|

Warriors Citation

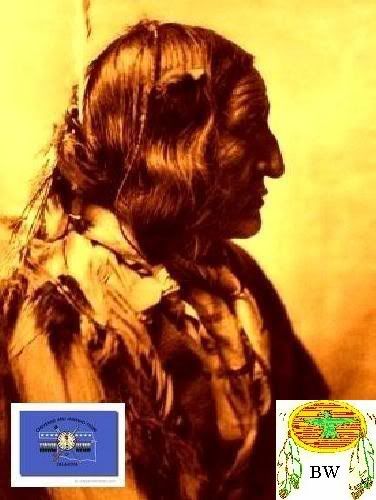

Chief Little Wolf

(1818 – 1904)

Little Wolf was a principal chief of the Northern Cheyennes during early contact with Anglo-American traders, settlers and

troops. With Dull Knife, Little Wolf led the Cheyennes from exile in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) back to their homeland

in present-day eastern Montana during the late 1870s. This diaspora, completed in direct contradiction to orders by the U.S.

Army, is chronicled in Mari Sandoz's 'Cheyenne Automn (1953)'. Little Wolf was the bearer of the Sacred Chief's Bundle of

the Northern Cheyennes and therefore carried the highest personal responsibility for the preservation of the people.

Little Wolf was reputed to have been a notable warrior as early as the middle 1830s, probably his late teenage years. In 1851,

along with other Cheyennes, Little Wolf ceased warfare against encroaching whites in exchange for an Indian agency and annuities.

The agency was not established, and annuity payments arrived only rarely, but Little Wolf counseled peace with the European

Americans, with one exception. In 1865, he took part in an attack on U.S. Army troops to avenge the unprovoked murder of Black

Kettle's band of Cheyenes at the Sand Creek massacre in 1864.

In 1876, in his late fifties. Little Wolf could still outrun all of the younger Cheyenne warriors. He had two sons, who were

called Pawnee and Woodenthigh by whites. He also had a daughter, Pretty Walker, and two wives, Quite One and Feather on Head.

Little Wolf's Cheyennes did not take part in the battle against George Armstrong Custer's troops at the Little Bighorn on

June 25, 1876, but were caught up in waves of U.S. Army retribution afterward. Little Wolf's people came to the aid of Dull

Knife's Cheyennes as their village on the Powder River was destroyed by the U.S. Army. Little Wolf was shot seven times but

survived.

Little Wolf and Dull Knife's bands escaped into the Yellowstone country during the winter of 1876-1877 but surrendered because

they were hungry and because General Nelson Miles and General George Crook both promised them a reservation in their homeland

and an Indian agent to conduct business with the federal government, including delivery of annuities. After the surrender,

all of the general's promises were broken. Little Wolf had even enlisted as a scout for Crook when he was told that his people

would get no more food unless they accepted the army's orders to move to Indian Territory. The Cheyennes departed only when

they realized that the alternative was starvation, because the buffalo had become too scarce to hunt.

In the middle of August 1878, Dull Knife and Little Wolf pleaded with Indian agent John A. Miles to let them return home.

Half the band had died, mostly of disease, during a year in Oklahoma. Dull knife himself was shaking with fever as they talked.

Miles asked for a year to work on the problem, and Little Wolf told him the Cheyennes would be dead in a year. Three weeks

later, ten young Cheyennes left the reservation in the night, and Agent Miles demanded that Little Wolf give up ten hostages

until troops could locate the runaways. After Little Wolf refused, Miles said that rations would be withheld. Little Wolf

became angry and told Miles that his people were already starving. "Last night I saw children eating grass because they had

no food. Will you take the grass from them ?" Little Wolf asked.

The Cheyennes then left Oklahoma on their own with army troops in persuit. They evaded recapture as they fought off the troops

in several rear guard actions during the fall, but they suffered many casualties. The complex sequence of battles and the

Cheyennes suffering is described in detail in Sandoz's book. Near present-day White Clay Creek, Nebraska, the Cheyennes split

into two groups. Dull Knife and 150 others went into Red Cloud Agency to surrender. Little Wolf and a roughly equal number

headed into the Nebraska Sand Hills, where they spent the winter in hiding.

The next March, Little Wolf's band moved out of the Sand Hills to the mouth of the Powder River, where they encountered Lieutnant

W. P. Clark and an army unit of Cheyenne and Lakota scouts. Clark persuaded Little Wolf and his followers to surrender to

General Miles (whom Little Wolf knew as "Bear Coat") at Fort Keough. This time, the survivors of Little Wolf's band were allowed

to remain near their homeland on the Northern Plains.

During the first reservation winter, 1879-1880, Little Wolf, who had been drinking, shot and killed the Cheyenne Thin Elk,

who had been an sntsgonist of Little Wolf since he had made advances on Little Wolf's wives almost a half century earlier.

Thin Elk's relatives then ransacked Little Wolf's lodge, which was held as a traditional Cheyenne right of a family aggrieved

by murder. Little Wolf's role as a leader of his people ended with that murder. After a quarter century of reservation life,

Little Wolf died in 1904.

From: historical accounts & records

LINK TO BRAVEHORSE WARRIORS VOLUME TWO

|