uprising

Kaie˝├kwaahto˝ approached the Seneca family that had adopted Mary Jemison and stated that he was going to return her to the

authorities at Niagara. Her foster family hid her, however, and he went to Niagara empty handed. He later found another prisoner

to deliver to the British, and on 21 March 1764 he arrived with the captive at Johnson Hall (Johnstown, N.Y.). Four days after,

he addressed a conference there, using the usual metaphors to declare the coming of peace. The hatchet was buried and washed

by a stream to the ocean where it would be lost forever, and the dead on both sides were buried so that both British and Native

Americans could forget the conflict. Kaie˝├kwaahto˝’s name heads the list of Seneca chiefs on the preliminary articles

of peace signed on 3 April. He also played a role in the conference at Fort Stanwix (Rome, N.Y.) which in 1768 attempted to

draw a firm boundary between white settlement and Native American lands. Between the treaty of Fort Stanwix and the outbreak

of the American revolution, Kaie˝├kwaahto˝ remained in the background. He was seemingly of considerable influence among the

eastern Senecas, but the focus of diplomatic activity in Indian affairs was farther west. He appeared at Johnson Hall at least

twice in 1771 with news from the west, and when Guy Johnson succeeded to the post of superintendent of northern Native Americans

he apparently cultivated the friendship of Kaie˝├kwaahto˝ in particular. The outbreak of rebellion in the British colonies

gave the ageing chief another chance to exhibit his military prowess. When the Senecas and most of the other Six Nations decided

in the summer of 1777 to enter the war as allies of the British, he and Kaiũtwah├kũ (Cornplanter) were named to

lead the Senecas in the war. Since they had as many warriors as the rest of the Six Nations combined, Kaie˝├kwaahto˝ was to

play an important part in the conflict. Although his advanced years compelled him to ride a horse on military expeditions,

he was active throughout Native Americans under his command, and the British and loyalists with whom they cooperated, ran

up an impressive series of victories on the northern frontier. Full of energy, Kaie˝├kwaahto˝ immediately left the 1777 council

to harass Fort Stanwix, now a rebel-held post, which guarded the western entrance to the Mohawk valley. It was more than a

month before Barrimore Matthew St Leger’s force arrived and the siege began in earnest. The Indians had been invited

to smoke their pipes and watch their white allies take the fort, but on 5 August word arrived from Mary Brant [Ko˝watsi├tsiaiÚ˝ni]

that Brigadier-General Nicholas Herkimer and 800 Mohawk valley militia were advancing to raise the siege. The task of intercepting

them was delegated to the Indians and a small body of loyalist troops. Kaie˝├kwaahto˝, Cornplanter, and Joseph Brant [Thayendanegea*]

were all present to lead the Six Nations warriors. The engagement at nearby Oriskany proved one of the bloodiest of the war,

given the numbers involved. The rebels lost between 200 and 500 killed, and Native American losses were significant. Although

Herkimer’s force was practically exterminated, the lack of siege artillery doomed the British attempt to take the fort.

Kaie˝├kwaahto˝ was again on the war trail in the summer of 1778. He, Cornplanter, and John Butler led a force of about 450

Indians and 110 rangers to attack the Wyoming valley, Pa. The first two forts they approached surrendered but the third, Forty

Fort, refused to capitulate. On 3 July over 400 of its garrison marched out to challenge the attackers. After firing three

volleys the rebels were outflanked by the Native Americans and they panicked. Their retreat became a rout and more than 300

were killed. The Native American-loyalist force lost fewer than ten. The next day Forty Fort and the remaining stockades in

the valley surrendered. The eight forts and a thousand houses were burned but no civilians were harmed. Kaie˝├kwaahto˝ seems

to have spent September chasing a small rebel force under Colonel Thomas Hartley from Delaware country in the Susquehanna

valley. The rebels burned two Native Americans towns and the two sides subsequently fought at Wyalusing, Pa, with few casualties.

The Seneca chief did not participate in the other major military action of that year, the raid on Cherry Valley, NY. Late

in the summer of 1779 several thousand Continental soldiers under John Sullivan, supported by artillery, invaded the Iroquois

homeland. Butler, Brant, Kaie˝├kwaahto˝, and others marshalled a small force to oppose them. Butler and Brant advised harassing

the invaders while retreating slowly. Other, less wise, heads prevailed, and an attempt was made to block the enemy’s

path. The rebel artillery and a strategic blunder by the Native Americans led to a rout, and Sullivan proceeded to burn his

way through the Cayuga and Seneca country, devastating 40 villages including Ganundasaga. His army destroyed 160,000 bushels

of corn, “a vast quantity” of other vegetables, and extensive orchards. The agricultural base of the Native American

economy had been ravaged. With winter at hand the Iroquois, including Kaie˝├kwaahto˝, fled to Niagara to subsist on British

rations. Native Americans The devastation of their homeland did not break the spirit of the Senecas or their ancient chief.

He was on the war trail again in July and August 1780 as a leader in the expedition that destroyed the Canajoharie and Normans

Kill district, netting 50 or 60 prisoners. In October he was in the field again, joining Sir John Johnson* in a raid into

the Schoharie valley. He may have shared command with Brant of the force which during this expedition captured 56 rebels who

sallied forth from Fort Stanwix. The raiders also destroyed some 150,000 bushels of grain and burned 200 houses. In this same

year Kaie˝├kwaahto˝, his family, and others moved their homes to Buffalo Creek. They frequently visited the British posts

and on one of these occasions Kaie˝├kwaahto˝ paid his only documented visit to present-day Canada. It was reported that, after

being handsomely entertained by the officers at Fort Erie (Ont.), the family was in some danger as he attempted to manœuvre

his canoe back across the Niagara River. During the war Kaie˝├kwaahto˝ and his warriors had succeeded in pushing the white

frontier back almost as far as Albany but had in turn been driven from their homes to cluster about Niagara, the shores of

Lake Erie, and the Allegheny River. Britain, in negotiating a peace with the Americans, chose to ignore the Iroquois who had

fought at the side of her armies. A home on the Grand River (Ont.) for a portion of the Six Nations was obtained by Joseph

Brant. The Senecas for the most part did not follow the Mohawk chief but remained in what is now New York state to make their

own peace with the Americans. Abandoned by their British allies, they faced an aggressive and greedy American government in

negotiations at Fort Stanwix in 1784. Kaie˝├kwaahto˝ was not there; he was hunting. Perhaps he chose not to attend. He died

in 1786 on Smoke Creek. Years later, Governor Blacksnake recalled him: “he was pretty tall – over 6 feet –

& large in size – of a commanding figure. His eloquence was of a superior order – & in intellect he towered far

above his fellows; He fully enjoyed the confidence of his people.” From: historical accounts & records

In Native American diplomacy it was normal to return a captive or two as part of peace overtures. At the close of the uprising

Kaie˝├kwaahto˝ approached the Seneca family that had adopted Mary Jemison and stated that he was going to return her to the

authorities at Niagara. Her foster family hid her, however, and he went to Niagara empty handed. He later found another prisoner

to deliver to the British, and on 21 March 1764 he arrived with the captive at Johnson Hall (Johnstown, N.Y.). Four days after,

he addressed a conference there, using the usual metaphors to declare the coming of peace. The hatchet was buried and washed

by a stream to the ocean where it would be lost forever, and the dead on both sides were buried so that both British and Native

Americans could forget the conflict. Kaie˝├kwaahto˝’s name heads the list of Seneca chiefs on the preliminary articles

of peace signed on 3 April. He also played a role in the conference at Fort Stanwix (Rome, N.Y.) which in 1768 attempted to

draw a firm boundary between white settlement and Native American lands. Between the treaty of Fort Stanwix and the outbreak

of the American revolution, Kaie˝├kwaahto˝ remained in the background. He was seemingly of considerable influence among the

eastern Senecas, but the focus of diplomatic activity in Indian affairs was farther west. He appeared at Johnson Hall at least

twice in 1771 with news from the west, and when Guy Johnson succeeded to the post of superintendent of northern Native Americans

he apparently cultivated the friendship of Kaie˝├kwaahto˝ in particular. The outbreak of rebellion in the British colonies

gave the ageing chief another chance to exhibit his military prowess. When the Senecas and most of the other Six Nations decided

in the summer of 1777 to enter the war as allies of the British, he and Kaiũtwah├kũ (Cornplanter) were named to

lead the Senecas in the war. Since they had as many warriors as the rest of the Six Nations combined, Kaie˝├kwaahto˝ was to

play an important part in the conflict. Although his advanced years compelled him to ride a horse on military expeditions,

he was active throughout Native Americans under his command, and the British and loyalists with whom they cooperated, ran

up an impressive series of victories on the northern frontier. Full of energy, Kaie˝├kwaahto˝ immediately left the 1777 council

to harass Fort Stanwix, now a rebel-held post, which guarded the western entrance to the Mohawk valley. It was more than a

month before Barrimore Matthew St Leger’s force arrived and the siege began in earnest. The Indians had been invited

to smoke their pipes and watch their white allies take the fort, but on 5 August word arrived from Mary Brant [Ko˝watsi├tsiaiÚ˝ni]

that Brigadier-General Nicholas Herkimer and 800 Mohawk valley militia were advancing to raise the siege. The task of intercepting

them was delegated to the Indians and a small body of loyalist troops. Kaie˝├kwaahto˝, Cornplanter, and Joseph Brant [Thayendanegea*]

were all present to lead the Six Nations warriors. The engagement at nearby Oriskany proved one of the bloodiest of the war,

given the numbers involved. The rebels lost between 200 and 500 killed, and Native American losses were significant. Although

Herkimer’s force was practically exterminated, the lack of siege artillery doomed the British attempt to take the fort.

Kaie˝├kwaahto˝ was again on the war trail in the summer of 1778. He, Cornplanter, and John Butler led a force of about 450

Indians and 110 rangers to attack the Wyoming valley, Pa. The first two forts they approached surrendered but the third, Forty

Fort, refused to capitulate. On 3 July over 400 of its garrison marched out to challenge the attackers. After firing three

volleys the rebels were outflanked by the Native Americans and they panicked. Their retreat became a rout and more than 300

were killed. The Native American-loyalist force lost fewer than ten. The next day Forty Fort and the remaining stockades in

the valley surrendered. The eight forts and a thousand houses were burned but no civilians were harmed. Kaie˝├kwaahto˝ seems

to have spent September chasing a small rebel force under Colonel Thomas Hartley from Delaware country in the Susquehanna

valley. The rebels burned two Native Americans towns and the two sides subsequently fought at Wyalusing, Pa, with few casualties.

The Seneca chief did not participate in the other major military action of that year, the raid on Cherry Valley, NY. Late

in the summer of 1779 several thousand Continental soldiers under John Sullivan, supported by artillery, invaded the Iroquois

homeland. Butler, Brant, Kaie˝├kwaahto˝, and others marshalled a small force to oppose them. Butler and Brant advised harassing

the invaders while retreating slowly. Other, less wise, heads prevailed, and an attempt was made to block the enemy’s

path. The rebel artillery and a strategic blunder by the Native Americans led to a rout, and Sullivan proceeded to burn his

way through the Cayuga and Seneca country, devastating 40 villages including Ganundasaga. His army destroyed 160,000 bushels

of corn, “a vast quantity” of other vegetables, and extensive orchards. The agricultural base of the Native American

economy had been ravaged. With winter at hand the Iroquois, including Kaie˝├kwaahto˝, fled to Niagara to subsist on British

rations. Native Americans The devastation of their homeland did not break the spirit of the Senecas or their ancient chief.

He was on the war trail again in July and August 1780 as a leader in the expedition that destroyed the Canajoharie and Normans

Kill district, netting 50 or 60 prisoners. In October he was in the field again, joining Sir John Johnson* in a raid into

the Schoharie valley. He may have shared command with Brant of the force which during this expedition captured 56 rebels who

sallied forth from Fort Stanwix. The raiders also destroyed some 150,000 bushels of grain and burned 200 houses. In this same

year Kaie˝├kwaahto˝, his family, and others moved their homes to Buffalo Creek. They frequently visited the British posts

and on one of these occasions Kaie˝├kwaahto˝ paid his only documented visit to present-day Canada. It was reported that, after

being handsomely entertained by the officers at Fort Erie (Ont.), the family was in some danger as he attempted to manœuvre

his canoe back across the Niagara River. During the war Kaie˝├kwaahto˝ and his warriors had succeeded in pushing the white

frontier back almost as far as Albany but had in turn been driven from their homes to cluster about Niagara, the shores of

Lake Erie, and the Allegheny River. Britain, in negotiating a peace with the Americans, chose to ignore the Iroquois who had

fought at the side of her armies. A home on the Grand River (Ont.) for a portion of the Six Nations was obtained by Joseph

Brant. The Senecas for the most part did not follow the Mohawk chief but remained in what is now New York state to make their

own peace with the Americans. Abandoned by their British allies, they faced an aggressive and greedy American government in

negotiations at Fort Stanwix in 1784. Kaie˝├kwaahto˝ was not there; he was hunting. Perhaps he chose not to attend. He died

in 1786 on Smoke Creek. Years later, Governor Blacksnake recalled him: “he was pretty tall – over 6 feet –

& large in size – of a commanding figure. His eloquence was of a superior order – & in intellect he towered far

above his fellows; He fully enjoyed the confidence of his people.” From: historical accounts & records

|