|

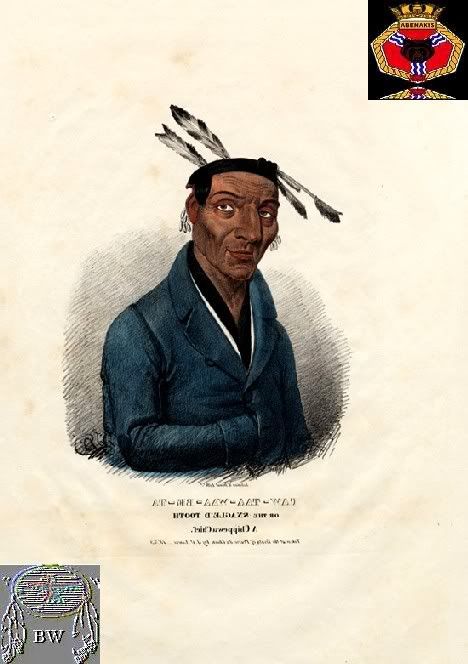

BRAVEHORSE WARRIOR Sauguaaram

Penobscot Abenaki Warrior

Chief Sauguaaram

Warrior Citation

SAUGUAARAM (Laron, Loring, Loron, Sagouarrab, Sagouarrat, Saguaarum, Seguaron), Penobscot Abenaki sachem, warrior, orator;

fl. 1724–51 in the vicinity of the Penobscot River, Massachusetts (now Maine): Sauguaaram first appears in historical

records during Dummer’s War (1722–27) between the Abenakis and Massachusetts. After the deaths of Mog and Father

Sébastien Rale at Norridgewock (Narantsouak; now Old Point, Madison, Me.) in 1724 and the second destruction of their own

village early in 1725, the Penobscots considered the war lost and accepted Massachusetts’ invitation to negotiate a

treaty. Although Wenemouet was Sauguaaram’s superior in rank, it was Sauguaaram who spoke for the tribe at the conferences

in July and August 1725, November and December 1725, and again in July and August 1726.

Chief Sauguaaram

Warrior Citation

SAUGUAARAM (Laron, Loring, Loron, Sagouarrab, Sagouarrat, Saguaarum, Seguaron), Penobscot Abenaki sachem, warrior, orator;

fl. 1724–51 in the vicinity of the Penobscot River, Massachusetts (now Maine): Sauguaaram first appears in historical

records during Dummer’s War (1722–27) between the Abenakis and Massachusetts. After the deaths of Mog and Father

Sébastien Rale at Norridgewock (Narantsouak; now Old Point, Madison, Me.) in 1724 and the second destruction of their own

village early in 1725, the Penobscots considered the war lost and accepted Massachusetts’ invitation to negotiate a

treaty. Although Wenemouet was Sauguaaram’s superior in rank, it was Sauguaaram who spoke for the tribe at the conferences

in July and August 1725, November and December 1725, and again in July and August 1726.

The Penobscots’ moves for peace were a radical break with the policy of the French and the Canadian Abenakis. To maintain

the traditional alliance, Sauguaaram travelled to Canada between conferences, trying unsuccessfully to persuade them to agree

to a peace. In the negotiations with the English, Sauguaaram achieved an implicit acceptance by Massachusetts of the presence

of Jesuit missionaries among his tribe and by helping improve trade relations between the Penobscots and the English he laid

the cornerstone for the subsequent peace. Despite his pleading, however, Massachusetts refused to admit that her settlements

had caused the war, nor would she agree to limit them. She also insisted that the ratifying tribes aid her in suppressing

future Native American uprisings, and this article became a strong irritant throughout the remaining colonial wars. War weariness,

not generous concessions, led Sauguaaram and the Penobscots to accept a tentative agreement. Sauguaaram repudiated the agreement

in January 1726 [n.s.], after Étienne Lauverjat, the missionary at Pannawambskek (Panaouamské; Indian Island, Old Town, Me.),

interpreted the document to him. He had not intended, the sachem said, to acknowledge the British king or to agree to force

the other tribes to submit. Whether there had been a genuine misunderstanding, or whether Sauguaaram’s move was a tactic

of negotiation, Massachusetts was unwilling to make further concessions. So Sauguaaram acquiesced, and the Penobscots accepted

the treaty on 5 Aug. 1726. Sauguaaram learned a valuable lesson from the treaty negotiations: Massachusetts would not compromise

her claims, and the French were hostile to conferences in any case. His solution was to maintain good relations with both

colonies. Pleased by his cooperation, Lieutenant Governor William Dummer of Massachusetts called him a “particular Friend”

and sent him a gun marked with his totem. Sauguaaram was unusually favoured by the truck master at Fort St George (now Thomaston,

ME) in return for information. When the treaty that Massachusetts had negotiated with the Penobscots was ratified by all the

Abenaki tribes in July 1727, Sauguaaram signed it. He wrote to Governor Charles de Beauharnois, however, reaffirming his original

interpretation of the document. “If, then, anyone should produce any writing that makes me speak otherwise, pay no attention

to it,” he explained, “for I know not what I am made to say in another language. . . .” Although eager to

keep on good terms with both colonies, Sauguaaram remembered the Penobscots’ interests. When Father René-Charles de

Breslay was mistreated in Nova Scotia, Sauguaaram angrily reminded the Massachusetts governor that “as to our Religion,

Wee were not to Interrup’t one the other in the Injoyment of itt.” On the same grounds he refused an offer of

Protestant missionaries in 1732, and led his tribe’s opposition to English settlements in the Penobscot River region.

The dispute over the settlements drove the Penobscots into closer ties with the French, and several sachems surrendered their

English commissions to Governor Beauharnois. Sauguaaram himself had never accepted one of these tokens of English favour,

and he complained in fact to the Massachusetts governor that they made the Native Americans “exceedingly proud, & they

breed mutinies & won’t come to Prayers, but do nothing but get drunk.” The Penobscots were still determined to

preserve good relations with both English and French, and in accordance with the treaty Sauguaaram spent the summer of 1740

calming the Abenakis of Saint-François, who were angered by Massachusetts’ expansion. On his return he exasperated Governor

Jonathan Belcher by cautioning Massachusetts to avoid irritating the other Abenaki tribes. “It looks as if you were

ready,” Belcher told him, “to take up the Hatchet and were directed in it by the French. . . .” “We

are a free People,” Sauguaaram replied. Sauguaaram always led the attempt to achieve better trading conditions. He

complained to the Massachusetts governor about prices and about the acting truck master at Fort St George. He also frequently

asked that the rum trade be more closely regulated because “it interrupts our Prayers & does us Mischeif. . . .”

By the fall of 1744 the Indians of Nova Scotia and the Saint John River had begun open warfare against the English. Governor

William Shirley of Massachusetts had hoped to prevent the Abenakis from joining the French, but some of the Penobscots, provoked

in part by his demand that they join in suppressing the outbreak and attacked Fort St George in June 1745. Sauguaaram attempted

to soothe the English in October, when he and three other Native Americans brought word that “the Jesuits have told

them [the Native Americans] not to hurt the English any more. . . .” That night Sauguaaram and his companions were attacked

by a scouting party, and only Sauguaaram escaped. He and the remaining Penobscots fled to Canada, where he told Beauharnois

that 25 warriors had set out to take revenge on Massachusetts. The Penobscots remained in Canada, sending forays into New

England, for the rest of the war. One of Sauguaaram’s sons was killed in the conflict, and the sachem was reluctant

to make peace. Although he foresaw that “when there is a French war we must break again,” the Penobscots finally

ended their part in King George’s War with a treaty signed at Falmouth (Portland, Me.) in October 1749. The treaty failed

almost immediately when a Norridgewock Native American was killed at Wiscasset, Massachusetts (now Maine), in December 1749.

You promised us justice, Sauguaaram reminded the lieutenant governor, “so we expect you will realy do it.” By

June 1750, however, one of the accused Englishmen had been acquitted and the trial of the other two had been postponed. Although

the French encouraged the Abenakis to take revenge, Sauguaaram and the Penobscots assured Massachusetts that they desired

peace. The final reference to Sauguaaram in Massachusetts documents reveals that in September 1751 he was still working for

peace, but all his efforts and those of the Norridgewock sachem Nodogawerrimet failed to prevent continued English intrusion

into Native American lands. Sauguaaram’s life reflects all the major issues between the Abenakis and Massachusetts.

Under his leadership the Penobscots protected their religion, agitated for better trading conditions, opposed new settlements,

and balanced their affairs between the demands of New France and New England. From: historical accounts & records

The Penobscots’ moves for peace were a radical break with the policy of the French and the Canadian Abenakis. To maintain

the traditional alliance, Sauguaaram travelled to Canada between conferences, trying unsuccessfully to persuade them to agree

to a peace. In the negotiations with the English, Sauguaaram achieved an implicit acceptance by Massachusetts of the presence

of Jesuit missionaries among his tribe and by helping improve trade relations between the Penobscots and the English he laid

the cornerstone for the subsequent peace. Despite his pleading, however, Massachusetts refused to admit that her settlements

had caused the war, nor would she agree to limit them. She also insisted that the ratifying tribes aid her in suppressing

future Native American uprisings, and this article became a strong irritant throughout the remaining colonial wars. War weariness,

not generous concessions, led Sauguaaram and the Penobscots to accept a tentative agreement. Sauguaaram repudiated the agreement

in January 1726 [n.s.], after Étienne Lauverjat, the missionary at Pannawambskek (Panaouamské; Indian Island, Old Town, Me.),

interpreted the document to him. He had not intended, the sachem said, to acknowledge the British king or to agree to force

the other tribes to submit. Whether there had been a genuine misunderstanding, or whether Sauguaaram’s move was a tactic

of negotiation, Massachusetts was unwilling to make further concessions. So Sauguaaram acquiesced, and the Penobscots accepted

the treaty on 5 Aug. 1726. Sauguaaram learned a valuable lesson from the treaty negotiations: Massachusetts would not compromise

her claims, and the French were hostile to conferences in any case. His solution was to maintain good relations with both

colonies. Pleased by his cooperation, Lieutenant Governor William Dummer of Massachusetts called him a “particular Friend”

and sent him a gun marked with his totem. Sauguaaram was unusually favoured by the truck master at Fort St George (now Thomaston,

ME) in return for information. When the treaty that Massachusetts had negotiated with the Penobscots was ratified by all the

Abenaki tribes in July 1727, Sauguaaram signed it. He wrote to Governor Charles de Beauharnois, however, reaffirming his original

interpretation of the document. “If, then, anyone should produce any writing that makes me speak otherwise, pay no attention

to it,” he explained, “for I know not what I am made to say in another language. . . .” Although eager to

keep on good terms with both colonies, Sauguaaram remembered the Penobscots’ interests. When Father René-Charles de

Breslay was mistreated in Nova Scotia, Sauguaaram angrily reminded the Massachusetts governor that “as to our Religion,

Wee were not to Interrup’t one the other in the Injoyment of itt.” On the same grounds he refused an offer of

Protestant missionaries in 1732, and led his tribe’s opposition to English settlements in the Penobscot River region.

The dispute over the settlements drove the Penobscots into closer ties with the French, and several sachems surrendered their

English commissions to Governor Beauharnois. Sauguaaram himself had never accepted one of these tokens of English favour,

and he complained in fact to the Massachusetts governor that they made the Native Americans “exceedingly proud, & they

breed mutinies & won’t come to Prayers, but do nothing but get drunk.” The Penobscots were still determined to

preserve good relations with both English and French, and in accordance with the treaty Sauguaaram spent the summer of 1740

calming the Abenakis of Saint-François, who were angered by Massachusetts’ expansion. On his return he exasperated Governor

Jonathan Belcher by cautioning Massachusetts to avoid irritating the other Abenaki tribes. “It looks as if you were

ready,” Belcher told him, “to take up the Hatchet and were directed in it by the French. . . .” “We

are a free People,” Sauguaaram replied. Sauguaaram always led the attempt to achieve better trading conditions. He

complained to the Massachusetts governor about prices and about the acting truck master at Fort St George. He also frequently

asked that the rum trade be more closely regulated because “it interrupts our Prayers & does us Mischeif. . . .”

By the fall of 1744 the Indians of Nova Scotia and the Saint John River had begun open warfare against the English. Governor

William Shirley of Massachusetts had hoped to prevent the Abenakis from joining the French, but some of the Penobscots, provoked

in part by his demand that they join in suppressing the outbreak and attacked Fort St George in June 1745. Sauguaaram attempted

to soothe the English in October, when he and three other Native Americans brought word that “the Jesuits have told

them [the Native Americans] not to hurt the English any more. . . .” That night Sauguaaram and his companions were attacked

by a scouting party, and only Sauguaaram escaped. He and the remaining Penobscots fled to Canada, where he told Beauharnois

that 25 warriors had set out to take revenge on Massachusetts. The Penobscots remained in Canada, sending forays into New

England, for the rest of the war. One of Sauguaaram’s sons was killed in the conflict, and the sachem was reluctant

to make peace. Although he foresaw that “when there is a French war we must break again,” the Penobscots finally

ended their part in King George’s War with a treaty signed at Falmouth (Portland, Me.) in October 1749. The treaty failed

almost immediately when a Norridgewock Native American was killed at Wiscasset, Massachusetts (now Maine), in December 1749.

You promised us justice, Sauguaaram reminded the lieutenant governor, “so we expect you will realy do it.” By

June 1750, however, one of the accused Englishmen had been acquitted and the trial of the other two had been postponed. Although

the French encouraged the Abenakis to take revenge, Sauguaaram and the Penobscots assured Massachusetts that they desired

peace. The final reference to Sauguaaram in Massachusetts documents reveals that in September 1751 he was still working for

peace, but all his efforts and those of the Norridgewock sachem Nodogawerrimet failed to prevent continued English intrusion

into Native American lands. Sauguaaram’s life reflects all the major issues between the Abenakis and Massachusetts.

Under his leadership the Penobscots protected their religion, agitated for better trading conditions, opposed new settlements,

and balanced their affairs between the demands of New France and New England. From: historical accounts & records

|