|

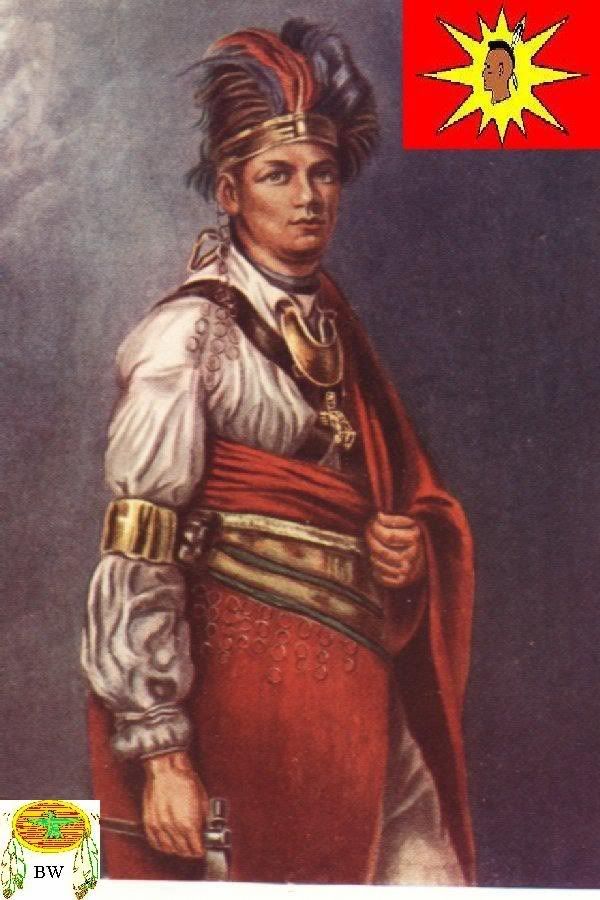

Thayendanegea

Chief Joseph Brant

(1742-1807)

Warriors Citation

Brant was born on the banks of the Ohio River and given the Indian name of Thayendanegea, meaning "he places two bets." He

inherited the status of Mohawk chief from his father. He attended Moor's Charity School for Native Americans in Lebanon, Connecticut,

where he learned to speak English and studied Western history and literature. He became an interpreter for an Anglican Missionary,

the Reverend John Stuart, and together they translated the prayer book and the Gospel of Mark into Mohawk. Molly Brant, Joseph's

sister, married General Sir William Johnson who was the British superintendent for northern Indian affairs. Sir William was

called to duty during the last French and Indian War of 1754-1763. Joseph followed Sir William into battle at the age of 13,

along with the other Native American braves at the school. Following this frightening experience, Joseph returned to school

for a short period. Sir William had need of an interpreter and aid in his business with the Indians and employed Joseph in

this prestigious position. In his work with Sir William, Joseph discovered a trading company that was buying discarded guns

from the Army, filling cracks in the barrels with lead, and then selling them to Native Americans. The guns would explode

when fired, often injuring the owner. Joseph was able to prove this in court and the trading company's license was revoked.

It was the custom for young men not to marry until they had made their mark, and Joseph was now prepared to choose a wife.

Around 1768 he married Christine, the daughter of an Oneida chief, whom he had met in school. They had both Native American

and Anglican wedding ceremonies and lived on a farm which Joseph had inherited. Christine died of tuberculosis around 1771,

leaving Joseph with a son and a daughter. During this time, Joseph resumed his religious work, translating the Acts of the

Apostles into the Mohawk language. In 1773, he married Susannah, sister of his first wife. Susannah died a few months later,

also of tuberculosis. In 1774 he was appointed secretary to Sir William's successor, Guy Johnson. In 1775 he received a captain's

commission and was sent to England to assess whether the British would or would not help the Mohawk recover their lands. He

met with the King on two occasions and a dinner was held in his honor. While in England, Brant attended a performance of Romeo

and Juliet. Lady Ossory, a member of a famous Irish family, asked him, "What do you think of that kind of love-making, Captain

Brant?" He replied, "There is too much of it, your ladyship." "Why do you say that?', and Joseph answered quickly, "Because,

your ladyship, no lover worth a lady's while would waste his time and breath in all that speech-making. If my people were

to make love in that way our race would be extinct in two generations." On his return to the colonies, he saw action in the

Battle of Long Island in August 1776. He led four of the six nations of the Iroquois League in attacks against colonial outposts

on the New York frontier. The Iroquois League was a confederation of upper New York State Native American tribes formed between

1570 and 1600 who called themselves "the people of the long house." Initially it was composed of the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga,

Cayuga, and Seneca. After the Tuscarora joined in 1722, the league became known to the English as the Six Nations and was

recognized as such in Albany, New York, in 1722. They were better organized and more effective, especially in warfare, than

other Native American confederacies in the region. As the longevity of this union would suggest, these Native Americans were

more advanced socially than is often thought. Benjamin Franklin even cited their success in his argument for the unification

of the colonies. They lived in comfortable homes, often better than those of the colonists, raised crops, and sent hunters

to Ohio to supply meat for those living back in New York. These hunters were usually young braves or young married couples,

as was the case with Joseph Brant's parents. During the U.S. War of Independence a split developed in the Iroquois League,

with the Oneida and Tuscarora favoring the American cause while the others fought for the British under the leadership of

Mohawk Chief Joseph Brant. A few of the leaders favored a neutral stance, preferring to let the white men kill each other

rather than become involved. Brant feared that the Native Americans would lose their lands if the colonists achieved independence.

Basic to animosities between Native Americans and whites was the difference in views over land ownership. The Native Americans

felt that the land was for the use of everyone and so initially saw no reason to not welcome the Europeans. The colonists,

on the other hand, were well acquainted with the privileges of ownership (or lack thereof) and were eager to acquire land

of their own. Brant commanded the Native Americans in the Battle of Oriskany on August 6, 1777. In early 1778 he gathered

a force of Indians from the villages of Unadilla and Oquaga on the Susquehanna River. On September 17, 1778 they destroyed

German Flats near Herkimer, New York. The patriots retaliated under the leadership of Col. William Butler and destroyed Unadilla

and Oquaga on October 8th and 10th. Brant's forces, along with loyalists under Capt. Walter N. Butler, then set out to destroy

the town and fort at Cherry Valley. There were 200-300 men stationed at the fort but they were unprepared for the attack on

August 11, 1778. The attackers killed some 30 men, women, and children, burned houses, and took 71 prisoners. They killed

16 soldiers at the fort but withdrew the following day when 200 patriot reinforcements arrived. The settlement was abandoned

and the event came to be known as the "Cherry Valley Massacre." Brant won a formidable reputation after this raid and in cooperation

with loyalists and British regulars; he brought fear and destruction to the entire Mohawk Valley, southern New York, and northern

Pennsylvania. He thwarted the attempts of a rival chief, Red Jacket, to persuade the Iroquois to make peace with the revolutionaries.

In 1779, U.S. Major General John Sullivan led a retaliatory expedition of 3700 men against the Iroquois, destroying fields,

orchards, granaries, and their morale. The Iroquois were defeated near present-day Elmira, N.Y. In spite of this, Native American

raids persisted until the end of the war and many homesteads had to abandoned. The Iroquois League came to an end after admitting

defeat in the Second Treaty of Ft. Stanwix in 1784. Around 1782, Brant married his third wife, Catherine Croghan, daughter

of an Irishman and a Mohawk. With the war over, and the British having surrendered lands to the colonists and not to the Native

Americans, Brant was faced with finding a new home for himself and his people. He discouraged further Indian warfare and helped

the U.S. commissioners to secure peace treaties with the Miamis and other tribes. He retained his commission in the British

Army and was awarded a grant of land on the Grand River in Ontario by Governor Sir Frederick Haldimand of Canada in 1784.

The tract of 675,000 acres encompassed the Grand River from its mouth to its source, six miles deep on either side. Brant

led 1843 Iroquois Loyalists from New York State to this site where they settled and established the Grand River Reservation

for the Mohawk. The party included members of all six tribes, but primarily Mohawk and Cayugas, as well as a few Delaware,

Nanticoke, Tutelo, Creek, and Cherokee, who had lived with the Iroquois before the war. They settled in small tribal villages

along the river. Sir Haldimand had hurriedly pushed through the land agreement before his term of office expired and was unable

to provide the Indians with legal title to the property. For this reason, Brant again traveled to England in 1785. He succeeded

in obtaining compensation for Mohawk losses in the U.S. War for Independence and received funds for the first Episcopal Church

in Upper Canada, but failed to obtain firm title to the Grand River reservation. The legality of the transfer remains under

question today. He felt that his followers could learn much from observing the ways of the white man and made a number of

land sales of reservation property to white settlers to this end, despite the unsettled ownership. He tried unsuccessfully

to arrange a settlement between the Iroquois and the United States. He traveled in the American West promoting an all-Native

American confederacy to resist land cessions. He was a man who studied and was able to internalize the better qualities of

the white man while always remaining loyal and devoted to his people. Joseph Brant died on the reservation. From: historical

accounts & records

LINK TO BRAVEHORSE WARRIORS VOLUME TWO

|