|

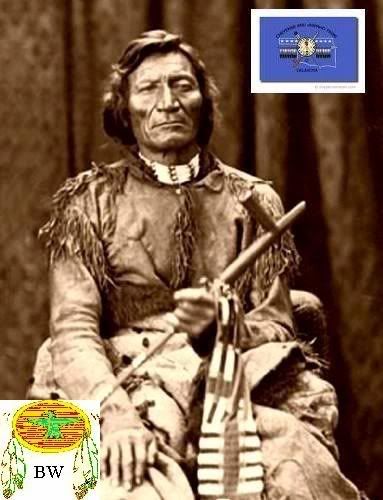

Chief Dull Knife

(1810-1883)

Warriors Citation

Although Dull Knife was active in the Cheyenne-Arapaho War in Colorado, the Sioux Wars for the Northern Plains, and also the

War for the Black Hills, he is, perhaps, best remembered for attempting to lead nearly three hundred people from an assigned

reservation back to their Tongue River homeland in northern Wyoming and southern Montana. Best-known for leading his people

in a courageous attempt to return from exile in Oklahoma to their Montana homeland in 1878, the Northern Cheyenne leader Morning

Star was born in about 1810 on the Rosebud River. He was known mostly by his nickname of Dull Knife, given to him by his brother-in-law,

who teased him about not having a sharp knife. A renowned Dog Soldier in his youth, Dull Knife became a member of the Council

of 44 and in the 1870s was one of the four principal, or Old Man, Chiefs. These chiefs represented the mystical four Sacred

Persons who dwelt at the cardinal points of the universe and were the guardians of creation. Little is known of Dull Knife's

early life. When he was a young man in the late 1820s, he went on a raiding party against the Pawnees. Capturing a young girl,

he saved her life by asking that she replace a member of his family previously lost to the Pawnees. When he became a chief,

Dull Knife made Little Woman his second wife, the union producing four daughters. Dull Knife had two other wives, Goes to

Get a Drink, with whom he had two daughters, and her sister Slow Woman, by whom he had four sons and another daughter. Dull

Knife first appears in white history in 1866, when he joined Red Cloud and the Oglala Sioux in ambushing U.S. soldiers under

Captain William J. Fetterman traveling along the Bozeman Trail to reach the Montana gold fields. At the end of the Bozeman

Trail War, the Northern Cheyennes signed the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie agreeing to settle on a reservation. The U.S. government

gave them the choice of joining the Crows in Montana, the Sioux in Dakota, or the Southern Cheyennes and Arapahos in Native

American Territory.

To force an early decision, the government withheld supplies, and the Northern Cheyennes signed an agreement on November 12,

1874, to move to Native American Territory whenever the U.S. government saw fit. These arrangements were set aside, however,

when the Black Hills Gold Rush led to war with the Sioux and their allies. The precipitating act was an ultimatum ordering

the Native Americans to return to agencies in South Dakota by January 31, 1876. The Big Horn Expedition, intended to force

the Native American s back to their agencies, engaged the Sioux, Northern Cheyennes, and Northern Arapahos in several major

battles, the most famous being Custer's fight on the Little Big Horn. Dull Knife was not in the Native American village that

day, but his son Medicine Lodge was present and died in combat against the Seventh Cavalry. The pivotal battle for the Northern

Cheyennes occurred on the morning of November 25, 1876, when Colonel Ronald Mackenzie's force of 600 men of the 4th Cavalry

and about 400 Native American scouts surprised Dull Knife's camp on the Red Forks of the Powder River. Reportedly killed in

the fighting were one of Dull Knife's sons and a son-in-law. The dead numbered around 40, but destruction of the village and

its contents sealed their fate. For all practical purposes, the campaign of 1876-77 ended the Native American wars on the

Northern Plains. Concern for their children caused Dull Knife and his people to surrender to the troops under Crook and Mackenzie

in the spring of 1877. At Fort Robinson they learned that the government had decreed that all Northern Cheyennes would be

sent to Native American Territory. Dull Knife and Little Wolf urged their tribesmen to abide by the wishes of the government.

The Northern Cheyennes may have been led to believe that they could return to their tribal lands in a year if they did not

like life in the south. The journey to Indian Territory began on May 28, 1877. In the group were 937 Northern Cheyennes. Seventy

days later, on August 5, they arrived at the Cheyenne and Arapaho Agency, selecting a campsite about eight miles north. Within

a year, the Northern Cheyennes were ready to return to their homeland. Starved, ravaged by disease, preyed upon white gangs

of horse thieves, unwilling to farm, critical of the civilized ways of their southern brethren, rankled by the fact that the

Northern Arapahos had been allowed to remain in the north, and with 50 of their children dead, they had had enough. From:

historical accounts & records

LINK TO BRAVEHORSE WARRIORS VOLUME TWO

|