|

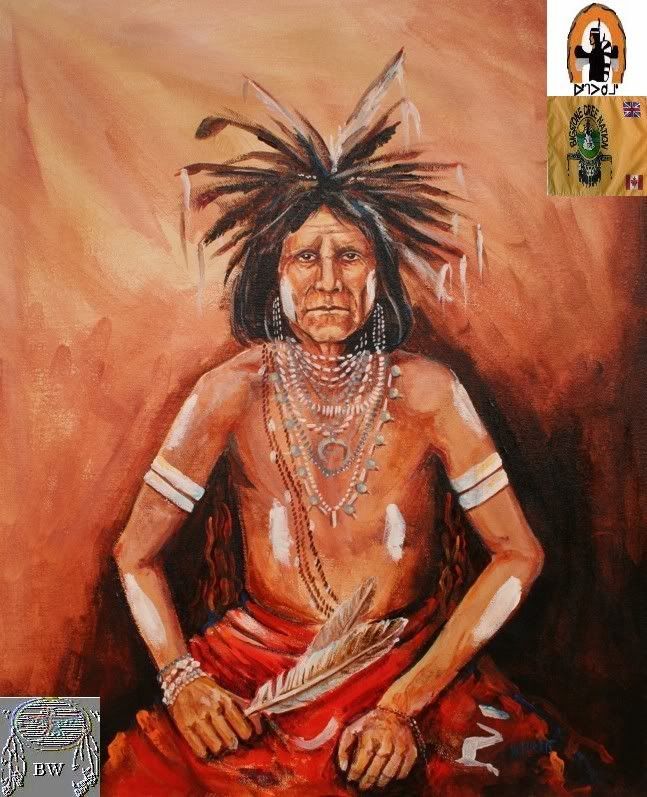

BRAVEHORSE WARRIOR Kupeyakwuskonam

Willow Cree Warrior

Chief One Arrow

Warrior Citation

KÜPEYAKWÜSKONAM (Kah-pah-yak-as-to-cum, One Arrow, known in French as Une Flèche), chief of a band of Willow Crees, b. c.

1815 probably in or near the valley of the Saskatchewan River; d. 25 April 1886 at St Boniface, Man. One Arrow was the chief

of a band of Willow Crees which, until the disappearance of the buffalo from the Canadian prairies in the 1870s, traditionally

hunted in the region bisected by the South Saskatchewan River and stretching from near Duck Lake in the north to Little Manitou

Lake and Goose Lake to the southeast and southwest respectively. After a last desperate trek to the Cypress Hills in search

of bison in 1879, the great majority of the band settled permanently on their reserve four miles east of the South Saskatchewan

River, behind the Métis settlement of Batoche (Sask.). After the 16-square-mile site was surveyed in 1881, the hunting operations

of the band appear to have shifted to the east, into the wooded and parkland areas of the Carrot River valley where small

game could still be found. One Arrow’s followers did not initially impress the officials of the Department of Native

American Affairs with their efforts towards agricultural self-sufficiency, but the department also took little notice of the

fact that, as late as 1884, the band had not received from the government many of the implements and some of the livestock

which it had been promised in 1876 under the terms of Treaty no.6. Nor did it receive, until 1884, the instruction and supervision

in farming given to most other bands; once it was begun, the band made rapid progress.

Chief One Arrow

Warrior Citation

KÜPEYAKWÜSKONAM (Kah-pah-yak-as-to-cum, One Arrow, known in French as Une Flèche), chief of a band of Willow Crees, b. c.

1815 probably in or near the valley of the Saskatchewan River; d. 25 April 1886 at St Boniface, Man. One Arrow was the chief

of a band of Willow Crees which, until the disappearance of the buffalo from the Canadian prairies in the 1870s, traditionally

hunted in the region bisected by the South Saskatchewan River and stretching from near Duck Lake in the north to Little Manitou

Lake and Goose Lake to the southeast and southwest respectively. After a last desperate trek to the Cypress Hills in search

of bison in 1879, the great majority of the band settled permanently on their reserve four miles east of the South Saskatchewan

River, behind the Métis settlement of Batoche (Sask.). After the 16-square-mile site was surveyed in 1881, the hunting operations

of the band appear to have shifted to the east, into the wooded and parkland areas of the Carrot River valley where small

game could still be found. One Arrow’s followers did not initially impress the officials of the Department of Native

American Affairs with their efforts towards agricultural self-sufficiency, but the department also took little notice of the

fact that, as late as 1884, the band had not received from the government many of the implements and some of the livestock

which it had been promised in 1876 under the terms of Treaty no.6. Nor did it receive, until 1884, the instruction and supervision

in farming given to most other bands; once it was begun, the band made rapid progress.

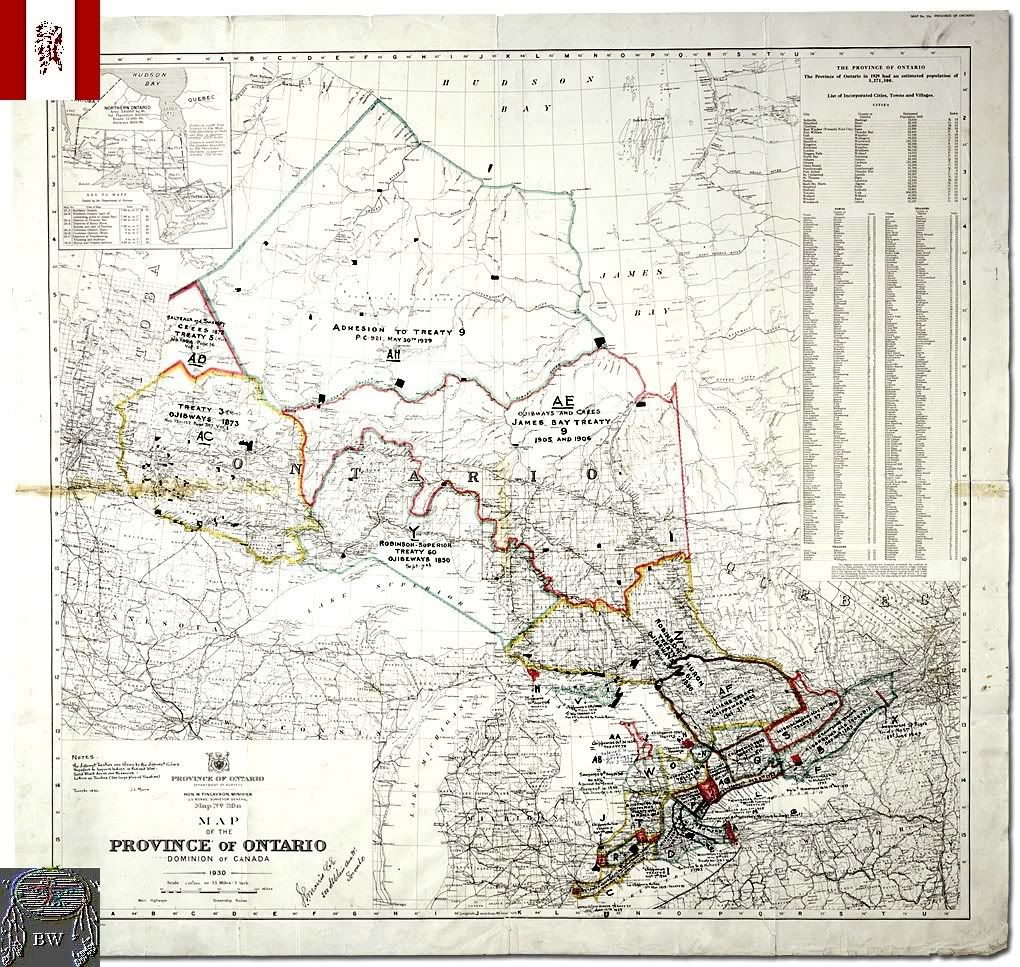

Chief One Arrow himself did not come into prominence until the outbreak in 1885 of the North-West rebellion. In 1876

he had been associated with chiefs Beardy [Kamðyistowesit] and Saswaypew (Cut Nose) in an attempt to obstruct the negotiation

of Treaty no.6 at Fort Carlton (Sask.), but on 28 August, five days after the treaty had been concluded, One Arrow and the

other two chiefs signed a formal adhesion to the agreement. In 1880 the same three chiefs were arrested on a charge of inciting

their followers to butcher government cattle. A jury refused to convict them, however, much to the disgust of the officials

of the Department of Indian Affairs. Four years later, in August 1884, One Arrow attended a large council of chiefs along

with Big Bear [Mistahimaskwa] and Papewes (Papaway, Lucky Man) to discuss Indian grievances. He seems to have joined in the

charges that the “sweet promises” made at the time of the treaty, “in order to get their country from them,”

had not been kept, and in the threats of unspecified but non-violent measures that would be taken in order to force the government

to act. In all of these activities, however, One Arrow does not seem to have played more than a minor role. His part in the

North-West rebellion is, in many respects, unclear. Since his reserve was the closest to the Métis settlement on the South

Saskatchewan River, his Native Americans were, naturally, most susceptible to Métis influence. On 17 March 1885 Métis leader

Gabriel Dumont visited the band and invited them to a meeting two days later. On 18 March, Indian Agent John Bean Lash arrived

and obtained a profuse profession of loyalty from the chief. As he left the reserve Lash was taken prisoner by Louis Riel

and an armed mob of about 40 Métis in one of the first overt acts of the rebellion. One Arrow and his band probably had no

part in the capture but the following day, under the guidance of their Métis farm instructor, Michel Dumas, One Arrow’s

men butchered all of their cattle and joined the rebels, apparently becoming the first Native American band to do so. The

chief and his men were subsequently seen by the captive Indian agent, Lash, and others, armed and in the company of Riel and

his Métis, immediately following the battle at Duck Lake on 26 March and in and around the settlement of Batoche until its

capture on 12 May. In fact, One Arrow appears to have been too old and feeble to have taken an active part in the hostilities.

As early as 1882 he had attempted to resign his chieftainship on grounds of old age and infirmity, but had been dissuaded

from doing so by an official of the Department of Native American Affairs. Nevertheless, One Arrow was arrested on a charge

of treason-felony, and tried at Regina on 13 Aug. 1885. The old man was utterly confused by the entire proceedings. His lawyer

confessed that he was unable to gain One Arrow’s confidence, and thus could not present a coherent defence. The sole

defence witness called to testify to the chief’s good character did not appear, and the greater part of the prosecution’s

evidence was not translated into Cree for the benefit of the prisoner, who spoke no English. Only after a verdict of guilty

had been rendered did One Arrow speak. He denied that he had actively participated in the rebellion, and explained that he

had been coerced by Gabriel Dumont into leaving his reserve and joining the rebels at Batoche. He claimed that he had shot

no one and had never had any intention of doing so. His explanations were to no avail, and he was sentenced to three years

in the Stony Mountain Penitentiary in Manitoba. In prison his health rapidly deteriorated and on 10 April 1886, after serving

only a little more than seven months of his sentence, he was released. Such was his condition, however, that he was unable

to proceed to his home, or even to walk. During his incarceration his conversion to Roman Catholicism brought him to the attention

of the archbishop of St Boniface, Alexandre-Antonin Taché, and upon his release One Arrow was carried to the archbishop’s

palace, where he lingered between life and death for a fortnight before expiring on Easter Sunday, 25 April 1886. During his

imprisonment the Department of Native American Affairs had unsuccessfully attempted to starve the members of his band into

abandoning their reserve and moving to Duck Lake, where they would be under closer supervision from the Native American agent

and other officials. Among One Arrow’s last acts was a plea to Native American Commissioner Edgar Dewdney against the

mistreatment of the members of his band. One Arrow was not an extraordinary chief. He did not take a leading role in the movement

to promote the settlement of the claims and grievances of the Native Americans of the northwest against the Canadian government,

but few doubted his support for that movement. Although he was one of only three chiefs from the northwest imprisoned for

his part in the rebellion of 1885, his ambiguous and ineffective actions in concert with the Métis seem hardly to have been

sufficient to justify his conviction. Indeed, during the entire affair and its aftermath, he gave the appearance of a tragic

old man, destroyed by forces over which he had no control and which he could not understand. From: historical accounts & records

Chief One Arrow himself did not come into prominence until the outbreak in 1885 of the North-West rebellion. In 1876

he had been associated with chiefs Beardy [Kamðyistowesit] and Saswaypew (Cut Nose) in an attempt to obstruct the negotiation

of Treaty no.6 at Fort Carlton (Sask.), but on 28 August, five days after the treaty had been concluded, One Arrow and the

other two chiefs signed a formal adhesion to the agreement. In 1880 the same three chiefs were arrested on a charge of inciting

their followers to butcher government cattle. A jury refused to convict them, however, much to the disgust of the officials

of the Department of Indian Affairs. Four years later, in August 1884, One Arrow attended a large council of chiefs along

with Big Bear [Mistahimaskwa] and Papewes (Papaway, Lucky Man) to discuss Indian grievances. He seems to have joined in the

charges that the “sweet promises” made at the time of the treaty, “in order to get their country from them,”

had not been kept, and in the threats of unspecified but non-violent measures that would be taken in order to force the government

to act. In all of these activities, however, One Arrow does not seem to have played more than a minor role. His part in the

North-West rebellion is, in many respects, unclear. Since his reserve was the closest to the Métis settlement on the South

Saskatchewan River, his Native Americans were, naturally, most susceptible to Métis influence. On 17 March 1885 Métis leader

Gabriel Dumont visited the band and invited them to a meeting two days later. On 18 March, Indian Agent John Bean Lash arrived

and obtained a profuse profession of loyalty from the chief. As he left the reserve Lash was taken prisoner by Louis Riel

and an armed mob of about 40 Métis in one of the first overt acts of the rebellion. One Arrow and his band probably had no

part in the capture but the following day, under the guidance of their Métis farm instructor, Michel Dumas, One Arrow’s

men butchered all of their cattle and joined the rebels, apparently becoming the first Native American band to do so. The

chief and his men were subsequently seen by the captive Indian agent, Lash, and others, armed and in the company of Riel and

his Métis, immediately following the battle at Duck Lake on 26 March and in and around the settlement of Batoche until its

capture on 12 May. In fact, One Arrow appears to have been too old and feeble to have taken an active part in the hostilities.

As early as 1882 he had attempted to resign his chieftainship on grounds of old age and infirmity, but had been dissuaded

from doing so by an official of the Department of Native American Affairs. Nevertheless, One Arrow was arrested on a charge

of treason-felony, and tried at Regina on 13 Aug. 1885. The old man was utterly confused by the entire proceedings. His lawyer

confessed that he was unable to gain One Arrow’s confidence, and thus could not present a coherent defence. The sole

defence witness called to testify to the chief’s good character did not appear, and the greater part of the prosecution’s

evidence was not translated into Cree for the benefit of the prisoner, who spoke no English. Only after a verdict of guilty

had been rendered did One Arrow speak. He denied that he had actively participated in the rebellion, and explained that he

had been coerced by Gabriel Dumont into leaving his reserve and joining the rebels at Batoche. He claimed that he had shot

no one and had never had any intention of doing so. His explanations were to no avail, and he was sentenced to three years

in the Stony Mountain Penitentiary in Manitoba. In prison his health rapidly deteriorated and on 10 April 1886, after serving

only a little more than seven months of his sentence, he was released. Such was his condition, however, that he was unable

to proceed to his home, or even to walk. During his incarceration his conversion to Roman Catholicism brought him to the attention

of the archbishop of St Boniface, Alexandre-Antonin Taché, and upon his release One Arrow was carried to the archbishop’s

palace, where he lingered between life and death for a fortnight before expiring on Easter Sunday, 25 April 1886. During his

imprisonment the Department of Native American Affairs had unsuccessfully attempted to starve the members of his band into

abandoning their reserve and moving to Duck Lake, where they would be under closer supervision from the Native American agent

and other officials. Among One Arrow’s last acts was a plea to Native American Commissioner Edgar Dewdney against the

mistreatment of the members of his band. One Arrow was not an extraordinary chief. He did not take a leading role in the movement

to promote the settlement of the claims and grievances of the Native Americans of the northwest against the Canadian government,

but few doubted his support for that movement. Although he was one of only three chiefs from the northwest imprisoned for

his part in the rebellion of 1885, his ambiguous and ineffective actions in concert with the Métis seem hardly to have been

sufficient to justify his conviction. Indeed, during the entire affair and its aftermath, he gave the appearance of a tragic

old man, destroyed by forces over which he had no control and which he could not understand. From: historical accounts & records

|