|

BRAVEHORSE WARRIOR Payipwat

Cree Warrior

Chief Payipwat

Warrior Citation

PAYIPWAT (Piapot, Hole in the Sioux, Kisikawasan, Flash in the Sky), Plains Cree chief; possibly b. c. 1816, probably in what

is now southwestern Manitoba or eastern Saskatchewan; d. in late April 1908 on the Piapot Reserve, Sask. Originally named

Kisikawasan, or Flash in the Sky, Payipwat was one of the five major leaders of the Plains Cree after 1860. While he was a

child he and his grandmother were taken prisoner by the Sioux. He grew to manhood among them and learned their medicine. In

the 1830s he was captured by the Cree and returned to his own people. Because he knew Sioux medicine, which the Cree believed

to be especially powerful, he was then given the name Payipwat, sometimes translated as “one who knows the secrets of

the Sioux.” By 1860 he had grown to be a highly respected spiritual leader among the Cree and chief of the Young Dogs,

a Cree band which had a large Assiniboin component and frequented Assiniboin territory. More completely than any other branch

of the Cree nation, the Young Dog band had adapted to the buffalo-hunting life of the plains. Its members were notorious as

horse thieves and warriors, and because they did little trading had a reputation with the Hudson’s Bay Company as troublemakers.

They were among the most feared of the Cree because they had made clear their resentment when in the 1850s the company and

the MÚtis moved into the upper Qu’Appelle River district to compete with the Cree for the diminishing herds of buffalo.

Since the buffalo were fast disappearing from Cree territory, Payipwat believed that his people were about to face a severe

crisis. He advocated that the Plains Cree expand west into the Cypress Hills, the last major buffalo range touching on Cree

lands and one of the last in British North America. Until 1860 the region (now in southwestern Saskatchewan and southeastern

Alberta) had been a borderland between the Sioux, Assiniboin, Blackfoot, Blood, and Cree. Because few Indian bands hunted

there, the area was a natural refuge for the buffalo. Payipwat and other Cree leaders determined to make it their territory.

Most of the Plains Cree nation took part in the invasion of the Cypress Hills. Although Payipwat played a major role, he refused

to participate in what is often regarded as the culmination, an attack on a Blood village near present-day Lethbridge, Alta,

late in 1870. The night before, he had a dream that he interpreted as portending disaster but he was unable to dissuade the

other leaders from their plan. In this “battle of Belly River,” as it has become known, the Cree lost about one-third

of their warriors. The outcome limited them to the eastern portion of the Cypress Hills. The Young Dogs, along with many other

Cree and Saulteaux from the Qu’Appelle River region, made that area their home, hunting as far south as the Milk River

district of Montana. As a result of their absence from Qu’Appelle, Payipwat was not informed of Canada’s intent

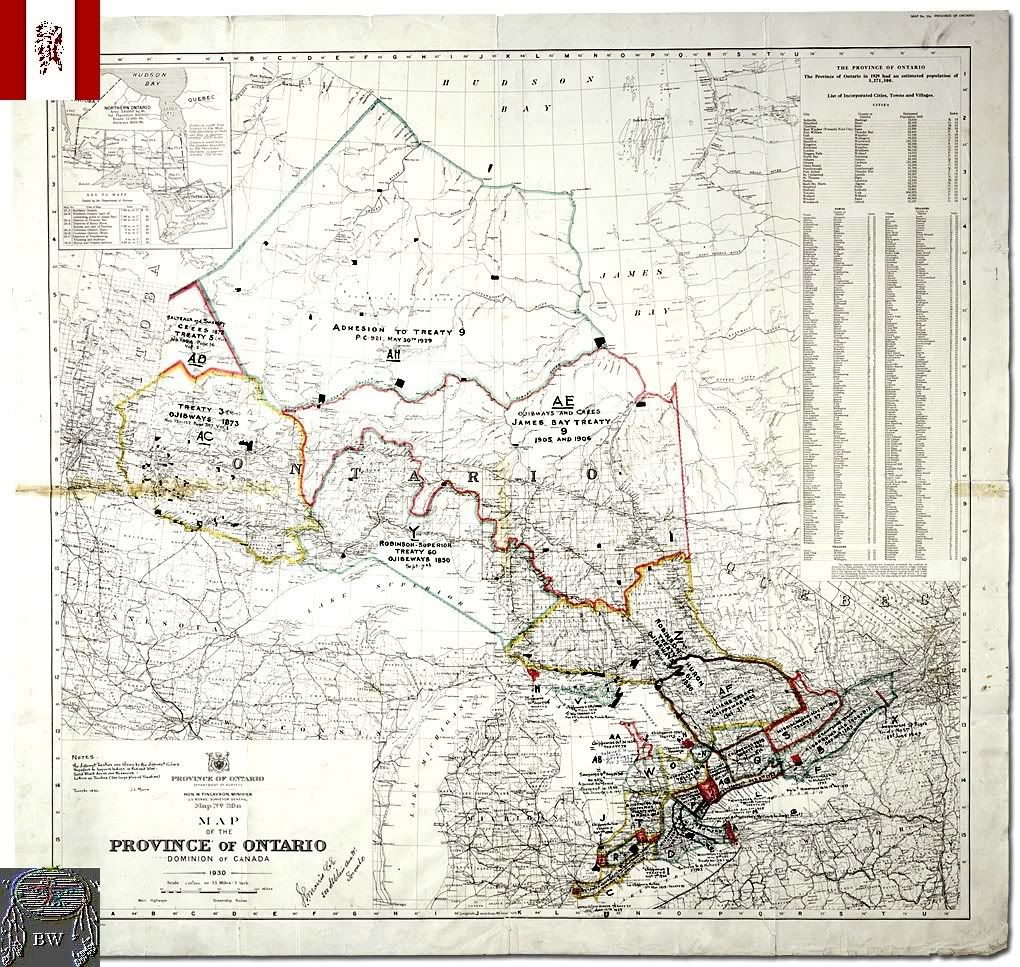

to send a commission that would speak to the Cree and Saulteaux people there. He learned of it only after an agreement, Treaty

No.4, had been negotiated in 1874. Payipwat and Cheekuk, the principal Saulteaux leader of the Qu’Appelle district,

met treaty commissioner William Joseph Christie in 1875 at the Qu’Appelle Lakes (The Fishing Lakes). They had with them

more than half the Native American people who lived in the region. Payipwat stated that he regarded what had taken place in

1874 as only a preliminary negotiation. To make sure that the Cree were provided with a base from which they could begin agriculture

with a reasonable chance of success, he stipulated that the final treaty had to make provision for farm instructors, mills,

forges, mechanics, more tools and machinery, and medical assistance. He was assured that these new demands would be forwarded

to Ottawa to determine whether they would be put into the treaty, and so on 9 Sept. 1875 he signed the “preliminary”

document of 1874.

Chief Payipwat

Warrior Citation

PAYIPWAT (Piapot, Hole in the Sioux, Kisikawasan, Flash in the Sky), Plains Cree chief; possibly b. c. 1816, probably in what

is now southwestern Manitoba or eastern Saskatchewan; d. in late April 1908 on the Piapot Reserve, Sask. Originally named

Kisikawasan, or Flash in the Sky, Payipwat was one of the five major leaders of the Plains Cree after 1860. While he was a

child he and his grandmother were taken prisoner by the Sioux. He grew to manhood among them and learned their medicine. In

the 1830s he was captured by the Cree and returned to his own people. Because he knew Sioux medicine, which the Cree believed

to be especially powerful, he was then given the name Payipwat, sometimes translated as “one who knows the secrets of

the Sioux.” By 1860 he had grown to be a highly respected spiritual leader among the Cree and chief of the Young Dogs,

a Cree band which had a large Assiniboin component and frequented Assiniboin territory. More completely than any other branch

of the Cree nation, the Young Dog band had adapted to the buffalo-hunting life of the plains. Its members were notorious as

horse thieves and warriors, and because they did little trading had a reputation with the Hudson’s Bay Company as troublemakers.

They were among the most feared of the Cree because they had made clear their resentment when in the 1850s the company and

the MÚtis moved into the upper Qu’Appelle River district to compete with the Cree for the diminishing herds of buffalo.

Since the buffalo were fast disappearing from Cree territory, Payipwat believed that his people were about to face a severe

crisis. He advocated that the Plains Cree expand west into the Cypress Hills, the last major buffalo range touching on Cree

lands and one of the last in British North America. Until 1860 the region (now in southwestern Saskatchewan and southeastern

Alberta) had been a borderland between the Sioux, Assiniboin, Blackfoot, Blood, and Cree. Because few Indian bands hunted

there, the area was a natural refuge for the buffalo. Payipwat and other Cree leaders determined to make it their territory.

Most of the Plains Cree nation took part in the invasion of the Cypress Hills. Although Payipwat played a major role, he refused

to participate in what is often regarded as the culmination, an attack on a Blood village near present-day Lethbridge, Alta,

late in 1870. The night before, he had a dream that he interpreted as portending disaster but he was unable to dissuade the

other leaders from their plan. In this “battle of Belly River,” as it has become known, the Cree lost about one-third

of their warriors. The outcome limited them to the eastern portion of the Cypress Hills. The Young Dogs, along with many other

Cree and Saulteaux from the Qu’Appelle River region, made that area their home, hunting as far south as the Milk River

district of Montana. As a result of their absence from Qu’Appelle, Payipwat was not informed of Canada’s intent

to send a commission that would speak to the Cree and Saulteaux people there. He learned of it only after an agreement, Treaty

No.4, had been negotiated in 1874. Payipwat and Cheekuk, the principal Saulteaux leader of the Qu’Appelle district,

met treaty commissioner William Joseph Christie in 1875 at the Qu’Appelle Lakes (The Fishing Lakes). They had with them

more than half the Native American people who lived in the region. Payipwat stated that he regarded what had taken place in

1874 as only a preliminary negotiation. To make sure that the Cree were provided with a base from which they could begin agriculture

with a reasonable chance of success, he stipulated that the final treaty had to make provision for farm instructors, mills,

forges, mechanics, more tools and machinery, and medical assistance. He was assured that these new demands would be forwarded

to Ottawa to determine whether they would be put into the treaty, and so on 9 Sept. 1875 he signed the “preliminary”

document of 1874.

Payipwat and his people mistakenly believed that the government had agreed to add his conditions to Treaty No.4. In fact,

it refused. Most of the terms did become part of Treaty No.6, negotiated in 1876 at forts Carlton and Pitt with the River,

House, and Willow branches of the Plains Cree. Moreover, from 1879 the government provided food and farming instruction, not

only to the people in Treaty No.6 but also to those in Treaty No.4. These events confirmed Payipwat in his belief that Treaty

No.4 had been modified. Because the government never did furnish all that he thought he had negotiated as part of the “Treaty

of 1875,” he maintained to his dying day that Ottawa had not fulfilled its promises. Throughout the 1870s and early

1880s Payipwat was in close contact with the leaders of the River people, Little Pine [Minahikosis] and Big Bear [Mistahimaskwa].

These northern leaders, who in the late 1870s were also living in the Cypress Hills, were much concerned that the treaties

with Canada would destroy Cree autonomy and culture. They refused to take treaty until clauses guaranteeing autonomy were

added and until the agreements made provision for a Cree territory rather than a number of isolated reserves. They believed

that a territory on which all the Plains Cree lived would give some protection from governmental interference. Payipwat became

the spokesperson among the southern Cree for this movement. He led the people of Treaty No.4 in calling for revisions to provide

such a homeland. When Ottawa proved reluctant, in 1879–80 Payipwat, Cowessess [Kiwis┘nce], another prominent leader

of the southern Cree, Foremost Man [Ne-can-nete], a minor Cree chief, and the entire Assiniboin nation requested reserves

next to one another in the Cypress Hills. The site Payipwat selected in May 1880 was some 37 miles north-northeast of Fort

Walsh, the North-West Mounted Police post there. Little Pine and the part of Big Bear’s band that had taken treaty in

1879 under Lucky Man [Papewes] asked for reserves contiguous to either Payipwat’s or the Assiniboin. Ottawa agreed and

had the Assiniboin reserve surveyed in 1880. The Native American people were creating a territory that would keep the Assiniboin

and Plains Cree united and would enable them to protect their autonomy. What Ottawa declined to do de jure in the treaties

was being done de facto by the people in the Cypress Hills. Their efforts were frustrated by Native American commissioner

Edgar Dewdney. By 1881 he was aware that the huge concentration of Native Americans had made them an autonomous political

entity which neither the police nor the government could control. He believed that he could use the starvation which the people

were experiencing with the disappearance of the buffalo to force acceptance of the treaties as written and to prevent the

creation of an Indian territory. He was helped, unwittingly, by the Young Dogs and other Cree. In 1881, when they went to

the remaining buffalo ranges in Montana, they stole horses from the Crow there and allegedly killed cattle for food. The American

Army rounded up the Cree, confiscated their guns and wagons, and escorted them back to Canada. Once they were effectively

disarmed, Dewdney seized the opportunity. He recommended the closing of Fort Walsh in 1882 and stopped issuing rations until

the Cree and the Assiniboin gave up their requests for reserves in the hills and moved north. Payipwat and the Young Dogs

agreed in 1882 to go to the Qu’Appelle River and they were given horses, wagons, and rations for the journey. They did

not remain long in the Qu’Appelle region, however. Payipwat claimed to be poorly treated since he was denied what he

thought he and his people were entitled to by treaty. He and his Young Dogs returned to the Cypress Hills in September and

wintered with Big Bear and Little Pine. The commissioner of the NWMP, Acheson Gosford Irvine, feared violence against the

police and attacks on the construction crews of the Canadian Pacific Railway if the Cree were left to starve. He ignored instructions

from Ottawa, kept Fort Walsh open, and fed the Cree. By the spring of 1883 Ottawa had expanded the NWMP. It ordered Irvine

to shut down the fort and end rations to Payipwat and the Cree in the Cypress Hills. Weakened by starvation, Payipwat agreed

to move to Indian Head and take a reserve beside the Assiniboin, who had moved there early in 1882. To make sure that he actually

left, a police escort accompanied him. This event may be the origin of the legendary story of how three police officers kicked

down Payipwat’s tepee around him when he attempted to stop construction of the CPR. There is no other record of the

police escorting him anywhere, nor is there any mention in the files of the Department of Native American Affairs and the

NWMP of an effort by Payipwat to stop the railway or of the police dealing with him on a railway issue. Payipwat was no sooner

out of the Cypress Hills than he attempted to effect a concentration of Native Americans elsewhere in the Treaty No.4 area.

He had originally intended to do so near Indian Head, where he selected a reserve site, but because of the lack of fresh food

many of his people died there during the winter of 1883–84. The band, which had numbered over 700 people in 1878, declined

to 450 members by 1884. In April that year Payipwat declared that he was moving to the neighbourhood of Fort Qu’Appelle

and taking a reserve next to Paskw┘w’s. He also announced that, in preparation, he intended to hold at Paskw┘w’s

a Thirst Dance and general council of all the Indian leaders of the Treaty No.4 region. He invited Dewdney to the council

to discuss treaty revision, but Dewdney refused to attend. He feared that Payipwat was working on a coalition that would promote

the establishment of a Native American territory. He therefore sent NWMP commissioner Irvine after Payipwat with orders to

break up the council and force him back to Indian Head. Irvine, with 56 men and a seven-pounder gun, caught up with Payipwat

in early May 1884, shortly before he reached Paskw┘w’s reserve. When he attempted to arrest the Cree leader in the middle

of the night, he found his force surrounded by armed warriors. Rather than risk a battle, he negotiated with Payipwat. Hayter

Reed, representing the Native American commissioner’s office, was present at the talks and was persuaded by Irvine that

Payipwat should be permitted to take a reserve beside Paskw┘w’s and that the Thirst Dance and council should be allowed

to proceed. Dewdney came to believe that unless Payipwat was permitted to settle near Fort Qu’Appelle he would move

to the Battleford area and take a reserve next to Little Pine. If that should happen, other Cree from the Treaty No.4 region

would follow and Ottawa would be faced in the Battleford district with the Native American coalition and territory that had

been so narrowly averted in the Cypress Hills. Dewdney was aware that the movement for treaty revision was growing in strength.

Little Pine and Big Bear were promoting the plan among the people of Treaty No.6 while Payipwat was encouraging the Assiniboin,

the Saulteaux, and the Touchwood Hills and Rabbit Skin people of the Cree to join him in seeking to have Treaty No.4 modified.

Just when it appeared that the movement was on the verge of success, it was destroyed. The government was able to take advantage

of the MÚtis rebellion of 1885 [see Louis Riel] to put an end to it. A major military base was established next to Payipwat’s

reserve, which was officially surveyed in June 1885. By labelling his associates as rebels, the authorities could use the

troops to attack them and bring them to trial as traitors. A brief jail term served to destroy the health of Big Bear and,

since Little Pine had died in the spring of 1885, Payipwat was the only leader of the revision movement to survive. He was

held in check, first by the troops stationed near his reserve and then by the close surveillance the NWMP kept on him. Recognized

as the major Cree spiritual leader in the south, Payipwat continued to be distrusted by Ottawa in the post-rebellion years

since he persisted in promoting Indian culture and was able to make his reserve a homeland for his people. He was feared because

of his former contacts with the Sioux and his knowledge of Sioux medicine. The authorities were concerned that he would use

his influence to have the Cree participate in the Messiah and Ghost Dance movement that caused so much difficulty on the Sioux

reservations in the United States [ Tatanka I-yotank*]. There is, however, no conclusive evidence that he was involved in

this movement. Payipwat came to be regarded as the spokesperson for the traditionalists among the Cree. On his reserve he

was able to prevent the government from breaking up the village, the customary form of social organization among the Plains

Cree. Ottawa had wanted to atomize the Young Dog band by making its members settle on individual farms scattered over the

54-square-mile reserve. Payipwat refused to allow the land to be surveyed into the 40-acre parcels that would have enabled

the government to force the dispersal of the band’s members. As long as he lived, his people resided in the village

and practised the Thirst Dance and the Give Away Dance, even though these ceremonies were outlawed in 1892. During the 1890s

another 7 square miles was added to the reserve, but it remained well short of the 110 square miles to which the band was

entitled by treaty, and to this date there is an outstanding land claim against the Canadian government. The old leader came

under a good deal of pressure after 1900. A new Indian agent, William Morris Graham, was determined to destroy him and ruin

the Native American homeland he had maintained on his reserve. Graham demanded that he be deposed as chief on the grounds

of incompetence. In 1902 he had Payipwat arrested for interfering with a policeman engaged in apprehending a suspect on the

reserve. When Native American commissioner David Laird, who had known Payipwat since the 1870s, refused to recognize his behaviour

as sufficient grounds for deposition, Graham wanted Payipwat arrested for holding a Thirst Dance. These were better grounds

for an attack on his authority. Ottawa deposed Payipwat on 15 April 1902. “I have no doubt he has been too harshly dealt

with,” commented Governor General Lord Minto [Elliot], who met him in September and who tried unsuccessfully to have

the ban on dances lifted. “He had been a celebrated old chief for many years – and a great warrior in his time.”

Payipwat died on his reserve late in April 1908. From: historical accounts & records

Payipwat and his people mistakenly believed that the government had agreed to add his conditions to Treaty No.4. In fact,

it refused. Most of the terms did become part of Treaty No.6, negotiated in 1876 at forts Carlton and Pitt with the River,

House, and Willow branches of the Plains Cree. Moreover, from 1879 the government provided food and farming instruction, not

only to the people in Treaty No.6 but also to those in Treaty No.4. These events confirmed Payipwat in his belief that Treaty

No.4 had been modified. Because the government never did furnish all that he thought he had negotiated as part of the “Treaty

of 1875,” he maintained to his dying day that Ottawa had not fulfilled its promises. Throughout the 1870s and early

1880s Payipwat was in close contact with the leaders of the River people, Little Pine [Minahikosis] and Big Bear [Mistahimaskwa].

These northern leaders, who in the late 1870s were also living in the Cypress Hills, were much concerned that the treaties

with Canada would destroy Cree autonomy and culture. They refused to take treaty until clauses guaranteeing autonomy were

added and until the agreements made provision for a Cree territory rather than a number of isolated reserves. They believed

that a territory on which all the Plains Cree lived would give some protection from governmental interference. Payipwat became

the spokesperson among the southern Cree for this movement. He led the people of Treaty No.4 in calling for revisions to provide

such a homeland. When Ottawa proved reluctant, in 1879–80 Payipwat, Cowessess [Kiwis┘nce], another prominent leader

of the southern Cree, Foremost Man [Ne-can-nete], a minor Cree chief, and the entire Assiniboin nation requested reserves

next to one another in the Cypress Hills. The site Payipwat selected in May 1880 was some 37 miles north-northeast of Fort

Walsh, the North-West Mounted Police post there. Little Pine and the part of Big Bear’s band that had taken treaty in

1879 under Lucky Man [Papewes] asked for reserves contiguous to either Payipwat’s or the Assiniboin. Ottawa agreed and

had the Assiniboin reserve surveyed in 1880. The Native American people were creating a territory that would keep the Assiniboin

and Plains Cree united and would enable them to protect their autonomy. What Ottawa declined to do de jure in the treaties

was being done de facto by the people in the Cypress Hills. Their efforts were frustrated by Native American commissioner

Edgar Dewdney. By 1881 he was aware that the huge concentration of Native Americans had made them an autonomous political

entity which neither the police nor the government could control. He believed that he could use the starvation which the people

were experiencing with the disappearance of the buffalo to force acceptance of the treaties as written and to prevent the

creation of an Indian territory. He was helped, unwittingly, by the Young Dogs and other Cree. In 1881, when they went to

the remaining buffalo ranges in Montana, they stole horses from the Crow there and allegedly killed cattle for food. The American

Army rounded up the Cree, confiscated their guns and wagons, and escorted them back to Canada. Once they were effectively

disarmed, Dewdney seized the opportunity. He recommended the closing of Fort Walsh in 1882 and stopped issuing rations until

the Cree and the Assiniboin gave up their requests for reserves in the hills and moved north. Payipwat and the Young Dogs

agreed in 1882 to go to the Qu’Appelle River and they were given horses, wagons, and rations for the journey. They did

not remain long in the Qu’Appelle region, however. Payipwat claimed to be poorly treated since he was denied what he

thought he and his people were entitled to by treaty. He and his Young Dogs returned to the Cypress Hills in September and

wintered with Big Bear and Little Pine. The commissioner of the NWMP, Acheson Gosford Irvine, feared violence against the

police and attacks on the construction crews of the Canadian Pacific Railway if the Cree were left to starve. He ignored instructions

from Ottawa, kept Fort Walsh open, and fed the Cree. By the spring of 1883 Ottawa had expanded the NWMP. It ordered Irvine

to shut down the fort and end rations to Payipwat and the Cree in the Cypress Hills. Weakened by starvation, Payipwat agreed

to move to Indian Head and take a reserve beside the Assiniboin, who had moved there early in 1882. To make sure that he actually

left, a police escort accompanied him. This event may be the origin of the legendary story of how three police officers kicked

down Payipwat’s tepee around him when he attempted to stop construction of the CPR. There is no other record of the

police escorting him anywhere, nor is there any mention in the files of the Department of Native American Affairs and the

NWMP of an effort by Payipwat to stop the railway or of the police dealing with him on a railway issue. Payipwat was no sooner

out of the Cypress Hills than he attempted to effect a concentration of Native Americans elsewhere in the Treaty No.4 area.

He had originally intended to do so near Indian Head, where he selected a reserve site, but because of the lack of fresh food

many of his people died there during the winter of 1883–84. The band, which had numbered over 700 people in 1878, declined

to 450 members by 1884. In April that year Payipwat declared that he was moving to the neighbourhood of Fort Qu’Appelle

and taking a reserve next to Paskw┘w’s. He also announced that, in preparation, he intended to hold at Paskw┘w’s

a Thirst Dance and general council of all the Indian leaders of the Treaty No.4 region. He invited Dewdney to the council

to discuss treaty revision, but Dewdney refused to attend. He feared that Payipwat was working on a coalition that would promote

the establishment of a Native American territory. He therefore sent NWMP commissioner Irvine after Payipwat with orders to

break up the council and force him back to Indian Head. Irvine, with 56 men and a seven-pounder gun, caught up with Payipwat

in early May 1884, shortly before he reached Paskw┘w’s reserve. When he attempted to arrest the Cree leader in the middle

of the night, he found his force surrounded by armed warriors. Rather than risk a battle, he negotiated with Payipwat. Hayter

Reed, representing the Native American commissioner’s office, was present at the talks and was persuaded by Irvine that

Payipwat should be permitted to take a reserve beside Paskw┘w’s and that the Thirst Dance and council should be allowed

to proceed. Dewdney came to believe that unless Payipwat was permitted to settle near Fort Qu’Appelle he would move

to the Battleford area and take a reserve next to Little Pine. If that should happen, other Cree from the Treaty No.4 region

would follow and Ottawa would be faced in the Battleford district with the Native American coalition and territory that had

been so narrowly averted in the Cypress Hills. Dewdney was aware that the movement for treaty revision was growing in strength.

Little Pine and Big Bear were promoting the plan among the people of Treaty No.6 while Payipwat was encouraging the Assiniboin,

the Saulteaux, and the Touchwood Hills and Rabbit Skin people of the Cree to join him in seeking to have Treaty No.4 modified.

Just when it appeared that the movement was on the verge of success, it was destroyed. The government was able to take advantage

of the MÚtis rebellion of 1885 [see Louis Riel] to put an end to it. A major military base was established next to Payipwat’s

reserve, which was officially surveyed in June 1885. By labelling his associates as rebels, the authorities could use the

troops to attack them and bring them to trial as traitors. A brief jail term served to destroy the health of Big Bear and,

since Little Pine had died in the spring of 1885, Payipwat was the only leader of the revision movement to survive. He was

held in check, first by the troops stationed near his reserve and then by the close surveillance the NWMP kept on him. Recognized

as the major Cree spiritual leader in the south, Payipwat continued to be distrusted by Ottawa in the post-rebellion years

since he persisted in promoting Indian culture and was able to make his reserve a homeland for his people. He was feared because

of his former contacts with the Sioux and his knowledge of Sioux medicine. The authorities were concerned that he would use

his influence to have the Cree participate in the Messiah and Ghost Dance movement that caused so much difficulty on the Sioux

reservations in the United States [ Tatanka I-yotank*]. There is, however, no conclusive evidence that he was involved in

this movement. Payipwat came to be regarded as the spokesperson for the traditionalists among the Cree. On his reserve he

was able to prevent the government from breaking up the village, the customary form of social organization among the Plains

Cree. Ottawa had wanted to atomize the Young Dog band by making its members settle on individual farms scattered over the

54-square-mile reserve. Payipwat refused to allow the land to be surveyed into the 40-acre parcels that would have enabled

the government to force the dispersal of the band’s members. As long as he lived, his people resided in the village

and practised the Thirst Dance and the Give Away Dance, even though these ceremonies were outlawed in 1892. During the 1890s

another 7 square miles was added to the reserve, but it remained well short of the 110 square miles to which the band was

entitled by treaty, and to this date there is an outstanding land claim against the Canadian government. The old leader came

under a good deal of pressure after 1900. A new Indian agent, William Morris Graham, was determined to destroy him and ruin

the Native American homeland he had maintained on his reserve. Graham demanded that he be deposed as chief on the grounds

of incompetence. In 1902 he had Payipwat arrested for interfering with a policeman engaged in apprehending a suspect on the

reserve. When Native American commissioner David Laird, who had known Payipwat since the 1870s, refused to recognize his behaviour

as sufficient grounds for deposition, Graham wanted Payipwat arrested for holding a Thirst Dance. These were better grounds

for an attack on his authority. Ottawa deposed Payipwat on 15 April 1902. “I have no doubt he has been too harshly dealt

with,” commented Governor General Lord Minto [Elliot], who met him in September and who tried unsuccessfully to have

the ban on dances lifted. “He had been a celebrated old chief for many years – and a great warrior in his time.”

Payipwat died on his reserve late in April 1908. From: historical accounts & records

|