|

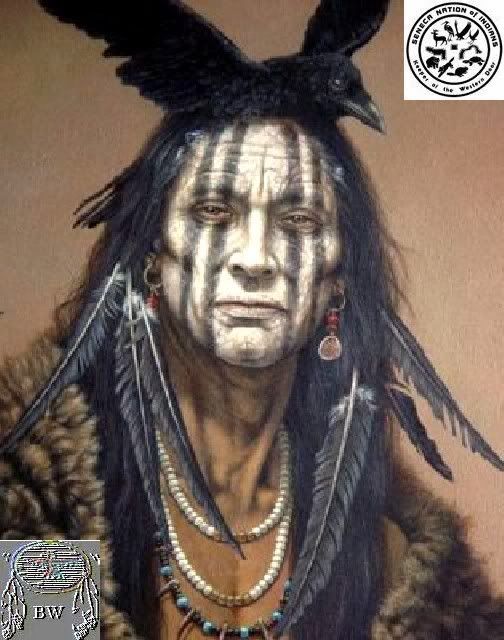

BRAVEHORSE WARRIOR Kayahsotaa

Seneca Warrior

Chief Kayahsotaa

Warrior Citation

KAYAHSOTA├ (written Gaiachoton, Geyesutha, Guyasuta, Kayashoton, Kiashuta, Quiasutha), Seneca chief and diplomat; b. c. 1725,

probably on the Genesee River (N.Y.), but his family moved to the Ohio region when he was young; d. on the Cornplanter Grant

(near Corydon, Pa), probably in 1794. His name, spelled Kayahsota├ according to Wallace L. Chafe’s phonemic orthography

of modern Seneca, means it stands up (or sets up) the cross. Although the Iroquois Confederacy had since 1701 been officially

committed to neutrality in the wars between the French and the British, the Iroquois of the Ohio country and the Senecas whose

homes were on the Genesee tended to pursue a pro-French policy. The French strengthened their position in the region in the

early 1750s by building a string of forts from Lake Erie to the forks of the Ohio [Paul Marin de La Malgue]. The British responded

in 1753 by sending the young George Washington to demand that the French withdraw from the area, which both powers claimed.

Years later, Washington remembered Kayahsota├ as being among the Indian escort on his fruitless journey. In 1755 Major-General

Edward Braddock attempted to capture Fort Duquesne (Pittsburgh, Pa), and Kayahsota├ was part of the force of French and Native

Americans which met and, under Jean-Daniel Dumas, routed him. In the autumn Kayahsota├ led a delegation of 20 Senecas to confer

with Governor Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil in Montreal.

Chief Kayahsotaa

Warrior Citation

KAYAHSOTA├ (written Gaiachoton, Geyesutha, Guyasuta, Kayashoton, Kiashuta, Quiasutha), Seneca chief and diplomat; b. c. 1725,

probably on the Genesee River (N.Y.), but his family moved to the Ohio region when he was young; d. on the Cornplanter Grant

(near Corydon, Pa), probably in 1794. His name, spelled Kayahsota├ according to Wallace L. Chafe’s phonemic orthography

of modern Seneca, means it stands up (or sets up) the cross. Although the Iroquois Confederacy had since 1701 been officially

committed to neutrality in the wars between the French and the British, the Iroquois of the Ohio country and the Senecas whose

homes were on the Genesee tended to pursue a pro-French policy. The French strengthened their position in the region in the

early 1750s by building a string of forts from Lake Erie to the forks of the Ohio [Paul Marin de La Malgue]. The British responded

in 1753 by sending the young George Washington to demand that the French withdraw from the area, which both powers claimed.

Years later, Washington remembered Kayahsota├ as being among the Indian escort on his fruitless journey. In 1755 Major-General

Edward Braddock attempted to capture Fort Duquesne (Pittsburgh, Pa), and Kayahsota├ was part of the force of French and Native

Americans which met and, under Jean-Daniel Dumas, routed him. In the autumn Kayahsota├ led a delegation of 20 Senecas to confer

with Governor Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil in Montreal.

The fortunes of war turned against the French and their native allies, and despite the assistance given by Kayahsota├ and

other western Senecas, in 1758 Fort Duquesne fell to the British under John Forbes. The French effectively withdrew from the

west in 1759, but hostilities were not at an end. The miserly attitude adopted by Amherst with respect to Native American

presents aggravated the difficulties between the native population and the British, and the result was the outbreak generally

known as the Pontiac rebellion, although it has been called the Kiyasuta and Pontiac war. Political leaders in the egalitarian

societies found in most of North America prior to its conquest by the white man lacked the authority to compel their constituents

to action and relied instead upon suasion. As he had no power to dictate public policy, and only his personal diplomatic skills

to shape public opinion, Kayahsota├ would not seem to merit a major share of the blame, or praise, for the conflict which

flared on the western frontier in 1763. The native population was nearly unanimous with respect to the desirability of attacking

the red-coated troops who had so recently replaced the French in that region, but Kayahsota├ was influential in focusing resentment

and was among the first to urge the use of force. As early as 1761 he and his fellow Seneca Tahahaiadoris were circulating

a large red wampum belt, known as the war hatchet, among the native population clustered about Detroit. According to Sir William

Johnson’s deputy, George Croghan, they privately admitted to him that the purpose was to bring on a general uprising

from Detroit to the Mohawk valley. Sir William himself came to Detroit in September 1761 to counteract their efforts. At the

conference Kayahsota├ denied the charges made against him but found himself contradicted by a Wyandot, and the resulting uproar

was calmed only by the efforts of Johnson. Later an Ottawa speaker, MÚcatÚpilÚsis, publicly identified Kayahsota├ as “the

bad Bird lately Amongst us.” Johnson met with Kayahsota├ privately and tried to convince the Seneca leader of the error

of his ways, but his diplomacy obtained only a brief respite. In June 1763 the frontier erupted in a general war. Most of

the Six Nations, including the eastern Senecas, remained at peace, but the western Senecas were active against the British.

Kayahsota├ and a few other Senecas fought alongside the Delawares in the siege of Fort Pitt (formerly Fort Duquesne) and against

the relief force under Colonel Henry Bouquet. Native testimony also suggests that he took part in the capture of the British

post at Venango (Franklin, Pa). After the fighting had run its course, Kayahsota├ was among those who signed a preliminary

peace agreement on 12 Aug. 1764, and he was given the task of carrying the conditions of peace to those groups still at war.

At the end of October 1764 Kayahsota├ came to Tuscarawas (near Bolivar, Ohio) with delegates of the Delawares, Shawnees, and

Senecas to meet with Bouquet. Bouquet’s major concern by this time was the release of white captives still in Native

American hands. He reported the negotiations a success, despite the necessity of dispatching Kayahsota├ to the Delawares to

protest the murder of a British soldier. Over 200 white captives were released (although some proved so reluctant to rejoin

white society that Bouquet had to post guards to prevent them from returning to their native captors). Following the conference,

Bouquet sent Kayahsota├ to fetch white captives held by the Wyandots. In the spring of 1765 George Croghan met with the western

Indians at Fort Pitt, and the return of prisoners was again a central issue. Kayahsota├ was there and was appointed a delegate

to yet another conference, this time with Sir William Johnson at Johnson Hall (Johnstown, NY). Kayahsota├ and other western

Indians met there from 4 to 13 July to negotiate a final peace. On the last day Kayahsota├ affixed the sign of a wolf, the

eponym of his clan, to the treaty. In the following decade Kayahsota├ served continually as an intermediary between the British

authorities and the native inhabitants of the Ohio region. Frequently journeying between Johnson Hall and the Ohio, he carried

wampum belts and Johnson’s words in attempts to preserve peace in the west or to isolate diplomatically such uncooperative

groups as the Shawnees. The Native American superintendent considered him a “Chief of much Capacity and vast Influence”

and found him “very useful on such Occasions.” When a group of Shawnees appeared at Fort Pitt in the spring of

1773 with a complaint about Virginia surveyors, it was Kayahsota├ who received them and presented them with a wampum belt.

On the other hand the western Native Americans often conveyed their grievances to Johnson through him. For example, the participants

in a major conference held at Fort Pitt in October 1773 sent Kayahsota├ to Johnson Hall with their complaints about unregulated

trade, particularly in liquor. Kayahsota├ was never able to carry out one of Johnson’s major aims, the removal of the

Mingos, Iroquois emigrants to the Ohio country, back to their old homes in what is now upstate New York. The superintendent

feared that these warriors, far from the moderating influence of the Onondaga council and even farther from Johnson Hall,

and carrying with them the well-earned reputation that the Iroquois enjoyed as fighting men, might join their Algonkian speaking

neighbors against the British. Johnson had first asked Kayahsota├ to persuade the Mingos to return in 1765, and the Seneca

chief was still trying unsuccessfully to carry out the policy in 1773. In addition to all his diplomatic activity, Kayahsota├

found time to work for various whites in the Ohio valley. His knowledge of the geography and the inhabitants of the region

enabled him to serve as guide and intermediary for travellers and traders. His duties took him several times to Fort de Chartres

(near Prairie du Rocher) in the Illinois country. When the American revolution broke out, Kayahsota├ had already established

a close working relationship with Guy Johnson, successor to Sir William as Native American superintendent. The rebels, however,

were active in courting the chief’s favor. Kayahsota├ was among the Indian leaders meeting representatives of the Continental

Congress at Fort Pitt in October 1775. He agreed that the Shawnees should surrender prisoners and booty captured in their

war with Virginia, which had just concluded, and consented to go to their towns to make sure the surrender was carried out.

In return, he asked for assurance that the boundary of white settlement established by the treaty of Fort Stanwix (1768) would

be honoured. He also observed astutely that disputes among the rebel representatives might well inhibit the kindling of a

bright council fire so necessary for effective Indian-white communication. The Six Nations held a neutral stance during the

early years of the American revolution. Kayahsota├ moved freely between the rebel post at Fort Pitt and the loyalist stronghold

at Niagara (near Youngstown, N.Y.). To the commandants at both forts he proclaimed the determination of the Six Nations to

take no part in any war between Britain and the colonies. At Fort Pitt on 6 July 1776 he emphasized native opposition to the

movement through Indian lands by armies of either side. Later, he went on an embassy to the Mingos to bring them into line

with the neutral position assumed by the other western tribes. In recognition of his services, the Continental Congress awarded

him a colonel’s commission and a silver gorget. It was inevitable, however, that the native population would eventually

enter the contest on the side of the crown. There were too many grievances against the encroaching Americans and, although

the war disrupted normal economic life, an active role in the conflict promised ample material rewards. With the decision

of the Six Nations in the summer of 1777 to abandon neutrality, Kayahsota├ began to work actively for the royal, and Indian,

cause. Later in the summer he was one of a large body of Indians who accompanied Barrimore Matthew St Leger against the rebels

at Fort Stanwix (Rome, N.Y.). The siege of this fort at the western end of the Mohawk valley was in its initial phase when

word came from Mary Brant [Ko˝watsi├tsiaiÚ˝ni] that 800 militiamen were marching to attack the besiegers. It was primarily

the Indians who were dispatched to meet them, and the rebels were repulsed in the bloody battle of Oriskany nearby. Kayahsota├

was in the field again soon; in December 1777 Simon Girty* reported that the Seneca chief or members of his war party had

killed four people near Ligonier, Pa. When in 1779 a rebel army commanded by Daniel Brodhead marched from Fort Pitt up the

Allegheny river valley, burning Seneca villages, Kayahsota├ appeared at Niagara demanding 100 soldiers to aid against the

invaders. The hard-pressed British commander refused, and Brodhead’s destructive expedition went largely unopposed.

Kayahsota├ was sent from Niagara in 1780 on a familiar diplomatic task. Anxious to keep the alliance of the western Indians,

Guy Johnson dispatched him on a tour of the Ohio country to call a conference at Detroit. Most of the chiefs of the region

were absent carrying the war into Kentucky with Henry Bird’s expedition; so the messages were left with the Wyandots

for delivery later in the summer. There is some evidence that Kayahsota├ then commanded a party of 30 Wyandots who raided

near Fort McIntosh (Rochester, Pa) in July. In the spring of 1781 Kayahsota├ was again on the diplomatic trail, but illness

detained him for some time at Cattaraugus (near the mouth of Cattaraugus Creek, N.Y.). The ageing chief went to war once more,

leading the party which on 13 July 1782 burned Hannastown, Pa, and then went on to attack Wheeling (W. Va). For all intents

and purposes, the American revolution was over, and the Senecas soon made their peace with the United States. There is one

report that the new republic tried to use Kayahsota├ as a peacemaker in the Ohio region, but for the most part the role devolved

on Kaiũtwah├kũ (Cornplanter), probably a nephew of Kayahsota├. The Ohio Tribe, however, was bent on a major confrontation

with the Americans which Seneca diplomacy was powerless to stop. As events moved towards a climax, Kayahsota├ carried personal

and public messages to the American commander, Anthony Wayne, at Pittsburgh in 1792, and accompanied Cornplanter to a meeting

with Wayne in 1793. Wayne was organizing and training his force so that he could invade the Ohio country and subdue its native

inhabitants, and he was to achieve success at the battle of Fallen Timbers (near Waterville, Ohio) in August 1794. Cornplanter’s

diplomatic efforts earned him a grant of land in Pennsylvania, and he and his Seneca followers gathered on it at the close

of the century. There Kayahsota├ died and was buried, probably in 1794. From: historical accounts & records

The fortunes of war turned against the French and their native allies, and despite the assistance given by Kayahsota├ and

other western Senecas, in 1758 Fort Duquesne fell to the British under John Forbes. The French effectively withdrew from the

west in 1759, but hostilities were not at an end. The miserly attitude adopted by Amherst with respect to Native American

presents aggravated the difficulties between the native population and the British, and the result was the outbreak generally

known as the Pontiac rebellion, although it has been called the Kiyasuta and Pontiac war. Political leaders in the egalitarian

societies found in most of North America prior to its conquest by the white man lacked the authority to compel their constituents

to action and relied instead upon suasion. As he had no power to dictate public policy, and only his personal diplomatic skills

to shape public opinion, Kayahsota├ would not seem to merit a major share of the blame, or praise, for the conflict which

flared on the western frontier in 1763. The native population was nearly unanimous with respect to the desirability of attacking

the red-coated troops who had so recently replaced the French in that region, but Kayahsota├ was influential in focusing resentment

and was among the first to urge the use of force. As early as 1761 he and his fellow Seneca Tahahaiadoris were circulating

a large red wampum belt, known as the war hatchet, among the native population clustered about Detroit. According to Sir William

Johnson’s deputy, George Croghan, they privately admitted to him that the purpose was to bring on a general uprising

from Detroit to the Mohawk valley. Sir William himself came to Detroit in September 1761 to counteract their efforts. At the

conference Kayahsota├ denied the charges made against him but found himself contradicted by a Wyandot, and the resulting uproar

was calmed only by the efforts of Johnson. Later an Ottawa speaker, MÚcatÚpilÚsis, publicly identified Kayahsota├ as “the

bad Bird lately Amongst us.” Johnson met with Kayahsota├ privately and tried to convince the Seneca leader of the error

of his ways, but his diplomacy obtained only a brief respite. In June 1763 the frontier erupted in a general war. Most of

the Six Nations, including the eastern Senecas, remained at peace, but the western Senecas were active against the British.

Kayahsota├ and a few other Senecas fought alongside the Delawares in the siege of Fort Pitt (formerly Fort Duquesne) and against

the relief force under Colonel Henry Bouquet. Native testimony also suggests that he took part in the capture of the British

post at Venango (Franklin, Pa). After the fighting had run its course, Kayahsota├ was among those who signed a preliminary

peace agreement on 12 Aug. 1764, and he was given the task of carrying the conditions of peace to those groups still at war.

At the end of October 1764 Kayahsota├ came to Tuscarawas (near Bolivar, Ohio) with delegates of the Delawares, Shawnees, and

Senecas to meet with Bouquet. Bouquet’s major concern by this time was the release of white captives still in Native

American hands. He reported the negotiations a success, despite the necessity of dispatching Kayahsota├ to the Delawares to

protest the murder of a British soldier. Over 200 white captives were released (although some proved so reluctant to rejoin

white society that Bouquet had to post guards to prevent them from returning to their native captors). Following the conference,

Bouquet sent Kayahsota├ to fetch white captives held by the Wyandots. In the spring of 1765 George Croghan met with the western

Indians at Fort Pitt, and the return of prisoners was again a central issue. Kayahsota├ was there and was appointed a delegate

to yet another conference, this time with Sir William Johnson at Johnson Hall (Johnstown, NY). Kayahsota├ and other western

Indians met there from 4 to 13 July to negotiate a final peace. On the last day Kayahsota├ affixed the sign of a wolf, the

eponym of his clan, to the treaty. In the following decade Kayahsota├ served continually as an intermediary between the British

authorities and the native inhabitants of the Ohio region. Frequently journeying between Johnson Hall and the Ohio, he carried

wampum belts and Johnson’s words in attempts to preserve peace in the west or to isolate diplomatically such uncooperative

groups as the Shawnees. The Native American superintendent considered him a “Chief of much Capacity and vast Influence”

and found him “very useful on such Occasions.” When a group of Shawnees appeared at Fort Pitt in the spring of

1773 with a complaint about Virginia surveyors, it was Kayahsota├ who received them and presented them with a wampum belt.

On the other hand the western Native Americans often conveyed their grievances to Johnson through him. For example, the participants

in a major conference held at Fort Pitt in October 1773 sent Kayahsota├ to Johnson Hall with their complaints about unregulated

trade, particularly in liquor. Kayahsota├ was never able to carry out one of Johnson’s major aims, the removal of the

Mingos, Iroquois emigrants to the Ohio country, back to their old homes in what is now upstate New York. The superintendent

feared that these warriors, far from the moderating influence of the Onondaga council and even farther from Johnson Hall,

and carrying with them the well-earned reputation that the Iroquois enjoyed as fighting men, might join their Algonkian speaking

neighbors against the British. Johnson had first asked Kayahsota├ to persuade the Mingos to return in 1765, and the Seneca

chief was still trying unsuccessfully to carry out the policy in 1773. In addition to all his diplomatic activity, Kayahsota├

found time to work for various whites in the Ohio valley. His knowledge of the geography and the inhabitants of the region

enabled him to serve as guide and intermediary for travellers and traders. His duties took him several times to Fort de Chartres

(near Prairie du Rocher) in the Illinois country. When the American revolution broke out, Kayahsota├ had already established

a close working relationship with Guy Johnson, successor to Sir William as Native American superintendent. The rebels, however,

were active in courting the chief’s favor. Kayahsota├ was among the Indian leaders meeting representatives of the Continental

Congress at Fort Pitt in October 1775. He agreed that the Shawnees should surrender prisoners and booty captured in their

war with Virginia, which had just concluded, and consented to go to their towns to make sure the surrender was carried out.

In return, he asked for assurance that the boundary of white settlement established by the treaty of Fort Stanwix (1768) would

be honoured. He also observed astutely that disputes among the rebel representatives might well inhibit the kindling of a

bright council fire so necessary for effective Indian-white communication. The Six Nations held a neutral stance during the

early years of the American revolution. Kayahsota├ moved freely between the rebel post at Fort Pitt and the loyalist stronghold

at Niagara (near Youngstown, N.Y.). To the commandants at both forts he proclaimed the determination of the Six Nations to

take no part in any war between Britain and the colonies. At Fort Pitt on 6 July 1776 he emphasized native opposition to the

movement through Indian lands by armies of either side. Later, he went on an embassy to the Mingos to bring them into line

with the neutral position assumed by the other western tribes. In recognition of his services, the Continental Congress awarded

him a colonel’s commission and a silver gorget. It was inevitable, however, that the native population would eventually

enter the contest on the side of the crown. There were too many grievances against the encroaching Americans and, although

the war disrupted normal economic life, an active role in the conflict promised ample material rewards. With the decision

of the Six Nations in the summer of 1777 to abandon neutrality, Kayahsota├ began to work actively for the royal, and Indian,

cause. Later in the summer he was one of a large body of Indians who accompanied Barrimore Matthew St Leger against the rebels

at Fort Stanwix (Rome, N.Y.). The siege of this fort at the western end of the Mohawk valley was in its initial phase when

word came from Mary Brant [Ko˝watsi├tsiaiÚ˝ni] that 800 militiamen were marching to attack the besiegers. It was primarily

the Indians who were dispatched to meet them, and the rebels were repulsed in the bloody battle of Oriskany nearby. Kayahsota├

was in the field again soon; in December 1777 Simon Girty* reported that the Seneca chief or members of his war party had

killed four people near Ligonier, Pa. When in 1779 a rebel army commanded by Daniel Brodhead marched from Fort Pitt up the

Allegheny river valley, burning Seneca villages, Kayahsota├ appeared at Niagara demanding 100 soldiers to aid against the

invaders. The hard-pressed British commander refused, and Brodhead’s destructive expedition went largely unopposed.

Kayahsota├ was sent from Niagara in 1780 on a familiar diplomatic task. Anxious to keep the alliance of the western Indians,

Guy Johnson dispatched him on a tour of the Ohio country to call a conference at Detroit. Most of the chiefs of the region

were absent carrying the war into Kentucky with Henry Bird’s expedition; so the messages were left with the Wyandots

for delivery later in the summer. There is some evidence that Kayahsota├ then commanded a party of 30 Wyandots who raided

near Fort McIntosh (Rochester, Pa) in July. In the spring of 1781 Kayahsota├ was again on the diplomatic trail, but illness

detained him for some time at Cattaraugus (near the mouth of Cattaraugus Creek, N.Y.). The ageing chief went to war once more,

leading the party which on 13 July 1782 burned Hannastown, Pa, and then went on to attack Wheeling (W. Va). For all intents

and purposes, the American revolution was over, and the Senecas soon made their peace with the United States. There is one

report that the new republic tried to use Kayahsota├ as a peacemaker in the Ohio region, but for the most part the role devolved

on Kaiũtwah├kũ (Cornplanter), probably a nephew of Kayahsota├. The Ohio Tribe, however, was bent on a major confrontation

with the Americans which Seneca diplomacy was powerless to stop. As events moved towards a climax, Kayahsota├ carried personal

and public messages to the American commander, Anthony Wayne, at Pittsburgh in 1792, and accompanied Cornplanter to a meeting

with Wayne in 1793. Wayne was organizing and training his force so that he could invade the Ohio country and subdue its native

inhabitants, and he was to achieve success at the battle of Fallen Timbers (near Waterville, Ohio) in August 1794. Cornplanter’s

diplomatic efforts earned him a grant of land in Pennsylvania, and he and his Seneca followers gathered on it at the close

of the century. There Kayahsota├ died and was buried, probably in 1794. From: historical accounts & records

|