|

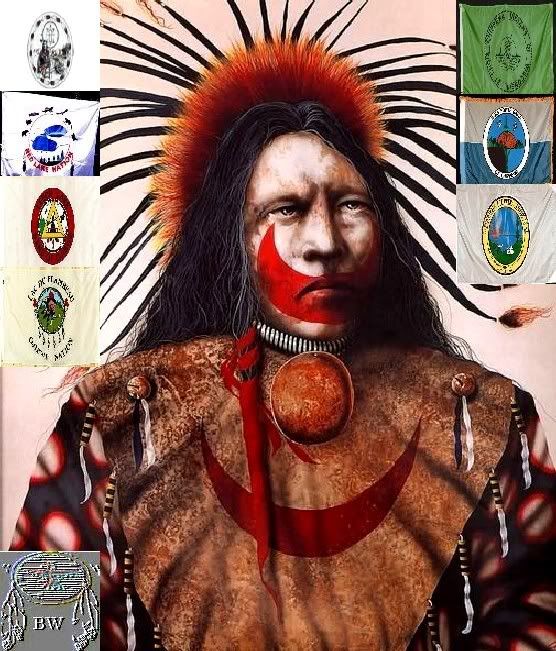

BRAVEHORSE WARRIOR Peguis

Saulteaux Ojibwa Warrior

Chief Peguis

Warrior Citation

PEGUIS, (Be-gou-ais, Be-gwa-is, Pegeois, Pegouisse, Pegowis, Pegqas, Pigewis, Pigwys; also known as the Destroyer and Little

Chip, and baptized William King), Saulteaux Indian chief; b. c. 1774 near Sault Ste Marie (Ont.); d. 28 Sept. 1864 at Red

River. Born in the Great Lakes area, Peguis was among the Saulteaux, or Ojibwa, who migrated west with the fur trade in the

late 1790s, settling on Netley Creek, a branch of the Red River south of Lake Winnipeg. He welcomed the first settlers brought

to the Red River area by Lord Selkirk [Douglas] in 1812 and is given credit for aiding and defending them during their difficult

years. When the main group of settlers arrived in 1814 to find none of the promised gardens planted or houses built, Peguis

guided them to Fort Daer (Pembina, N.D.) to hunt buffalo. The children, weak from the journey, were carried on ponies provided

by the Native Americans. The Saulteaux showed the settlers how to hunt and brought them along on their annual trek to buffalo

country. Peguis sided with the Hudson’s Bay Company during its dispute with the North West Company, and after the Selkirk

settlers had been attacked at Seven Oaks on 19 June 1816 (Robert Semple) he offered assistance to the survivors. The future

grandmother of Louis Riel, the first white woman resident in the West, Marie-Anne Gaboury, whose husband was away when the

Nor’Westers occupied Fort Douglas, was rescued by Peguis, and she and her children were kept safely in his camp for

several weeks. Before the other settlers fled north to Norway House, they were befriended and fed by Peguis. On 18 July 1817

Peguis was one of five Saulteaux and Cree chiefs who signed a treaty with Lord Selkirk to provide an area for settlement purposes.

This included a strip of land two miles wide on each side of the Red and Assiniboine rivers, beginning at their confluence

within the present city of Winnipeg and extending up the Red to what is now Grand Forks (N.D.) and up the Assiniboine to Rat

Creek. Plots of land reaching six miles in each direction from Fort Douglas, Fort Daer, and Grand Forks were also included.

In exchange, each tribe was to receive annual payments of 100 lbs of tobacco. This land treaty was the first to be signed

in western Canada. Colin Inkster, a Manitoba politician, writing in 1909 remembered Peguis as “short in stature, with

a strong, well-knit frame, and the voice of an orator.” He was “clad in a cotton shirt, breech clout, red cloth

leggings and over all a blanket wrapped loosely about him, his hair hung in two long plaits studded with brass ornaments,

his breast decorated with medals.” One of the latter was a medal presented to him by Lord Selkirk as a confirmation

of the agreement of 1817. Peguis’ appearance, however, was disfigured as part of his nose had been bitten off during

a tribal quarrel in about 1802. As a result, he was known to some settlers as “The Cut-Nosed Chief.” Peguis and

his followers, who in 1816 numbered 65 men, lived by raising corn, potatoes, barley, and other grain at their village on Netley

Creek, as well as by hunting. Peguis was met at this village by Anglican missionary John West in 1820 and later he supported

missionary work among his followers [William Cockran].

Chief Peguis

Warrior Citation

PEGUIS, (Be-gou-ais, Be-gwa-is, Pegeois, Pegouisse, Pegowis, Pegqas, Pigewis, Pigwys; also known as the Destroyer and Little

Chip, and baptized William King), Saulteaux Indian chief; b. c. 1774 near Sault Ste Marie (Ont.); d. 28 Sept. 1864 at Red

River. Born in the Great Lakes area, Peguis was among the Saulteaux, or Ojibwa, who migrated west with the fur trade in the

late 1790s, settling on Netley Creek, a branch of the Red River south of Lake Winnipeg. He welcomed the first settlers brought

to the Red River area by Lord Selkirk [Douglas] in 1812 and is given credit for aiding and defending them during their difficult

years. When the main group of settlers arrived in 1814 to find none of the promised gardens planted or houses built, Peguis

guided them to Fort Daer (Pembina, N.D.) to hunt buffalo. The children, weak from the journey, were carried on ponies provided

by the Native Americans. The Saulteaux showed the settlers how to hunt and brought them along on their annual trek to buffalo

country. Peguis sided with the Hudson’s Bay Company during its dispute with the North West Company, and after the Selkirk

settlers had been attacked at Seven Oaks on 19 June 1816 (Robert Semple) he offered assistance to the survivors. The future

grandmother of Louis Riel, the first white woman resident in the West, Marie-Anne Gaboury, whose husband was away when the

Nor’Westers occupied Fort Douglas, was rescued by Peguis, and she and her children were kept safely in his camp for

several weeks. Before the other settlers fled north to Norway House, they were befriended and fed by Peguis. On 18 July 1817

Peguis was one of five Saulteaux and Cree chiefs who signed a treaty with Lord Selkirk to provide an area for settlement purposes.

This included a strip of land two miles wide on each side of the Red and Assiniboine rivers, beginning at their confluence

within the present city of Winnipeg and extending up the Red to what is now Grand Forks (N.D.) and up the Assiniboine to Rat

Creek. Plots of land reaching six miles in each direction from Fort Douglas, Fort Daer, and Grand Forks were also included.

In exchange, each tribe was to receive annual payments of 100 lbs of tobacco. This land treaty was the first to be signed

in western Canada. Colin Inkster, a Manitoba politician, writing in 1909 remembered Peguis as “short in stature, with

a strong, well-knit frame, and the voice of an orator.” He was “clad in a cotton shirt, breech clout, red cloth

leggings and over all a blanket wrapped loosely about him, his hair hung in two long plaits studded with brass ornaments,

his breast decorated with medals.” One of the latter was a medal presented to him by Lord Selkirk as a confirmation

of the agreement of 1817. Peguis’ appearance, however, was disfigured as part of his nose had been bitten off during

a tribal quarrel in about 1802. As a result, he was known to some settlers as “The Cut-Nosed Chief.” Peguis and

his followers, who in 1816 numbered 65 men, lived by raising corn, potatoes, barley, and other grain at their village on Netley

Creek, as well as by hunting. Peguis was met at this village by Anglican missionary John West in 1820 and later he supported

missionary work among his followers [William Cockran].

In 1836 St Peter’s mission was built nearby to serve the Christian Native Americans, and on 7 Oct. 1840 Peguis gave

up three of his four wives so that he could be baptized by the Reverend John Smithurst. He and his remaining wife took the

names William and Victoria King, and their children later adopted the surname of Prince. Peguis was recognized and honored

by the HBC throughout his life, and in 1835 Governor George Simpson gave him an annuity of $8 a year in recognition of his

contributions. Peguis also carried with him a testimonial from Lord Selkirk which stated that he was “one of the principal

chiefs of the Chipeways, or Saulteaux of Red River, has been a steady friend of the settlement ever since its first establishment,

and has never deserted its cause in its greatest reverses.” Peguis was a welcome visitor to the Red River Settlement

and, even after the threat of native hostilities had passed, his earlier support was remembered. However, in 1860 Peguis became

dissatisfied with the white settlers when they began using lands not surrendered by his tribe, and he made a formal protest

to the Aborigines’ Protection Society. He also stated that the tobacco payment instituted in 1817 had been simply a

goodwill token and that arrangements for the formal surrender of the land had never taken place. In addition, he questioned

the right of the governor and Council of Assiniboia to make any laws which affected the unsurrendered area until after a further

treaty was made. No action was taken by the authorities to rectify the situation until after the area was transferred to the

Dominion of Canada in 1870; then Treaty No.1 was negotiated by Peguis’ son, Mis-koo-kee-new, known as Red Eagle or Henry

Prince, in August 1871. Peguis did not live to see the treaty; he died in September 1864, and was buried in the graveyard

of St Peter’s Church. In 1924 a monument honouring the chief was erected in Kildonan Park, Winnipeg. From: historical

accounts & records

In 1836 St Peter’s mission was built nearby to serve the Christian Native Americans, and on 7 Oct. 1840 Peguis gave

up three of his four wives so that he could be baptized by the Reverend John Smithurst. He and his remaining wife took the

names William and Victoria King, and their children later adopted the surname of Prince. Peguis was recognized and honored

by the HBC throughout his life, and in 1835 Governor George Simpson gave him an annuity of $8 a year in recognition of his

contributions. Peguis also carried with him a testimonial from Lord Selkirk which stated that he was “one of the principal

chiefs of the Chipeways, or Saulteaux of Red River, has been a steady friend of the settlement ever since its first establishment,

and has never deserted its cause in its greatest reverses.” Peguis was a welcome visitor to the Red River Settlement

and, even after the threat of native hostilities had passed, his earlier support was remembered. However, in 1860 Peguis became

dissatisfied with the white settlers when they began using lands not surrendered by his tribe, and he made a formal protest

to the Aborigines’ Protection Society. He also stated that the tobacco payment instituted in 1817 had been simply a

goodwill token and that arrangements for the formal surrender of the land had never taken place. In addition, he questioned

the right of the governor and Council of Assiniboia to make any laws which affected the unsurrendered area until after a further

treaty was made. No action was taken by the authorities to rectify the situation until after the area was transferred to the

Dominion of Canada in 1870; then Treaty No.1 was negotiated by Peguis’ son, Mis-koo-kee-new, known as Red Eagle or Henry

Prince, in August 1871. Peguis did not live to see the treaty; he died in September 1864, and was buried in the graveyard

of St Peter’s Church. In 1924 a monument honouring the chief was erected in Kildonan Park, Winnipeg. From: historical

accounts & records

|