|

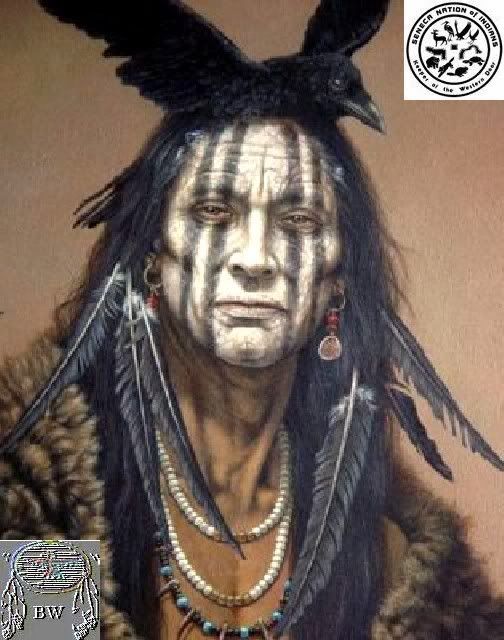

BRAVEHORSE WARRIOR Kaghswaghtaniunt

Seneca Warrior

Chief Kaghswaghtaniunt

Warrior Citation

KAGHSWAGHTANIUNT (Coswentannea, Gaghswaghtaniunt, Kachshwuchdanionty, Tohaswuchdoniunty, Belt of Wampum, Old Belt, Le Collier

Pendu, White Thunder), a Seneca Indian living on the upper Ohio River by 1750; d. c. 1762. As Cadsedan-hiunt he was identified

in 1750 as one of the “Chiefs of the Seneca Nations settled at Ohio”; as Kachshwuchdanionty, he appeared in 1753

as one of “the Chiefs now entrusted with the Conduct of Publick affairs among the Six Nations” on the Ohio; and

in 1755 he was described as “Belt of Wampum or White Thunder [who] keeps the wampum.” His English and French designations

apparently attempt to translate his Seneca name; compare Zeisberger’s form, gaschwechtonni, of the Onondaga word meaning

to make a belt of wampum. Kaghswaghtaniunt was closely associated with Tanaghrisson from 1749 to 1754, during the rising conflict

between English and French over the Ohio country. In 1753 he was one of the delegations that confronted Paul Marin de La Malgue

at Fort de la Rivière au Bœuf (Waterford, Pa.) with a protest against the French military advance toward the Ohio. Suffering

some hurt, Kaghswaghtaniunt made the return trip to Logstown (Chiningué, now Ambridge, Pa.) by canoe, arriving in mid-January

1754. He was accompanied by Tanaghrisson and a French party under Michel Maray de La Chauvignerie. Soon afterward he was accused

by an associate, Jeskakake, of conspiring to betray the French officer to the English. Kaghswaghtaniunt was among the 80 to

100 Mingos who later in 1754 joined Lieutenant-Colonel George Washington near present Uniontown, Pa., on his march toward

Fort Duquesne (Pittsburgh, Pa.). With Washington’s defeat by Louis Coulon de Villiers, the group of Mingos took refuge

at Aughwick (Shirleysburg, Pa.). Kaghswaghtaniunt was one of the Indians who joined Major-General Edward Braddock’s

campaign against Fort Duquesne in 1755 and after the British defeat retired to the vicinity of Harris’s Ferry (Harrisburg,

Pa.).

Chief Kaghswaghtaniunt

Warrior Citation

KAGHSWAGHTANIUNT (Coswentannea, Gaghswaghtaniunt, Kachshwuchdanionty, Tohaswuchdoniunty, Belt of Wampum, Old Belt, Le Collier

Pendu, White Thunder), a Seneca Indian living on the upper Ohio River by 1750; d. c. 1762. As Cadsedan-hiunt he was identified

in 1750 as one of the “Chiefs of the Seneca Nations settled at Ohio”; as Kachshwuchdanionty, he appeared in 1753

as one of “the Chiefs now entrusted with the Conduct of Publick affairs among the Six Nations” on the Ohio; and

in 1755 he was described as “Belt of Wampum or White Thunder [who] keeps the wampum.” His English and French designations

apparently attempt to translate his Seneca name; compare Zeisberger’s form, gaschwechtonni, of the Onondaga word meaning

to make a belt of wampum. Kaghswaghtaniunt was closely associated with Tanaghrisson from 1749 to 1754, during the rising conflict

between English and French over the Ohio country. In 1753 he was one of the delegations that confronted Paul Marin de La Malgue

at Fort de la Rivière au Bœuf (Waterford, Pa.) with a protest against the French military advance toward the Ohio. Suffering

some hurt, Kaghswaghtaniunt made the return trip to Logstown (Chiningué, now Ambridge, Pa.) by canoe, arriving in mid-January

1754. He was accompanied by Tanaghrisson and a French party under Michel Maray de La Chauvignerie. Soon afterward he was accused

by an associate, Jeskakake, of conspiring to betray the French officer to the English. Kaghswaghtaniunt was among the 80 to

100 Mingos who later in 1754 joined Lieutenant-Colonel George Washington near present Uniontown, Pa., on his march toward

Fort Duquesne (Pittsburgh, Pa.). With Washington’s defeat by Louis Coulon de Villiers, the group of Mingos took refuge

at Aughwick (Shirleysburg, Pa.). Kaghswaghtaniunt was one of the Indians who joined Major-General Edward Braddock’s

campaign against Fort Duquesne in 1755 and after the British defeat retired to the vicinity of Harris’s Ferry (Harrisburg,

Pa.).

After Tanaghrisson’s death in October 1754, Scarroyady had succeeded him as “half king” or spokesman

for the Iroquois of the Ohio; but Scarroyady’s absences in New York left the leadership unsettled, and in January 1756

Kaghswaghtaniunt and another Seneca, the White Mingo, were reported to be at odds about the succession to Tanaghrisson. Later

in 1756 the Mingo refugees moved from Pennsylvania to New York under the protection of Sir William Johnson, the superintendent

of Indian affairs. In June of that year Johnson sent Kaghswaghtaniunt with a message to the Senecas, and advised him and his

family to settle among them. The western (Geneseo) division of the tribe, encouraged by Louis-Thomas Chabert de Joncaire and

his sons, had traditionally been favourable to the French, but Kaghswaghtaniunt continued to attend Johnson’s councils

and in April 1759 announced to him the Geneseo decision (said to have been made the previous winter) to take the British side.

He was one of the Seneca chiefs who conferred with Johnson at Oswego (Chouaguen) in August 1759 after the British capture

of Fort Niagara (near Youngstown, N.Y.); a year later he headed a party that with 600 other Iroquois accompanied Major-General

Jeffery Amherst’s army to Montreal, which fell on 8 Sept. 1760. In 1761 Donald Campbell a commandant of Detroit sent

Johnson word of Seneca activity against the English in the west. When Kaghswaghtaniunt met Johnson at Niagara in August, however,

he assured Johnson that “he was invested with the direction of the affairs of the nation where he lived” and that

“all [was] well and very peaceable.” Kaghswaghtaniunt visited Fort Niagara again during the winter, and William

Walters, the commandant, wrote of him on 5 April 1762: “He is a good old fellow & I always Receive him Kindly and give

him a Little Ammunition & provision.” Not long after this, Kaghswaghtaniunt seems to have died. Not much is known of

his family. His wife and three grown daughters were with him at a council in Philadelphia in April 1756, and also at Fort

Johnson, New York, in November 1759. A stepson, Aroas or Silver Heels, prominent in his own right, appears in documents of

1755 and later. A reference to “the Old Belts Daughter” in June 1763 gives the impression that her father was

then dead, and in subsequent documents the daughters are identified as Silvers Heels’ sisters. From: historical accounts

& records

After Tanaghrisson’s death in October 1754, Scarroyady had succeeded him as “half king” or spokesman

for the Iroquois of the Ohio; but Scarroyady’s absences in New York left the leadership unsettled, and in January 1756

Kaghswaghtaniunt and another Seneca, the White Mingo, were reported to be at odds about the succession to Tanaghrisson. Later

in 1756 the Mingo refugees moved from Pennsylvania to New York under the protection of Sir William Johnson, the superintendent

of Indian affairs. In June of that year Johnson sent Kaghswaghtaniunt with a message to the Senecas, and advised him and his

family to settle among them. The western (Geneseo) division of the tribe, encouraged by Louis-Thomas Chabert de Joncaire and

his sons, had traditionally been favourable to the French, but Kaghswaghtaniunt continued to attend Johnson’s councils

and in April 1759 announced to him the Geneseo decision (said to have been made the previous winter) to take the British side.

He was one of the Seneca chiefs who conferred with Johnson at Oswego (Chouaguen) in August 1759 after the British capture

of Fort Niagara (near Youngstown, N.Y.); a year later he headed a party that with 600 other Iroquois accompanied Major-General

Jeffery Amherst’s army to Montreal, which fell on 8 Sept. 1760. In 1761 Donald Campbell a commandant of Detroit sent

Johnson word of Seneca activity against the English in the west. When Kaghswaghtaniunt met Johnson at Niagara in August, however,

he assured Johnson that “he was invested with the direction of the affairs of the nation where he lived” and that

“all [was] well and very peaceable.” Kaghswaghtaniunt visited Fort Niagara again during the winter, and William

Walters, the commandant, wrote of him on 5 April 1762: “He is a good old fellow & I always Receive him Kindly and give

him a Little Ammunition & provision.” Not long after this, Kaghswaghtaniunt seems to have died. Not much is known of

his family. His wife and three grown daughters were with him at a council in Philadelphia in April 1756, and also at Fort

Johnson, New York, in November 1759. A stepson, Aroas or Silver Heels, prominent in his own right, appears in documents of

1755 and later. A reference to “the Old Belts Daughter” in June 1763 gives the impression that her father was

then dead, and in subsequent documents the daughters are identified as Silvers Heels’ sisters. From: historical accounts

& records

|