|

BRAVEHORSE WARRIOR Iroquet

Algonkin Warrior

Chief Iroquet

Warrior Citation

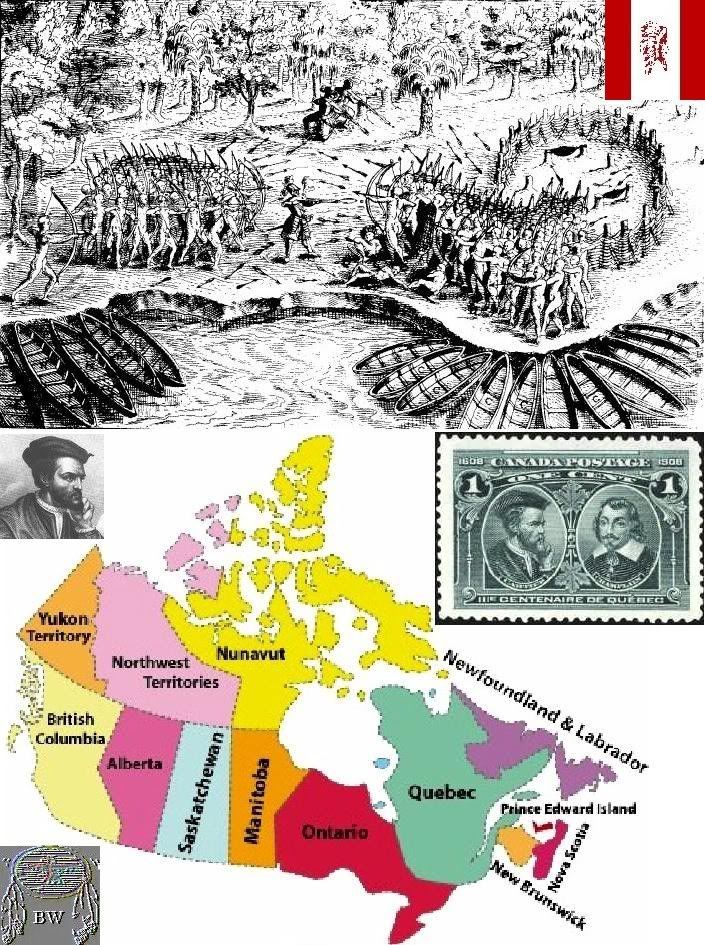

IROQUET (Yroquet), Algonkin chief; fl. 1609–15. Iroquet was the first Algonkin chief to meet Champlain in June 1609

near Quebec, where he had come with Outchetaguin, a Huron chief, to seek an alliance with the French in making war against

the Iroquois. Champlain agreed to join them, and his first attack on the Iroquois on Lake Champlain took place a few days

later. Champlain then agreed to meet with Iroquet and Outchetaguin at the mouth of the River of the Iroquois (Richelieu) the

following year, thus initiating the historic diplomatic and trading alliance between the Huron and Algonkin Native Americans

and the French. Iroquet and Outchetaguin arrived too late in 1610, however, to take part in Champlain’s second attack

on the Iroquois, but a three-day council was held by them with Champlain on Île de Saint-Ignace. Champlain requested that

Iroquet take a young French lad [possibly Étienne Brûlé] to winter at his home 80 leagues above the Rapids (Lachine) so that

he might learn his people’s language, observe the various tribes, and explore their water-ways and mines. Iroquet agreed,

but his followers feared the consequences if harm came to the boy. Champlain, however, won their consent by accepting a young

Huron lad, Savignon, to return to France with him. The following year, 1611, Iroquet and Outchetaguin, according to plan,

were met by Champlain in the St. Lawrence with a salvo of arquebuses, muskets, and small pieces, also two salutes from 13

pinnaces that had arrived for the trade. All this badly frightened the Native Americans, most of whom had never seen a European.

Champlain traded with them at length at the Rapids, at the same time learning of the geography of the country. Although uneasy

about many of the other French traders, the Native Americans reiterated their trust in Champlain, promising to show him their

country. Champlain in turn promised to request the king to send a small army to go to their country with him; he also promised

to establish a settlement there. Champlain was entirely satisfied with Iroquet’s treatment of the French boy, and this

year a second boy, attached to the trader Boyer or Bouvier, was allowed to return with the Algonkins. Champlain specified

that he must reside with Iroquet only.

Chief Iroquet

Warrior Citation

IROQUET (Yroquet), Algonkin chief; fl. 1609–15. Iroquet was the first Algonkin chief to meet Champlain in June 1609

near Quebec, where he had come with Outchetaguin, a Huron chief, to seek an alliance with the French in making war against

the Iroquois. Champlain agreed to join them, and his first attack on the Iroquois on Lake Champlain took place a few days

later. Champlain then agreed to meet with Iroquet and Outchetaguin at the mouth of the River of the Iroquois (Richelieu) the

following year, thus initiating the historic diplomatic and trading alliance between the Huron and Algonkin Native Americans

and the French. Iroquet and Outchetaguin arrived too late in 1610, however, to take part in Champlain’s second attack

on the Iroquois, but a three-day council was held by them with Champlain on Île de Saint-Ignace. Champlain requested that

Iroquet take a young French lad [possibly Étienne Brûlé] to winter at his home 80 leagues above the Rapids (Lachine) so that

he might learn his people’s language, observe the various tribes, and explore their water-ways and mines. Iroquet agreed,

but his followers feared the consequences if harm came to the boy. Champlain, however, won their consent by accepting a young

Huron lad, Savignon, to return to France with him. The following year, 1611, Iroquet and Outchetaguin, according to plan,

were met by Champlain in the St. Lawrence with a salvo of arquebuses, muskets, and small pieces, also two salutes from 13

pinnaces that had arrived for the trade. All this badly frightened the Native Americans, most of whom had never seen a European.

Champlain traded with them at length at the Rapids, at the same time learning of the geography of the country. Although uneasy

about many of the other French traders, the Native Americans reiterated their trust in Champlain, promising to show him their

country. Champlain in turn promised to request the king to send a small army to go to their country with him; he also promised

to establish a settlement there. Champlain was entirely satisfied with Iroquet’s treatment of the French boy, and this

year a second boy, attached to the trader Boyer or Bouvier, was allowed to return with the Algonkins. Champlain specified

that he must reside with Iroquet only.

In 1615 the promises of 1611 were fulfilled when Champlain travelled to the Huron country with a band of French soldiers.

Iroquet was the war-chief of the Algonkins in the Huron-Algonkin war-party against the Iroquois, which Champlain led from

the Huron country bordering Georgian Bay to the Iroquois country that lay south of Lake Ontario. After returning from the

raid, Iroquet and his Algonkins wintered near the Huron village of Cahiagué (near present-day Hawkestone, Ontario). Animosity

developed between the two communities as a result of Iroquet’s treatment of a captive whom the Hurons had handed over

to him for the customary torture. Iroquet treated the captive, who was a good hunter and an intelligent man, with fatherly

kindness. In resentment at this behaviour the Hurons appointed one of their men to kill the captive. In reprisal, the Algonkins

killed the slayer; whereupon the Hurons, further insulted by the death of one of their own people, attacked the Algon Native

Americans kins, and Iroquet was wounded by two arrow shots. In order to secure peace, the Algonkins were required to give

to the Hurons “fifty wampum belts with one hundred fathoms of the same,” also a great number of kettles and hatchets,

and two women captives. But the situation remained hazardous for the Algonkins, and, in Champlain’s opinion, these unsettled

affairs among the natives were perilous for the French residents of the district and could bring ruin to the trade. Two inhabitants

of Cahiagué sought out Champlain, who was some distance away, to beg him to attempt a reconciliation. He agreed, but first

visited a settlement of Nipissing Indians with whom he had planned to make a voyage of discovery to the north. To his profound

regret he found that Iroquet had already been there, and with gifts of wampum had secured the promise of the Nipissings to

postpone the voyage. Iroquet’s action in this matter may have been a precautionary move against Champlain’s making

alliances for trade with other nations; or it may have been born of fear for the safety of his relatively small band who were

faced with danger from the populous village of Cahiagué which at that time, Champlain states, consisted of some 200 long-houses.

In 1623–24 Sagard records that an Native American named Iroquet, who was well known in those areas, had been to the

Neutral country with 20 of his men, hunting for beaver, of which they had taken “fully five hundred.” He could

not be induced, however, to divulge to the French the route from the St. Lawrence to the Neutral country that bordered Lake

Erie. Thus did the Algonkins and Hurons guard jealously the furs that were basic to the economy of New France at that period.

As was customary, the tribe of Iroquet was often known by the name of its chief. In 1644 the Iroquets were described by Father

Barthélemy Vimont as “extremely insolent, arrogant, full of superstitions and very profligate,” whereas their

chief at that time said that they were “a remnant of one of the most flourishing tribes that ever dwelt in this country.”

From: historical accounts & records

In 1615 the promises of 1611 were fulfilled when Champlain travelled to the Huron country with a band of French soldiers.

Iroquet was the war-chief of the Algonkins in the Huron-Algonkin war-party against the Iroquois, which Champlain led from

the Huron country bordering Georgian Bay to the Iroquois country that lay south of Lake Ontario. After returning from the

raid, Iroquet and his Algonkins wintered near the Huron village of Cahiagué (near present-day Hawkestone, Ontario). Animosity

developed between the two communities as a result of Iroquet’s treatment of a captive whom the Hurons had handed over

to him for the customary torture. Iroquet treated the captive, who was a good hunter and an intelligent man, with fatherly

kindness. In resentment at this behaviour the Hurons appointed one of their men to kill the captive. In reprisal, the Algonkins

killed the slayer; whereupon the Hurons, further insulted by the death of one of their own people, attacked the Algon Native

Americans kins, and Iroquet was wounded by two arrow shots. In order to secure peace, the Algonkins were required to give

to the Hurons “fifty wampum belts with one hundred fathoms of the same,” also a great number of kettles and hatchets,

and two women captives. But the situation remained hazardous for the Algonkins, and, in Champlain’s opinion, these unsettled

affairs among the natives were perilous for the French residents of the district and could bring ruin to the trade. Two inhabitants

of Cahiagué sought out Champlain, who was some distance away, to beg him to attempt a reconciliation. He agreed, but first

visited a settlement of Nipissing Indians with whom he had planned to make a voyage of discovery to the north. To his profound

regret he found that Iroquet had already been there, and with gifts of wampum had secured the promise of the Nipissings to

postpone the voyage. Iroquet’s action in this matter may have been a precautionary move against Champlain’s making

alliances for trade with other nations; or it may have been born of fear for the safety of his relatively small band who were

faced with danger from the populous village of Cahiagué which at that time, Champlain states, consisted of some 200 long-houses.

In 1623–24 Sagard records that an Native American named Iroquet, who was well known in those areas, had been to the

Neutral country with 20 of his men, hunting for beaver, of which they had taken “fully five hundred.” He could

not be induced, however, to divulge to the French the route from the St. Lawrence to the Neutral country that bordered Lake

Erie. Thus did the Algonkins and Hurons guard jealously the furs that were basic to the economy of New France at that period.

As was customary, the tribe of Iroquet was often known by the name of its chief. In 1644 the Iroquets were described by Father

Barthélemy Vimont as “extremely insolent, arrogant, full of superstitions and very profligate,” whereas their

chief at that time said that they were “a remnant of one of the most flourishing tribes that ever dwelt in this country.”

From: historical accounts & records

|