|

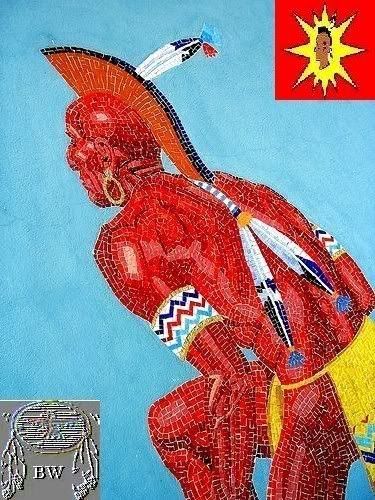

BRAVEHORSE WARRIOR Deserontyon

Mohawk Warrior

Chief Deserontyon

Warrior Citation

DESERONTYON (Odeserundiye), JOHN (Captain John), Mohawk chief; b. in the 1740s, probably in the Mohawk valley of New York;

d. 7 Jan. 1811 at the Mohawk settlement on the Bay of Quinte, Upper Canada.

As a young boy John Deserontyon accompanied Sir William Johnson to Niagara (near Youngstown, N.Y.) when the British

laid siege to that fort in 1759, and he was with the forces under Major-General Jeffery Amherst that descended the St Lawrence

to attack Montreal (Que.) the following year. In the spring and early summer of 1764, during the disturbances associated with

Pontiac’s uprising, he was one of several protecting guarding whites from Seneca attacks, probably in the Niagara region.

In mid summer he joined the forces led by Colonel John Bradstreet which were sent to Detroit (Mich.) to help impose peace

on the Delawares and Shawnees. Like other Mohawks, Deserontyon was bitter about Bradstreet’s conduct of the expedition,

recalling that “he only made a great loss to the King. There was a vessel wrecked, and a great number of his people

died with hunger, & we the Mohawks scarcely returned to Niagara.” At some time prior to the American revolution Deserontyon

became a chief in the village at Fort Hunter (N.Y.). When the war erupted, the native people were courted by both the British

and the Americans. Deserontyon openly sided with Britain and the interests of the Johnson family, as the majority of Mohawks

ultimately did. Early in the summer of 1775 he was with a party that escorted Guy Johnson and Christian Daniel Claus to Montreal.

The decision to leave their families at this dangerous time in order to aid Johnson and Claus was not easy for the Mohawks

but, Deserontyon later wrote, “we thought that it would be very hard if we should lose them for it was only them helped

us.” He subsequently returned to the Mohawk valley and that fall Sir John Johnson, who was still resident there, sent

him to Montreal with a letter. Deserontyon arrived at Fort St Johns (Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu) while it was under siege by

the Americans and barely escaped when the British decided to surrender to Richard Montgomery’s forces. Reaching Montreal

early in November he “found the people that were on the King’s side all troubled – did not know what to

do” and that Governor Guy Carleton “did neither know what would be done for the people, for the Americans were

already at La Prairie.” In May 1776 Sir John, having learned that an expedition was about to be dispatched from Albany

to seize him and his property, sent Deserontyon to ascertain the date of the troop’s departure. This object the chief

accomplished, slipping past the American guards in the darkness and thus helping Johnson make his escape to Montreal. In the

autumn Deserontyon and many Fort Hunter Mohawks also fled north.

Chief Deserontyon

Warrior Citation

DESERONTYON (Odeserundiye), JOHN (Captain John), Mohawk chief; b. in the 1740s, probably in the Mohawk valley of New York;

d. 7 Jan. 1811 at the Mohawk settlement on the Bay of Quinte, Upper Canada.

As a young boy John Deserontyon accompanied Sir William Johnson to Niagara (near Youngstown, N.Y.) when the British

laid siege to that fort in 1759, and he was with the forces under Major-General Jeffery Amherst that descended the St Lawrence

to attack Montreal (Que.) the following year. In the spring and early summer of 1764, during the disturbances associated with

Pontiac’s uprising, he was one of several protecting guarding whites from Seneca attacks, probably in the Niagara region.

In mid summer he joined the forces led by Colonel John Bradstreet which were sent to Detroit (Mich.) to help impose peace

on the Delawares and Shawnees. Like other Mohawks, Deserontyon was bitter about Bradstreet’s conduct of the expedition,

recalling that “he only made a great loss to the King. There was a vessel wrecked, and a great number of his people

died with hunger, & we the Mohawks scarcely returned to Niagara.” At some time prior to the American revolution Deserontyon

became a chief in the village at Fort Hunter (N.Y.). When the war erupted, the native people were courted by both the British

and the Americans. Deserontyon openly sided with Britain and the interests of the Johnson family, as the majority of Mohawks

ultimately did. Early in the summer of 1775 he was with a party that escorted Guy Johnson and Christian Daniel Claus to Montreal.

The decision to leave their families at this dangerous time in order to aid Johnson and Claus was not easy for the Mohawks

but, Deserontyon later wrote, “we thought that it would be very hard if we should lose them for it was only them helped

us.” He subsequently returned to the Mohawk valley and that fall Sir John Johnson, who was still resident there, sent

him to Montreal with a letter. Deserontyon arrived at Fort St Johns (Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu) while it was under siege by

the Americans and barely escaped when the British decided to surrender to Richard Montgomery’s forces. Reaching Montreal

early in November he “found the people that were on the King’s side all troubled – did not know what to

do” and that Governor Guy Carleton “did neither know what would be done for the people, for the Americans were

already at La Prairie.” In May 1776 Sir John, having learned that an expedition was about to be dispatched from Albany

to seize him and his property, sent Deserontyon to ascertain the date of the troop’s departure. This object the chief

accomplished, slipping past the American guards in the darkness and thus helping Johnson make his escape to Montreal. In the

autumn Deserontyon and many Fort Hunter Mohawks also fled north.

Throughout the conflict Deserontyon was actively engaged in raids into northern New York by way of Oswego (N.Y.) or the Richelieu

valley, raids which were an indispensable source of intelligence to the British. Following a council with Major John Butler,

apparently in the spring of 1777, he went to Quebec, where he met Major-General John Burgoyn, just arrived from England with

orders to invade New York. The main thrust of Burgoyne’s attack was to be the Richelieu valley, but a secondary advance

under Barrimore Matthew St Leger was to be made down the Mohawk valley; it was in the latter aspect of the campaign that Deserontyon

participated. Early in July he was a leader of a party that spied out the defences of Fort Stanwix (Rome, N.Y.), which St

Leger was planning to attack. The party discovered that the fort was much stronger than had been thought, but the over-confident

commander proceeded without the necessary artillery or reinforcements. While the siege was going on, a force composed largely

of Indians defeated a body of American militia approaching to relieve the fort. Deserontyon fought in this battle of Oriskany,

as did Joseph Brant [Thayendanegea] and Kaie˝├kwaahto˝, and he likely returned to Oswego with Brant after the siege was abandoned

in August [see Benedict Arnold]. In September he was with some Indians who set out from there to join Burgoyne’s forces

south of Lake George, N.Y. As the group passed Fort Stanwix it encountered scouts from the fort and Deserontyon was seriously

wounded. He had recovered sufficiently by 1779, however, to lead at least two scouting parties up the Richelieu valley, and

each time he brought back several prisoners to be interrogated by the British. In the autumn he left Lachine, Que., where

most of the Fort Hunter Mohawks had settled, to take part in Sir John Johnson’s expedition, which was heading west to

retaliate for the recent American devastation of Six Nations country. A year later he was reported to have led a raid from

Montreal to the area south of Saratoga (Schuylerville, N.Y.) and on 13 May 1781 he wrote to Daniel Claus, then deputy agent

for the Six Nations in Canada, informing him that he and his party had returned safely to Carleton Island (N.Y.) from Canajoharie

(near Little Falls). “I propose going to Niagara about some public Business and shall be back in a few days,”

he added. Claus entrusted him with the responsibility of going to the Iroquois settlement at Caughnawaga, Que., in January

1782 to investigate the reported presence of a spy, a report Deserontyon’s acquaintances there denied. The spring and

summer saw Deserontyon leading more forays into the Mohawk valley, destroying mills and cattle and taking prisoners. In spite

of pledges offered at the outset of hostilities and reiterated as late as 1780 by Guy Johnson, then superintendent of the

Six Nations, many of the Iroquois feared that their property and rights in New York would be lost once peace returned, and

indeed the preliminary articles signed on 30 Nov. 1782 made no provision for Indian interests. In the spring, following the

institution of a cease-fire, Deserontyon accompanied Brant and other embittered Six Nations spokesmen to a meeting in Montreal

with Governor Haldimand. Understandably Haldimand tried to reassure the deputation that his government would not abandon them.

In the event of their not being permitted to reoccupy ancestral lands in New York the governor, though he had no official

authority for so doing, eagerly discussed with Brant and Deserontyon the expediency of settling the Indians “on the

north side of Lake Ontario.” Although this arrangement was far from being a satisfactory alternative, the deputies returned

to Fort Niagara and tried to convince their comrades of Britain’s good intentions. The Six Nations’ concern about

the future was reflected, however, in the arrangements they made in August and September with tribes to the west – Delawares,

Shawnees, Cherokees, Creeks, Ojibwas, Ottawas, and Mingos – to oppose American expansion. When in September the definitive

treaty of peace was concluded between Britain and the United States, again no provision was made to restore the Six Nations’

lands in New York. By that time Brant and Deserontyon had seemingly resigned themselves to the situation and had already toured

a site on the Bay of Quinte surveyed for the Six Nations by Samuel Johannes Holland (although Deserontyon claimed years later

that Nova Scotia had first been selected and then discarded as an asylum). Brant had initially seemed satisfied with the choice

of Quinte, but by March 1784 he had decided instead in favour of a region he had visited some years before – the valley

of the Grand River. Political and strategic considerations appeared to govern Brant’s change of mind: the site offered

greater proximity to his allies the western Indians and to his kinsmen the Senecas and Onondagas, who were still clinging

to a vulnerable position on the flanks of American settlement in New York. Brant’s decision, however, did not go down

well with Deserontyon, who much preferred the Bay of Quinte site on the equally strategic grounds that it afforded a haven

far removed from the Americans, a people he likened to “a worm that cuts off the corn as soon as it appears.”

Indeed even before Haldimand arranged the transfer of the Grand River lands to Brant and his people the Fort Hunter Mohawks

had left Lachine for the Bay of Quinte. Though he sympathized with the arguments of both sides, the anxious Haldimand was

put out by this turn of events, for he had maintained all along that “a determined Union and Attachment can alone support

. . . [the Mohawks’] Strength and Consequence. . . .” Sir John Johnson was less polite; he openly ridiculed Deserontyon’s

decision to stick by the Quinte location. So did Brant, who resented his fellow chief’s refusal to follow his lead and

join his Mohawks and other Six Nations families on the banks of the Grand. Deserontyon’s reluctance may have been shaped

as much by tradition as by strategic considerations. The creation of distinctive and autonomous villages within the tribal

framework was not an unusual practice among the Iroquois. For example, the village at Fort Hunter had been a community deliberately

set off from the one at Canajoharie, where Brant often made his headquarters, and this history of a separate existence may

well have inspired the Fort Hunter Mohawks’ decision to organize a settlement of their own at the Bay of Quinte. Anoghsoktea

(Isaac Hill) and Kanonraron (Aaron Hill) elected to join Brant on the Grand, but their stay was short-lived. Within four years,

following lengthy and bitter disputes with the strong-willed Brant, they returned crestfallen and repentant, much to Deserontyon’s

grim satisfaction. Meanwhile Haldimand, though still aiming at uniting the two communities into one settlement, had none the

less assisted Deserontyon. He arranged the purchase from the Mississaugas of a 12 by 13 mile tract fronting on the bay and

transferred it to the Fort Hunter Mohawks. The transaction was made official on 1 April 1793, when after repeated requests

from Deserontyon Lieutenant Governor Simcoe formally authorized the grant of the tract to its residents. Contrary to Deserontyon’s

wishes, however, the right to dispose of the land as they saw fit was not bestowed. Like other Six Nations leaders, Deserontyon

was compensated by Britain for losses suffered during the war. Having left behind in New York 82 acres of cultivated land,

a barn, house and furniture, sleigh, carriage, wagon, and various farm animals, he received a lump sum of $1100, yearly presents,

and an annual pension of $70, together with an assurance that his son Peter John would be properly educated at a boarding-school.

In recognition of his services to the Indian Department he was also given 3,000 acres of land. Deserontyon was active on behalf

of the educational and spiritual welfare of his Mohawks. In response to his entreaties, a teacher named Vincent, who would

also double as a catechist, was appointed to the settlement in 1785 on the understanding that his salary would be paid by

the Indian Department. This move and the visits paid by John Stuart, formerly the Anglican missionary at Fort Hunter, were

received with great joy by Deserontyon and his fellow Indians. Official assistance was also offered to the little community,

which in 1788 numbered about a hundred, with the construction of the necessary schoolhouse and church. The latter edifice,

when finally completed late in 1791 through the exertions of the Mohawks themselves and with the aid of a small grant from

the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, was graced with some of the communion silver that Deserontyon had recovered

in 1783 from the chapel at Fort Hunter. All these developments augured well for the settlement, particularly when Vincent

was recruited to assist Stuart, now the parish clergyman at Cataraqui (Kingston), in the translation into Mohawk of the Gospel

of St Matthew. In 1789, however, with the work apparently unfinished, Vincent was dismissed and his place taken by an Indian

teacher named Peter. Although the latter’s credentials were deemed sound enough, he turned out to be an alcoholic and

had to be let go in turn, a state of affairs that was said to have thrown the community into confusion. In 1791 John Norton

was appointed, but he shortly quit the post on the grounds that the work was too confining and the Indians too demanding.

The problem of providing adequate instruction for Indian youth was not, it would appear, satisfactorily resolved in Deserontyon’s

lifetime. Although the authorities ultimately swallowed their objections to the chief’s decision to stay at the Bay

of Quinte and appreciated his offer of aid in 1794 when another Anglo-American war threatened, his leader-ship was not without

controversy. He annoyed Haldimand and the Indian Department in 1784 by trying to provide for the local Mississaugas when supplies

were distributed to the Mohawks as loyalists. Moreover, the factionalism endemic among the Six Nations also proved a serious

problem at the Bay of Quinte settlement. Following the Hills’ return from the Grand River, disputes reminiscent of those

that had disrupted Brant’s domain broke out. The source of the trouble is not clear. Deserontyon claimed that Isaac

Hill refused to attend council meetings and had set up his own council, and that members of Hill’s faction had opened

public houses, the sign over one being a picture of the devil. Hill alleged that Deserontyon had inflated his expenses for

the trip he made to Albany with Brant in 1797 to obtain compensation for lands the Mohawks had lost. The struggle culminated

in the killing by Hill’s party of two of Deserontyon’s relatives and in the intervention of William Claus, the

acting deputy superintendent general of Indian affairs in Upper Canada. Claus summoned a council in September 1800 to air

and, if possible to resolve the differences between the warring groups. Only after Hill publicly agreed to exclude himself

from the settlement’s affairs did an adamant Deserontyon agree to shake hands and permit the dangerous episode to close.

But Deserontyon’s problems did not end there. The closing years of his life were troubled by the so-called timber war

brought on when white lumbermen encroached on Indian lands. Although the depredations were condemned by both Deserontyon and

John Ferguson, a local Indian Department official, the chief was accused by his enemies of serving as a paid broker for white

timber interests while purportedly acting for the Indians. He strongly denied the charge, but the issue was still unresolved

when he died on 7 Jan. 1811. Like Joseph Brant, Deserontyon had been educated in a school run by whites and was considerably

acculturated to their customs. Nevertheless, he was described by Daniel Claus as “the clearest & best speaker of the

6 Nations according to the old way.” He was also an accomplished warrior and chief. His career illustrates the role

played by the Six Nations as Britain’s allies during the American revolution. It also serves to illuminate the problems

encountered by the Indian loyalists in the new province of Upper Canada. The town of Deseronto is named in his honour. From:

historical accounts & records

Throughout the conflict Deserontyon was actively engaged in raids into northern New York by way of Oswego (N.Y.) or the Richelieu

valley, raids which were an indispensable source of intelligence to the British. Following a council with Major John Butler,

apparently in the spring of 1777, he went to Quebec, where he met Major-General John Burgoyn, just arrived from England with

orders to invade New York. The main thrust of Burgoyne’s attack was to be the Richelieu valley, but a secondary advance

under Barrimore Matthew St Leger was to be made down the Mohawk valley; it was in the latter aspect of the campaign that Deserontyon

participated. Early in July he was a leader of a party that spied out the defences of Fort Stanwix (Rome, N.Y.), which St

Leger was planning to attack. The party discovered that the fort was much stronger than had been thought, but the over-confident

commander proceeded without the necessary artillery or reinforcements. While the siege was going on, a force composed largely

of Indians defeated a body of American militia approaching to relieve the fort. Deserontyon fought in this battle of Oriskany,

as did Joseph Brant [Thayendanegea] and Kaie˝├kwaahto˝, and he likely returned to Oswego with Brant after the siege was abandoned

in August [see Benedict Arnold]. In September he was with some Indians who set out from there to join Burgoyne’s forces

south of Lake George, N.Y. As the group passed Fort Stanwix it encountered scouts from the fort and Deserontyon was seriously

wounded. He had recovered sufficiently by 1779, however, to lead at least two scouting parties up the Richelieu valley, and

each time he brought back several prisoners to be interrogated by the British. In the autumn he left Lachine, Que., where

most of the Fort Hunter Mohawks had settled, to take part in Sir John Johnson’s expedition, which was heading west to

retaliate for the recent American devastation of Six Nations country. A year later he was reported to have led a raid from

Montreal to the area south of Saratoga (Schuylerville, N.Y.) and on 13 May 1781 he wrote to Daniel Claus, then deputy agent

for the Six Nations in Canada, informing him that he and his party had returned safely to Carleton Island (N.Y.) from Canajoharie

(near Little Falls). “I propose going to Niagara about some public Business and shall be back in a few days,”

he added. Claus entrusted him with the responsibility of going to the Iroquois settlement at Caughnawaga, Que., in January

1782 to investigate the reported presence of a spy, a report Deserontyon’s acquaintances there denied. The spring and

summer saw Deserontyon leading more forays into the Mohawk valley, destroying mills and cattle and taking prisoners. In spite

of pledges offered at the outset of hostilities and reiterated as late as 1780 by Guy Johnson, then superintendent of the

Six Nations, many of the Iroquois feared that their property and rights in New York would be lost once peace returned, and

indeed the preliminary articles signed on 30 Nov. 1782 made no provision for Indian interests. In the spring, following the

institution of a cease-fire, Deserontyon accompanied Brant and other embittered Six Nations spokesmen to a meeting in Montreal

with Governor Haldimand. Understandably Haldimand tried to reassure the deputation that his government would not abandon them.

In the event of their not being permitted to reoccupy ancestral lands in New York the governor, though he had no official

authority for so doing, eagerly discussed with Brant and Deserontyon the expediency of settling the Indians “on the

north side of Lake Ontario.” Although this arrangement was far from being a satisfactory alternative, the deputies returned

to Fort Niagara and tried to convince their comrades of Britain’s good intentions. The Six Nations’ concern about

the future was reflected, however, in the arrangements they made in August and September with tribes to the west – Delawares,

Shawnees, Cherokees, Creeks, Ojibwas, Ottawas, and Mingos – to oppose American expansion. When in September the definitive

treaty of peace was concluded between Britain and the United States, again no provision was made to restore the Six Nations’

lands in New York. By that time Brant and Deserontyon had seemingly resigned themselves to the situation and had already toured

a site on the Bay of Quinte surveyed for the Six Nations by Samuel Johannes Holland (although Deserontyon claimed years later

that Nova Scotia had first been selected and then discarded as an asylum). Brant had initially seemed satisfied with the choice

of Quinte, but by March 1784 he had decided instead in favour of a region he had visited some years before – the valley

of the Grand River. Political and strategic considerations appeared to govern Brant’s change of mind: the site offered

greater proximity to his allies the western Indians and to his kinsmen the Senecas and Onondagas, who were still clinging

to a vulnerable position on the flanks of American settlement in New York. Brant’s decision, however, did not go down

well with Deserontyon, who much preferred the Bay of Quinte site on the equally strategic grounds that it afforded a haven

far removed from the Americans, a people he likened to “a worm that cuts off the corn as soon as it appears.”

Indeed even before Haldimand arranged the transfer of the Grand River lands to Brant and his people the Fort Hunter Mohawks

had left Lachine for the Bay of Quinte. Though he sympathized with the arguments of both sides, the anxious Haldimand was

put out by this turn of events, for he had maintained all along that “a determined Union and Attachment can alone support

. . . [the Mohawks’] Strength and Consequence. . . .” Sir John Johnson was less polite; he openly ridiculed Deserontyon’s

decision to stick by the Quinte location. So did Brant, who resented his fellow chief’s refusal to follow his lead and

join his Mohawks and other Six Nations families on the banks of the Grand. Deserontyon’s reluctance may have been shaped

as much by tradition as by strategic considerations. The creation of distinctive and autonomous villages within the tribal

framework was not an unusual practice among the Iroquois. For example, the village at Fort Hunter had been a community deliberately

set off from the one at Canajoharie, where Brant often made his headquarters, and this history of a separate existence may

well have inspired the Fort Hunter Mohawks’ decision to organize a settlement of their own at the Bay of Quinte. Anoghsoktea

(Isaac Hill) and Kanonraron (Aaron Hill) elected to join Brant on the Grand, but their stay was short-lived. Within four years,

following lengthy and bitter disputes with the strong-willed Brant, they returned crestfallen and repentant, much to Deserontyon’s

grim satisfaction. Meanwhile Haldimand, though still aiming at uniting the two communities into one settlement, had none the

less assisted Deserontyon. He arranged the purchase from the Mississaugas of a 12 by 13 mile tract fronting on the bay and

transferred it to the Fort Hunter Mohawks. The transaction was made official on 1 April 1793, when after repeated requests

from Deserontyon Lieutenant Governor Simcoe formally authorized the grant of the tract to its residents. Contrary to Deserontyon’s

wishes, however, the right to dispose of the land as they saw fit was not bestowed. Like other Six Nations leaders, Deserontyon

was compensated by Britain for losses suffered during the war. Having left behind in New York 82 acres of cultivated land,

a barn, house and furniture, sleigh, carriage, wagon, and various farm animals, he received a lump sum of $1100, yearly presents,

and an annual pension of $70, together with an assurance that his son Peter John would be properly educated at a boarding-school.

In recognition of his services to the Indian Department he was also given 3,000 acres of land. Deserontyon was active on behalf

of the educational and spiritual welfare of his Mohawks. In response to his entreaties, a teacher named Vincent, who would

also double as a catechist, was appointed to the settlement in 1785 on the understanding that his salary would be paid by

the Indian Department. This move and the visits paid by John Stuart, formerly the Anglican missionary at Fort Hunter, were

received with great joy by Deserontyon and his fellow Indians. Official assistance was also offered to the little community,

which in 1788 numbered about a hundred, with the construction of the necessary schoolhouse and church. The latter edifice,

when finally completed late in 1791 through the exertions of the Mohawks themselves and with the aid of a small grant from

the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, was graced with some of the communion silver that Deserontyon had recovered

in 1783 from the chapel at Fort Hunter. All these developments augured well for the settlement, particularly when Vincent

was recruited to assist Stuart, now the parish clergyman at Cataraqui (Kingston), in the translation into Mohawk of the Gospel

of St Matthew. In 1789, however, with the work apparently unfinished, Vincent was dismissed and his place taken by an Indian

teacher named Peter. Although the latter’s credentials were deemed sound enough, he turned out to be an alcoholic and

had to be let go in turn, a state of affairs that was said to have thrown the community into confusion. In 1791 John Norton

was appointed, but he shortly quit the post on the grounds that the work was too confining and the Indians too demanding.

The problem of providing adequate instruction for Indian youth was not, it would appear, satisfactorily resolved in Deserontyon’s

lifetime. Although the authorities ultimately swallowed their objections to the chief’s decision to stay at the Bay

of Quinte and appreciated his offer of aid in 1794 when another Anglo-American war threatened, his leader-ship was not without

controversy. He annoyed Haldimand and the Indian Department in 1784 by trying to provide for the local Mississaugas when supplies

were distributed to the Mohawks as loyalists. Moreover, the factionalism endemic among the Six Nations also proved a serious

problem at the Bay of Quinte settlement. Following the Hills’ return from the Grand River, disputes reminiscent of those

that had disrupted Brant’s domain broke out. The source of the trouble is not clear. Deserontyon claimed that Isaac

Hill refused to attend council meetings and had set up his own council, and that members of Hill’s faction had opened

public houses, the sign over one being a picture of the devil. Hill alleged that Deserontyon had inflated his expenses for

the trip he made to Albany with Brant in 1797 to obtain compensation for lands the Mohawks had lost. The struggle culminated

in the killing by Hill’s party of two of Deserontyon’s relatives and in the intervention of William Claus, the

acting deputy superintendent general of Indian affairs in Upper Canada. Claus summoned a council in September 1800 to air

and, if possible to resolve the differences between the warring groups. Only after Hill publicly agreed to exclude himself

from the settlement’s affairs did an adamant Deserontyon agree to shake hands and permit the dangerous episode to close.

But Deserontyon’s problems did not end there. The closing years of his life were troubled by the so-called timber war

brought on when white lumbermen encroached on Indian lands. Although the depredations were condemned by both Deserontyon and

John Ferguson, a local Indian Department official, the chief was accused by his enemies of serving as a paid broker for white

timber interests while purportedly acting for the Indians. He strongly denied the charge, but the issue was still unresolved

when he died on 7 Jan. 1811. Like Joseph Brant, Deserontyon had been educated in a school run by whites and was considerably

acculturated to their customs. Nevertheless, he was described by Daniel Claus as “the clearest & best speaker of the

6 Nations according to the old way.” He was also an accomplished warrior and chief. His career illustrates the role

played by the Six Nations as Britain’s allies during the American revolution. It also serves to illuminate the problems

encountered by the Indian loyalists in the new province of Upper Canada. The town of Deseronto is named in his honour. From:

historical accounts & records

|